You won’t smell it. You won’t taste it. And you certainly won’t see it. But a nanocellulose material derived from all-natural substances could potentially become a food additive that reduces fat digestion and absorption and aids in weight loss.

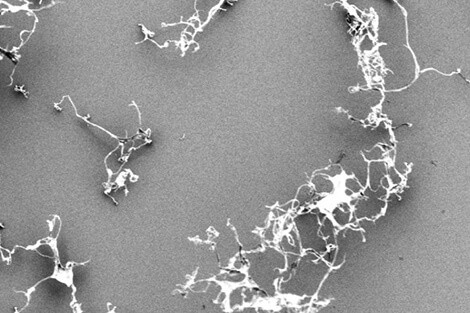

Cellulose is one of nature’s most abundant biopolymers, found in everything from cotton to vegetables. Researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health recently discovered that when cellulose is engineered into “spaghetti-looking fibers” that are a mere 50 nanometers in diameter—far thinner than a human hair—they have an uncanny ability to stop fat from being digested. In a new study published in ACS Nano, rats that were fed heavy cream containing nanocellulose absorbed 36% less fat than rats that were fed regular heavy cream. Similar experiments performed in a simulated gastrointestinal tract yielded even more dramatic results: nanocellulose cut fat absorption by 48%.

“It’s like having your cake and eating it too,” said Philip Demokritou, senior author of the study and director of the School’s Center for Nanotechnology and Nanotoxicology. What excites Demokritou most about the study isn’t necessarily that fat absorption was curbed, but that it was done so by a nanoscale material made of natural wood fibers and engineered using purely mechanical means. “There are no chemicals,” he said. “I’m a believer that we should learn more from nature and use more nature-inspired and derived materials. There’s 4 billion years of free R&D there, and instead we always look toward chemicals.”

A few years back, Demokritou’s team, along with colleagues from Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, began exploring how cellulose behaves in the gut when reduced to the nanoscale.

Their initial focus was on studying the ways in which nanocellulose interacts with biomolecules in the gut and whether it carries any toxicological risks. To find out, they began running nanocellulose mixed with different foods through a simulated gastrointestinal (GI) tract system they built in the lab. In most cases, when triglycerides—the major constituents of edible fats—are broken down in the small intestine by digestive enzymes, they release free fatty acids and monoacylglycerol, which can then be absorbed by the gut. But when food samples containing the nanocellulose made it to the small intestine, the researchers noticed that pH levels remained relatively constant, a sign that fewer fatty acids were being released. “It was an indication that fat globules were not being digested,” Demokritou said.

This accidental discovery was a lightbulb moment for Demokritou and his team. They soon were mixing small amounts of nanocellulose into heavy cream, mayonnaise, coconut oil, and corn oil and exposing gut cells to the foods, then moved on to feeding it to rats. The results varied by fat type, but in all cases fat digestion was slowed and reduced significantly. As for why that’s the case, the study showed that nanocellulose interferes with the actions of lipase and bile salts, which our bodies deploy to digest fats.

While still in the early stages of their research, the scientists said that the initial findings suggest that nanocellulose and other nature-derived biopolymers have promise as additives that could usher in a new class of functional foods, or foods that are enhanced to provide certain health benefits. Moreover, nanocellulose might prove helpful in fighting the obesity epidemic, said Glen DeLoid, research associate in the Department of Environmental Health and first author on the ACS Nano paper. “Obesity is a worldwide problem and huge challenge for the health care community. We’re hoping that nanocellulose might serve as an additional tool to diet and exercise,” he said.

The versatility of nanocellulose is such that it could be mixed directly into high-fat foods, DeLoid says, or encapsulated as a supplement that users take before a fatty meal. Before that, though, the team will continue probing the toxicological profile of nanocellulose to ensure its safety. One upside on that front is that regular cellulose is already widely used in foods and classified by the Food and Drug Administration as a GRAS material, or Generally Recognized As Safe.

Demokritou and colleagues are hopeful that their nanocellulose is just as innocuous as its larger counterpart. “I’m optimistic that there won’t be any toxicity associated with nanocellulose,” he says. “After all, it’s nature wisdom.”

Other co-authors of the study include Ikjot Singh Sohal, Laura R. Lorente, Ramon M. Molina, Georgios Pyrgiotakis, Ana Stevanovic, Ruojie Zhang, David Julian McClements, Nicholas K. Geitner, Douglas W. Bousfield, Kee Woei Ng, Say Chye Joachim Loo, David C. Bell, and Joseph Brain.