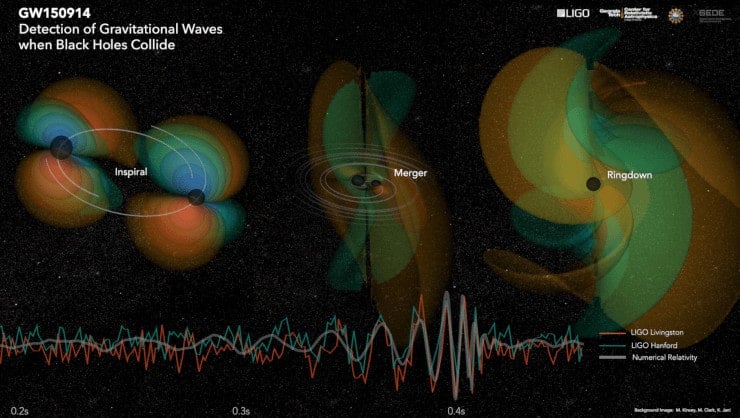

In February 2016, astronomers shook the scientific world with the announcement that they had observed gravitational waves from a cataclysmic event in the distant universe — the collision of two massive black holes, celestial objects so dense that not even light can escape from them.

Gravitational waves, hard-to-see ripples in the fabric of space-time, had been predicted by Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in 1915. These gravitational waves carry information about their origins, potentially offering a new way to observe the cosmos. Three years ago, however, researchers didn’t know if this first observation was merely an anomaly or part of a widespread phenomenon that could teach us about the population of black holes in the universe.

A dozen Georgia Tech faculty members, postdoctoral researchers, and students participated with hundreds of other researchers in the National Science Foundation-sponsored LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) Scientific Collaboration that reported the first gravitational waves. After the announcement, the work continued, and scientists from around the world have now observed 10 black hole collisions and a merger of two binary neutron stars using LIGO and the European-based Virgo gravitational wave detector.

Catalog of Coalescing Cosmic Objects

The records of these cataclysmic cosmic events, including four black hole observations disclosed for the first time, have been collected into a catalog released December 1 at the Gravitational Wave Physics and Astronomy Workshop held in College Park, Maryland. Production of the catalog suggests that gravitational wave astronomy will indeed offer astronomers a new way to view the secrets of the universe.

“The individual black hole detections previously announced allow us to confirm, after many years of searching, that gravitational wave astronomy is a feasible endeavor,” said James Alexander Clark, a research scientist in Georgia Tech’s Center for Relativistic Astrophysics (CRA) in the School of Physics and a member of the LIGO collaboration. “We now know that pairs of massive black holes exist and collide frequently enough for us to detect gravitational waves within a human lifetime. We also know that the instruments and analysis procedures we use are capable of detecting and characterizing gravitational wave sources and we have been able to start probing some basic features of the theory of general relativity.”

Astronomers do not have the luxury of repeating laboratory experiments to build confidence in their findings, Clark pointed out. “Instead, we rely on observing large samples of objects and phenomena spread throughout the universe. By building a ‘census’ of this population, we are rapidly learning more about how common these objects are, what their general properties are like, and about the diversity of black holes in the universe.”

Expanding the Observations

That census should expand more rapidly starting in April 2019 when LIGO begins its next observing run. The two instruments, one in Livingston, Louisiana, and the other in Hanford, Washington, are shut down periodically for upgrades to improve sensitivity. “By observing a larger sample of binary black hole sources, we are more likely to find systems with more extreme configurations that allow more stringent tests of our models — and of general relativity,” Clark added.

The new Gravitational Wave Catalog shows that gravitational waves from powerful cosmic phenomena arrive at the Earth almost once every 15 days of observation, noted Karan Jani, a postdoctoral fellow in the CRA and also a member of the LIGO collaboration. “Future releases will provide much stronger tests of Einstein’s theory of gravity, and help provide a better understanding of how black holes are formed in the universe.”

Data collected on the 10 black hole mergers describe objects that are as much as 100 times more massive than our own sun. Among the reports is a July 29, 2017, signal that represents the most distant, most energetic, and most massive black hole collision detected so far. That collision happened about five billion years ago — even before the birth of our sun — and released an amount of energy equivalent to converting almost five solar masses to gravitational radiation.

