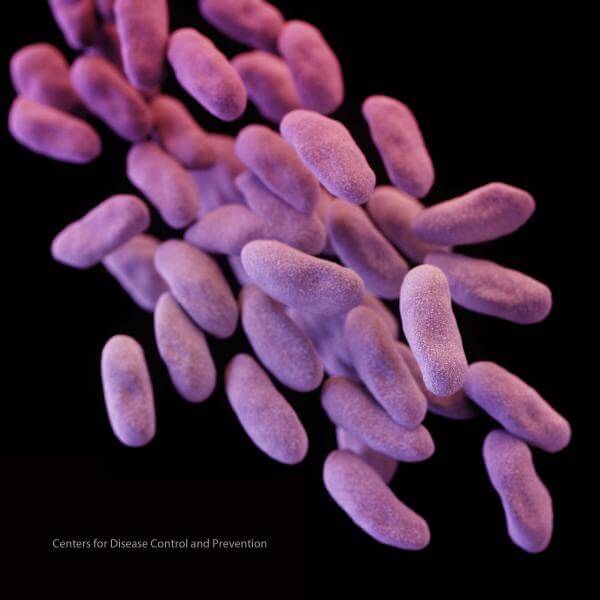

In the clearest picture yet of the burden of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the United States—an important cause of healthcare-associated infections—a group from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday reported low overall incidence but regional variation, with most cases linked to earlier hospitalization and discharge to long-term care.

In 2013, the CDC sounded an alarm about CRE, thought to be more dangerous than methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). CRE are resistant to nearly all antibiotics, have high mortality rates in invasive infections, and can spread their resistance genes to other bacteria in the body.

Echoing the CDC’s 2013 warning, the researchers who published the latest surveillance findings say the low levels suggest the time is now to take action. The findings appeared yesterday in an early online edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

Some geographic variation

The investigators based their findings on CRE surveillance in 2012 and 2013 from cities in seven US states that take part in the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program: Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Oregon.

Of 599 CRE cases from 481 people, 520 (87%) were isolated from urine samples and 68 (11%) from blood. Patients’ median age was 66, and the overall annual CRE incidence was 2.93 per 100,000 population. The authors found that the level is much lower than for other healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). For comparison, the level for MRSA was 25.1 per 100,000 and for Clostridium difficile it was 147.2 per 100,000.

Most cases occurred in people who had been hospitalized or had indwelling medical devices. CRE infections were fatal for 51 people (9%), including more than a quarter of those who had the organism isolated from a normally sterile site.

Researchers found some geographic variation in CRE levels, with an incidence ratio higher than predicted in Georgia, Maryland, and New York, and lower than thought in Colorado, New Mexico, and Oregon.

Differences by region underscore the need to better understand the local epidemiology and tailor prevention efforts, the group wrote. “The frequency with which individuals with CRE are transferred between facilities emphasizes the need for regional control efforts in all the facilities,” they added.

The investigators also repeated the CDC’s earlier warning, that the CRE levels they found show an emerging threat that can be turned back now with control interventions.

Surveillance data crucial

In an editorial on the study in the same issue of JAMA, Mary Hayden, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, wrote that surveillance information is a critical step toward controlling CRE, and that the findings contain good news and bad news.

She said the bad news is that CRE were identified in every region, with incidence rates in some regions suggesting that they might be endemic. Hayden added, however, that even in the highest region, Georgia, the crude incidence rate is still relatively low, suggesting that steps taken now to control CRE could have “a sizeable effect.”

Expanding CRE surveillance to more regions, including rural areas and metropolitan areas known to have higher incidence, could provide a more complete picture of the disease burden in the United States, she wrote. She added, though, that it’s unclear if Congress will pass a budget request to improve national surveillance efforts.