For the first time in decades, researchers have identified a new ‘micro-organ’ within the immune system – and they say it’s an important step towards understanding how to make better vaccines.

In a study published this week in Nature Communications, scientists at Australia’s Garvan Institute of Medical Research have identified where the immune system ‘remembers’ past infections and vaccinations – and where immune cells gather to mount a rapid response against an infection the body has seen before.

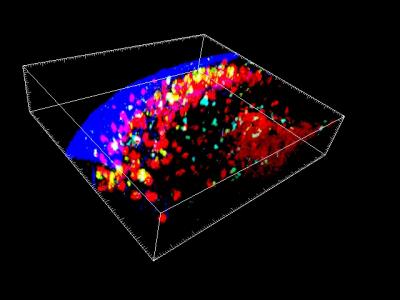

The structure was only discovered when the researchers ‘made movies’ of the immune system in action, using sophisticated high resolution 3D microscopy in living animals. Jam-packed with immune cells of many kinds, the structure is strategically positioned to detect infection early, making it a one-stop shop for fighting a ‘remembered’ infection – fast.

We have known for millennia that people exposed to an infection are often protected from getting the same infection again – ever since the Plague of Athens in 430 BC, where plague survivors were noted to have developed immunity against reinfection. Yet, major questions remain about how the body can fight back fast when it encounters an infection that it has been previously exposed to (through a vaccine or through an earlier infection).

A new structure that appears when it’s needed

The researchers reveal the existence of thin, flattened structures extending over the surface of lymph nodes in mice. These dynamic structures are not always present: instead, they appear only when needed to fight an infection against which the animal has previously been exposed.

Crucially, researchers also saw the structures – which they have named SPFs (or ‘subcapsular proliferative foci’) – inside sections of lymph nodes from patients, suggesting that they help fight reinfection in people as well as in mice.

Using sophisticated ‘two-photon’ in vivo microscopy, the researchers could see that several classes of immune cells gathered together in SPFs. Memory B cells, which carry information about how best to attack the infection, clustered there. So did other cell types that act as helpers.

Importantly, the researchers could also see that memory B cells were changing into infection-fighting plasma cells. This is a key step in the fight against infection, because plasma cells make antibodies to recognise and fend off the invader and protect the body from disease.

“It was exciting to see the memory B cells being activated and clustering in this new structure that had never been seen before,” says Garvan’s Dr Imogen Moran, the first author on the new study. “We could see them moving around, interacting with all these other immune cells and turning into plasma cells before our eyes.”

A need for speed

A/Prof Tri Phan (who led the research) says the SPF structures are perfectly placed to fight infection fast – so they can stop disease in its tracks before it takes hold.

“When you’re fighting bacteria that can double in number every 20 to 30 minutes, every moment matters. To put it bluntly, if your immune system takes too long to assemble the tools to fight the infection, you die,” he says.

“This is why vaccines are so important. Vaccination trains the immune system, so that it can make antibodies very rapidly when an infection reappears. Until now we didn’t know how and where this happened.

“Now, we’ve shown that memory B cells rapidly turn into large numbers of plasma cells in the SPF. The SPF is located strategically where bacteria would re-enter the body and it has all the ingredients assembled in one place to make antibodies – so it’s remarkably well engineered to fight reinfection fast.”

Hiding in plain sight

The researchers say no one had seen the structures before because traditional microscopy approaches look at thin 2D sections of tissue that been chemically ‘fixed’ to provide a snapshot in time. The SPF is thin, and it comes and goes: these are both attributes that make it hard to detect using a conventional approach.

“It was only when we did two-photon microscopy – which lets us look in three dimensions at immune cells moving in a living animal – that we were able to see these SPF structures forming,” says Dr Moran.

“So this is a structure that’s been there all along, but no one’s actually seen it yet, because they haven’t had the right tools. It’s a remarkable reminder that there are still mysteries hidden within the body – even though we scientists have been looking at the body’s tissues through the microscope for over 300 years,” says A/Prof Phan.

Hope for better vaccines

A/Prof Phan says the new discovery is an important step towards understanding how to make better vaccines.

“Up until now we have focussed on making vaccines that can generate memory B cells,” he says. “Our finding of this new structure suggests that we should now also focus on understanding how those memory B cells are reactivated to make plasma cells, so that we can make this process more efficient.”