t’s well known that exposure to extremely loud noises — an explosion, a firecracker or even a concert — can lead to permanent hearing loss. But knowing how to treat noise-induced hearing loss, which affects about 15 percent of Americans, has largely remained a mystery.

That may eventually change, thanks to new research from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, which sheds light on how noise-induced hearing loss happens and shows how a simple injection of a salt- or sugar-based solution into the middle ear may preserve hearing. The results of the study were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States.

Deafening sound

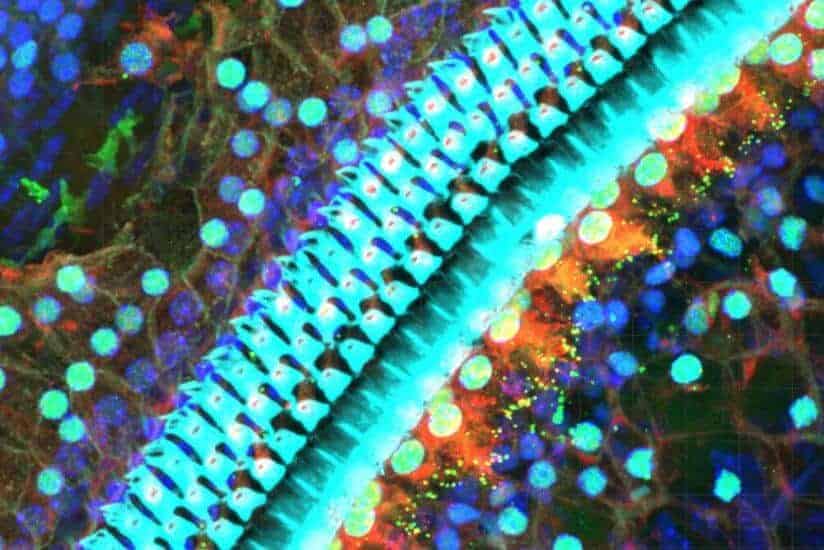

To develop a treatment for noise-induced hearing loss, the researchers first had to understand its mechanisms. They built a tool using novel miniature optics to image inside the cochlea, the hearing portion of the inner ear, and exposed mice to a loud noise similar to that of a roadside bomb.

They discovered that two things happen after exposure to a loud noise: sensory hair cells, which are the cells that detect sound and convert it to neural signals, die, and the inner ear fills with excess fluid, leading to the death of neurons.

“That buildup of fluid pressure in the inner ear is something you might notice if you go to a loud concert,” said the study’s corresponding author John Oghalai, chair and professor of the USC Tina and Rick Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery and holder of the Leon J. Tiber and David S. Alpert Chair in Medicine. “When you leave the concert, your ears might feel full and you might have ringing in your ears. We were able to see that this buildup of fluid correlates with neuron loss.”

Both neurons and sensory hair cells play critical roles in hearing.

“The death of sensory hair cells leads to hearing loss. But even if some sensory hair cells remain and still work, if they’re not connected to a neuron, then the brain won’t hear the sound,” Oghalai says.

The researchers found that sensory hair cell death occurred immediately after exposure to loud noise and was irreversible. Neuron damage, however, had a delayed onset, opening a window of opportunity for treatment.

Hearing loss caused by loud noises: a simple solution

The buildup of fluid in the inner ear occurred over a period of a few hours after loud noise exposure and contained high concentrations of potassium. To reverse the effects of the potassium and reduce the fluid buildup, salt- and sugar-based solutions were injected into the middle ear, just through the eardrum, three hours after noise exposure. The researchers found that treatment with these solutions prevented 45 to 64 percent of neuron loss, suggesting that the treatment may offer a way to preserve hearing function.

The treatment could have several potential applications, Oghalai explained.

“I can envision soldiers carrying a small bottle of this solution with them and using it to prevent hearing damage after exposure to blast pressure from a roadside bomb,” he said. “It might also have potential as a treatment for other diseases of the inner ear that are associated with fluid buildup, such as Ménière’s disease.”

Oghalai and his team plan to conduct further research on the exact sequence of steps between fluid buildup in the inner ear and neuron death, followed by clinical trials of their potential treatment for noise-induced hearing loss.