What We Learn from Black Hole Observations

Black holes are among the few objects in the universe massive and dense enough to produce gravitational waves that can be measured, said Sudarshan Ghonge, a CRA graduate student and also a member of the collaboration. But those measurements can be quite worthwhile.

“These waves have signatures that depend on the properties of the black holes from which they originated,” he said. “By measuring these waves, we can infer the masses, spin, sky location, and distance from us. It’s similar to how you can listen to a sound and roughly figure out where it’s coming from, how far away it is, and what’s causing it.”

LIGO works by observing infinitesimally small changes caused by gravitational waves passing through the Earth. The changes affect laser beams traveling through twin four-kilometer arms of the L-shaped observatories. The Hanford and Livingston facilities, separated by 1,865 miles, confirm the observations, as both facilities should detect the waves. Additional information comes from the Virgo facility in Italy.

Observing Runs Produce New Records

From September 12, 2015, to January 19, 2016, during the first LIGO observing run since undergoing upgrades in a program called Advanced LIGO, gravitational waves from three binary black hole mergers were detected. The second observing run, which lasted from November 30, 2016, to August 25, 2017, yielded one binary neutron star merger and seven additional binary black hole mergers, including the four new gravitational wave events reported December 1. The new events are known as GW170729, GW170809, GW170818 and GW170823, in reference to the dates they were detected.

GW170814 was the first binary black hole merger measured by the three-detector network made possible by collaboration between LIGO and Virgo, and allowed for the first tests of gravitational wave polarization, which is analogous to light polarization.

One of the new events, GW170818, detected by the global network formed by the LIGO and Virgo observatories, was very precisely pinpointed in the sky. The position of the binary black holes, located 2.5 billion light-years from Earth, was identified in the sky with a precision of 39 square degrees. That makes it the next-best localized gravitational wave source after the GW170817 neutron star merger.

The event GW170817, detected three days after GW170814, represented the first time that gravitational waves were observed from the merger of a binary neutron star system. What’s more, this collision was seen in gravitational waves and light, marking an exciting new chapter in multi-messenger astronomy, in which cosmic objects are observed simultaneously in different forms of radiation.

Advancing Gravitational Wave Observation

“The release of four additional binary black hole mergers further informs us of the nature of the population of these binary systems in the universe and better constrains the event rate for these types of events,” said Caltech’s Albert Lazzarini, deputy director of the LIGO Laboratory.

“In just one year, LIGO and Virgo working together have dramatically advanced gravitational wave science, and the rate of discovery suggests the most spectacular findings are yet to come,” said Denise Caldwell, director of NSF’s Division of Physics. “The accomplishments of NSF’s LIGO and its international partners are a source of pride for the agency, and we expect even greater advances as LIGO’s sensitivity becomes better and better in the coming year.”

“The next observing run, starting in Spring 2019, should yield many more gravitational wave candidates, and the science the community can accomplish will grow accordingly,” said David Shoemaker, spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and senior research scientist in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “It’s an incredibly exciting time.”

“It is gratifying to see the new capabilities that become available through the addition of Advanced Virgo to the global network,” said Jo van den Brand of Nikhef (the Dutch National Institute for Subatomic Physics) and VU University Amsterdam, who is the spokesperson for the Virgo Collaboration. “Our greatly improved pointing precision will allow astronomers to rapidly find any other cosmic messengers emitted by the gravitational wave sources.” The enhanced pointing capability of the LIGO-Virgo network is made possible by exploiting the time delays of the signal arrival at the different sites and the so-called antenna patterns of the interferometers.

The scientific papers describing these new findings, which are being initially published on the arXiv repository of electronic preprints, present detailed information in the form of a catalog of all the gravitational wave detections and candidate events of the two observing runs as well as describing the characteristics of the merging black hole population. Most notably, we find that almost all black holes formed from stars are lighter than 45 times the mass of the sun. Thanks to more advanced data processing and better calibration of the instruments, the accuracy of the astrophysical parameters of the previously announced events increased considerably.

Added Georgia Tech professor Laura Cadonati, deputy spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, “These new discoveries were only made possible through the tireless and carefully coordinated work of the detector commissioners at all three observatories, and the scientists around the world responsible for data quality and cleaning, searching for buried signals, and parameter estimation for each candidate — each a scientific specialty requiring enormous expertise and experience.”