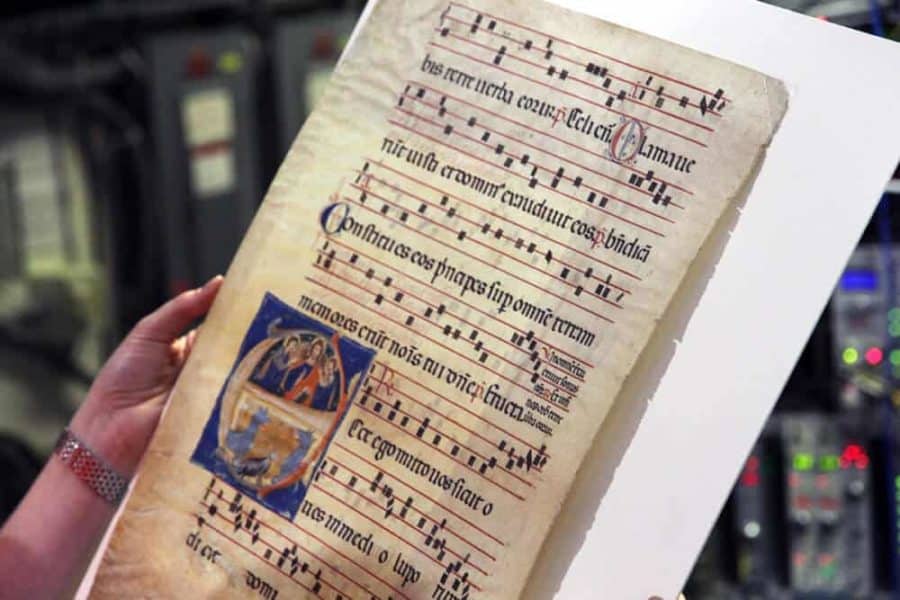

Analyzing pigments in medieval illuminated manuscript pages at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) is opening up some new areas of research bridging the arts and sciences.

Louisa Smieska and Ruth Mullett studied manuscript pages from Cornell University Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections (RMC), dating from the 13th to the 16th centuries, using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and spectral imaging analysis.

“Our initial goal was to learn more about Cornell’s fragments and about trends in pigment use,” said Mullett, a medieval studies doctoral student. “An initial survey using a portable point XRF [p-XRF] instrument uncovered several things we weren’t expecting.”

Their research, published June 23 in the journal Applied Physics A, was co-authored by Laurent Ferri, RMC’s curator of pre-1800 collections, and CHESS scientist Arthur Woll.

XRF measures X-rays emitted by atoms to probe the chemical elements present in an object. The p-XRF survey found interesting mineral impurities in a common blue pigment made from the copper mineral azurite. The team then selected seven of the most interesting fragments to study, using the more powerful facilities at CHESS.

“We weren’t expecting to learn anything from the trace elements in azurite,” Mullett said. “We weren’t really interested in azurite at all; we were hoping to uncover how many of our leaves used lapis lazuli, the other blue pigment.”

The team was surprised to find the trace element barium present in the azurite blues in many of the leaves. “We called it ‘the barium question,’” said Smieska, a former postdoc at CHESS. “At first it took a little while to convince everybody why I was so excited that barium was present and why it could be significant. Then we saw the maps and started seeing why; barium was there in every azurite blue we studied.”

Identifying which trace elements are present and in what amounts can give a unique fingerprint to a pigment, which may help link scattered pages in different collections. The impurities and trace elements are also potentially significant indicators of where the pigments originated, and can aid in other historic and scientific inquiries.

Smieska, M.S. ’12, Ph.D. ’15, took on the project as a postdoctoral researcher at CHESS after completing her doctorate in chemistry.

How it evolved – and how the medievalist, the curator and the scientists came together – is a story of Cornell connections, hinging (mostly) on Mellon courses at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art.

Smieska first discovered Cornell had illuminated manuscripts thanks to Mullett’s final project in the Mellon Curatorial Practicum they took in spring 2014. She met Woll in the Art|Science Intersections course the following spring – “my introduction to the technique of XRF mapping,” she said.

This led her to work for Woll at CHESS last year and an XRF mapping workshop she led for researchers interested in cultural heritage. Ferri was among the participants. “He suggested that we examine the blue pigments in the illuminated manuscript fragments that it happened Ruth had been cataloging,” Smieska said.

They chose examples to study at CHESS “based on the range of geographical and historical time periods they represented and those that yielded unusual or surprising results in the p-XRF survey,” Mullett said. “We looked at the range of pigments on a particular leaf. We did comparative work on a historiated initial – one of the larger in-filled initials on a page – that had some blue in it, and smaller initials that had a different kind of blue pigment,” and examined fragments with “more than one blue or one red in a page.”

“The other feature we were looking for were pigments that seemed unusual. … We found a gray that we don’t believe has been previously attested to in the known pigment recipe books.”

Fragments until recently have received little scholarly attention but have much to offer manuscript studies, Mullett believes: “Research like ours may make it possible, for example, to narrow the geographic region of production by identifying unusual pigments in a palette.”

Pigment analysis can help in provenance research to link far-flung manuscript pages and even reconcile them to their original book sources. Other benefits for conservators, historians, geologists and others include “the potential to learn more about trade routes, historic mining sites, and the regional use of pigments and ingredients,” Mullett said.

Cornell’s collection of illuminated pages spans the 9th to the 16th centuries. Such fragments are flat and more conducive to imaging tools than complete volumes, Ferri said.

“Fragments are great because you can document or cover more topics, styles, techniques and periods with 50 fragments from different books, as opposed to one book made by a few people in one region over a few years,” he said. “That being said, it is important to have entire books as well.”

Mullett is a fellow in the Fragmentarium project based at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, which is building a database of fragments from different institutions.

“I hope to find new matches between fragments and good ways of testing the theory of our experimentation, and of confirming these leaves are all from the same place,” she said. “This has really turned into a brand new project for me. I’ve now developed a very keen interest in pigments and patterns in pigmentation that I didn’t have before.”

Smieska studied fine art as an undergraduate; she is now an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Scientific Research at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. “I didn’t realize there were scientists studying artwork until I was in grad school already,” she said. “I love working with the objects. The amazing thing is every piece of analysis I do, I look at the object and appreciate it more deeply. … It makes you respect the craftsmanship and the abilities of the people who made them.”

“I’d be really excited to see this project continue. There’s a potentially enormous sample set out there,” Smieska said.