Liquid methane-filled canyons hundreds of meters deep with walls as steep as ski slopes etch the surface of Titan, researchers report in a new study. The new findings provide the first direct evidence of these features on Saturn’s largest moon, and could give scientists insights into Titan’s origins and similar geologic processes on Earth, according to the study’s authors.

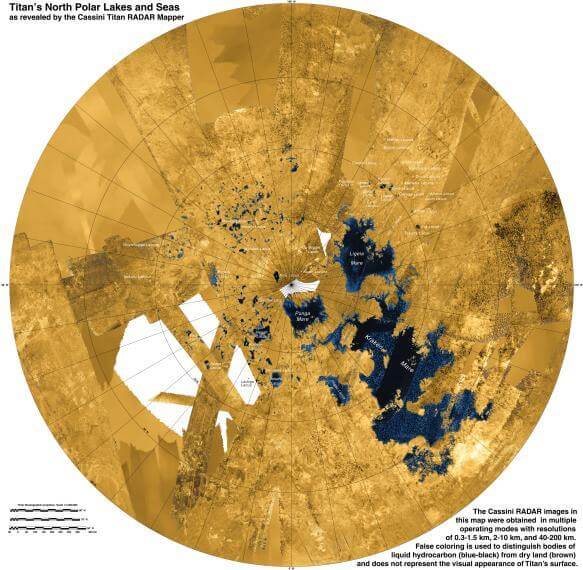

New Cassini radar observations of Titan’s north pole depict cavernous gorges a little less than a kilome-ter (less than half a mile) wide with walls up to 570 meters (1870 feet) tall — about 30 meters (98 feet) higher than New York’s Freedom Tower. The eight canyons branch off from Vid Flumina, a more than 400-kilometer (249-mile) long river flowing into Titan’s second-largest sea, Ligeia Mare. The new data confirm the canyons are filled with flowing methane — a feature researchers had suspected but not directly observed, according to the study’s authors.

The new findings suggest the canyons were likely carved by liquid methane draining into Vid Flumina, a process similar to the carving of river gorges on Earth, according to the study’s authors. The new re-search could help scientists better understand these geological processes, they said.

“These are processes we need to totally understand because they can shed deeper light on our own planet,” said Valerio Poggiali, a planetary scientist at the La Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, and lead author of the new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, launched in 1997, has granted scientists their first up-close look at Saturn, its rings and moons. Cassini’s observations of Titan — with its many Earth-like features — have given sci-entists a glimpse of what our planet might have been like millions of years ago, according to NASA.

Scientists first observed Titan’s hydrocarbon seas in 2006 during one of Cassini’s early flybys. Six years later the spacecraft spied Vid Flumina and its branching channels. Researchers suspected those chan-nels, some of which appeared canyon-like, were filled with flowing methane. Other clues like icy peb-bles rounded by river-flow affirmed their suspicions, but they lacked direct evidence the channels were liquid-filled – until now.

“What we didn’t know was whether some channels still contained liquids, i.e., whether these rivers of methane were still flowing,” said Rosaly Lopes, a planetary geologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Labora-tory in Pasadena, California, who is also mapping Titan’s surface but was not connected to the study. “[Poggiali’s] work is what nailed that.”

Methane rivers and seas

The researchers used Cassini’s instruments to bounce radio signals off Titan’s surface. The returned signals defined the moon’s surface features, allowing the researchers to discern rocky outcrops from smooth liquid.

The signals show the canyons’ walls rise at least as sharply as 40 degrees. Earth shares a similar slope in one of its most dangerous ski runs: Corbet’s Coulier in Wyoming. On Earth, skiers plunge down the lofty mountain and glide over snow, but a skier on Titan would tumble hundreds of meters down the canyon walls and splash into a methane river. Although the images showed the canyons were filled with liquid methane, they could not measure the depth of the liquid, which could run shallow or deep, according to the new study.

The study’s authors draw comparisons between Titan’s canyons, and Arizona and Utah’s Lake Powell and the Nile River gorge. Both feature canyons and valleys etched by erosion from flowing liquid. The deep cuts in Titan’s landscape indicate the process that created them occurred over multiple extended periods, though the age of that process remains uncertain. They could have been created by uplift of the terrain or changes in sea level, or both, according to the study’s authors.

Titan is the only planetary body in our solar system, other than Earth, to have a surface actively eroding on a large scale, according to Lopes.

“We have seen some canyons elsewhere, such as Vallis Marineris on Mars,” Lopes said. “However, on Titan, this study shows evidence that some canyons are still filled with liquid and presumably in the process of carving canyons.”

Studying the geologic processes on Titan can help researchers tease apart the moon’s origins and con-ditions on early Earth. Titan allows scientists to see how these processes change under varying condi-tions, like changes in temperature, according to Lopes.

“On Earth we can’t vary the conditions like surface temperature and atmospheric density to see how geologic processes would behave,” Lopes said. But by turning to Titan, scientists can see how familiar processes could change when those conditions are altered, she added.

“Although the term is overused, Titan is really a ‘natural laboratory’ for understanding geological pro-cesses,” Lopes said.

Lopes said many more small canyons may line Titan’s surface, possibly hidden just below the resolu-tion of Cassini’s instruments. Future missions could reveal those and other features, which may fur-ther color our understanding of Titan’s origins, she said.

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.