A patch made from cryopreserved human umbilical cord may be a novel method for treating spina bifida in utero, according to researchers at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). The findings were published today in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the journal of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

A patch comprised of the donated outer layer of the umbilical cord from healthy newborns was used for the repairs. The surgeries were performed at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital.

“The promise of this patch is that the umbilical cord contains specific natural material called heavy chain hyaluronic acid/pentraxin3 that has regenerative properties,” said Ramesha Papanna, M.D., M.P.H., lead author, assistant professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at McGovern Medical School and maternal-fetal medicine specialist at The Fetal Center at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital. “It allows the local tissue to grow in at the repair site instead of a healing by scar formation that occurs with traditional repair methods. This decrease in scar formation may help improve the spinal cord function further and reduce the need for future surgeries to remove the effects of the scar tissue on the spinal cord.”

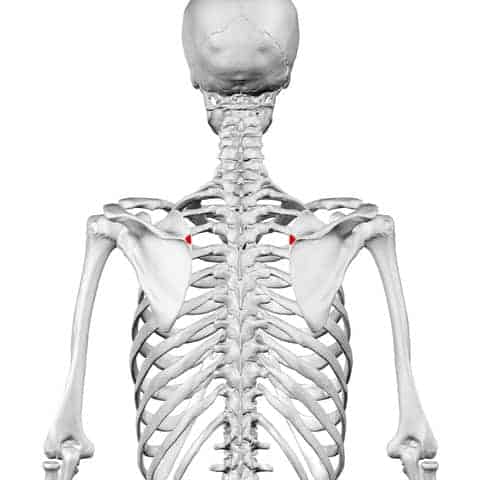

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, spina bifida is characterized by the incomplete development of the coverings of the brain, spinal cord or meninges – the protective covering around the brain or spinal cord. It is the most common neural tube defect in the country, affecting 1,500 to 2,000 of the more than 4 million babies born each year. The defect can result in paralysis, urinary or bowel dysfunction and mental retardation.

In 2011, a landmark clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health found that if a fetus underwent in utero surgery to close the defect, the serious complications associated with spina bifida could be reversed or lessened. In cases where the defect was too large to close with the fetus’ existing skin, a patch was necessary. But in some cases, scar tissue may cause adherence of the patch to the underlying spinal cord. This could result in a loss of neurologic function as the child ages. Further surgery was often needed to remove this scar tissue.

“The use of this patch for fetal repair heralds a new era for fetal spina bifida repair,” said Kenneth Moise, M.D., co-author, professor, director of the Fetal Intervention Fellowship Program at McGovern Medical School and co-director of The Fetal Center. “For the first time, a bioscaffold has been successfully employed to allow the fetus to heal itself. The implications for the future of a minimally invasive approach to fetal spina bifida repair and even neonatal spina bifida repair are enormous.”

In the first case study, the skin lesion in the fetus measured 5 centimeters by 6 centimeters and there was evidence of Chiari II malformation, a complication of spina bifida in which the brain stem and the cerebellum protrude into the spinal canal or neck area. It can lead to problems with feeding, swallowing or breathing control.

At 24 weeks gestation, the patient underwent fetal surgery by KuoJen Tsao, M.D., associate professor and The Children’s Fund Distinguished Professor in Pediatric Surgery and co-director of The Fetal Center, and Stephen Fletcher, D.O., co-author, associate professor in McGovern Medical School’s Department of Pediatric Surgery and pediatric neurosurgeon affiliated with Memorial Hermann Mischer Neuroscience Institute at the Texas Medical Center and Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital. Moise and Papanna participated in the surgery.

The lesion was closed with skin edges sutured to the human umbilical cord patch in a watertight fashion. The mother was discharged on postoperative day 5. The baby was born at 37 ½ weeks and the patch was intact with no leakage of fluid. The patch at the site of the lesion appeared semi-translucent with incomplete regeneration of the skin. Within two weeks, the skin had healed over the patch spontaneously. The child had normal movements of the lower extremities and bladder control function and there was a complete reversal of the Chiari II malformation.

In the second case, performed by the same team, the patient’s fetus had a lesion of 4 centimeters by 5 centimeters and Chiari II malformation. The expectant mother underwent surgery at 25 weeks gestation and the procedure and application of the patch were similar to the first case. The baby was delivered at 37 1/2 weeks and there was complete covering of the lesion with the patch but without skin grown into the patch. As with the first case, the skin grew over the patch and by day 30, was completely healed. There was normal motor and urinary function and the Chiari II malformation was completely reversed.

Both cases were approved by the FDA under Expanded Access use, the Fetal Therapy Board of The Fetal Center at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital and UTHealth Institutional Review Board prior to the surgery.

The clinical cases were the culmination of seven years of research after Papanna, and co-author Lovepreet K. Mann, M.B.B.S., instructor in McGovern Medical School’s Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, began brainstorming ideas about possible patch materials. This led them to co-author Scheffer C.G. Tseng, M.D., Ph.D., of Ocular Surface Center and TissueTech, Inc., in Miami, Fla., who was using human amniotic membrane and umbilical cord – donated by mothers of healthy infants – to repair corneas. The patch is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for corneal repair.

“This patch acts as a scaffold, which is watertight and allows native tissue to regenerate in an organized manner, and has anti-scarring, anti-inflammatory properties. Preventing the scarring could prevent tethering, which can prevent further damage to the cord,” Mann said.

The patch was first tested in animal models by a team of researchers that included Papanna, Mann, Moise, Fletcher and Saul Snowise, M.D., a maternal-fetal fellow who has now joined McGovern Medical School as an assistant professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences.

In 2011, after the landmark national trial for fetal surgery was ended early because of positive results, physicians at McGovern Medical School and The Fetal Center were the first in Texas to perform the newly approved surgery. Since then the team has performed more than 30 fetal surgeries to treat spina bifida.

Mann said the team was taken aback at first by the lack of skin covering the patch at the birth of the first infant but she could see the child’s legs moving and knew it was an early success that they hope will continue as the baby grows. “It would mean a lot to the team if we can make a small change and improve the quality of life for the child. That will mean we really did something,” she said.

The team has since completed a third surgery and Fletcher has used the new patch in surgeries to untether the spinal cord of children who had previous spina bifida surgery. They wait now to see if the umbilical cord patch will help prevent tethering in the long run.

Currently, the team members are working on finding ways to make the skin heal inside the uterus and different ways to deploy the patch over the defect site through less-invasive ways.

Research collaborators, who come from different disciplines across the country, include Sanjay Prabhu, M.B.B.S., assistant professor of pediatric neuroradiology at Harvard Medical School; Raymond Grill, Ph.D., professor of neurobiology and anatomical sciences at the University of Mississippi; and Russell Stewart, Ph.D., professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Utah.