Nitrogen pollution threats to endangered species in the U.S. are widespread, but solutions are out there.

A new study by researchers affiliated with UC Santa Cruz and published online in the journal BioScience looks at how nitrogen affects threatened biodiversity across the United States.

“Nitrogen pollution is a prevalent atmospheric and biogeochemical global change driver, with growing effects on terrestrial, aquatic, and coastal ecosystems,” the researchers write in “Nitrogen Pollution Is Linked to U.S. Listed Species Declines.”

“It starts in the air and water,” said co-author Erika Zavaleta, Pepper-Giberson Chair in Environmental Studies at UC Santa Cruz. “On land, nitrogen pollution ultimately ends up in the soil,” she said. “It’s essentially fertilizers coming out of air and water,” from smokestacks and auto tailpipes.

The authors surveyed 1,400 species listed under the Endangered Species Act, finding 78 that face known hazards from excess nitrogen. The mechanisms of nitrogen’s impacts are diverse, encompassing direct toxicity, depleted oxygen resulting from excess fertilization, and incursions by invasive species that outcompete local populations or exclude their food sources.

Researchers included lead author Daniel Hernández who now teaches at Carleton College in Minnesota. Hernández, who worked as a post-doctoral researcher at UCSC in 2007-2008, will teach in the UCSC Doris Duke Conservation Scholars Program this summer. Other UCSC affiliated authors include EPA scientist Dena Vallano, a former UCSC post doc, Zdravka Tzankova, assistant professor in environmental studies, Corinne Morozumi, environmental studies alumna, and Jae Pasari, Ph.D. in environmental studies, 2011.

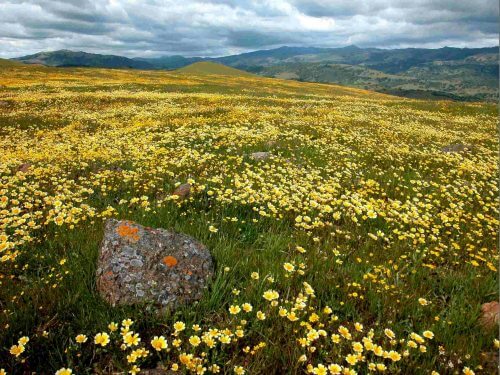

To zoom in on the problem in our area, the team looked at grasslands growing in serpentine outcroppings in fault areas of the East Bay and southern Santa Clara County where there are “rare and endemic plant and animal species you can’t find any other place in the world,” Zavaleta said.

Researchers looked at how nitrogen has accumulated over the last 150 years. They studied tree rings and used greenhouse experiments to see how adding more nitrogen affected rare plants that support a threatened butterfly, the Edith’s Bay checkerspot.

Nitrogen pollution is a challenging problem to address because it is very diffuse, coming from many different sources. “It’s a policy challenge and a conservation challenge,” Zavaleta said.

One challenge is that regulations have not kept pace with the steady growth of nitrogen pollution. Fertilizer use, leguminous crop agriculture, and fossil fuel burning have more than doubled the amount of global reactive nitrogen, and in the United States, human-derived nitrogen additions are thought to be fourfold greater than natural sources.

Despite this trend, “existing laws and policies to protect biodiversity were largely developed before these threats were fully recognized,” the authors state.

If regulatory structures can be appropriately modernized, efforts to mitigate nitrogen’s effects on endangered species may be fruitful, the authors write, because unlike global threats that resist local solutions, nitrogen pollution “can be more readily addressed within the boundaries of a single nation, region, or watershed.”

The study was funded by a grant from the Kearney Foundation for Soil Science.

Mr. Chester, this article is about reactive nitrogen species, mostly formed through human activities, and not the inert gas of which you speak.

Nitrogen accounts for 78% of our breathable atmosphere. It is not a pollutant but a fact of life. Please stop spreading false information about how it pollutes.