When Tomas Lowenstein of Agricola La Reina, a mushroom farm in Miranda, Venezuela, needs spawn, or “seed,” to grow his crops, his chosen point of contact isn’t around the corner or even in the country. It’s more than 2,200 miles away in a laboratory on Penn State’s University Park campus.

“For the past 12 years, we have been buying (spawn) cultures from Penn State,” said Lowenstein, who manages the 30-year-old mushroom company. “And since then, the quality of our mushrooms has improved 100 percent.”

Agricola La Reina is among many commercial mushroom farms, academic researchers and mushroom hobbyists from near and far that rely on the Penn State Mushroom Spawn Lab in the College of Agricultural Sciences to advance their operations.

This service is especially important for Pennsylvania’s mushroom industry, which leads the United States in mushroom production, with an output in 2017 valued at $764 million, according to the American Mushroom Institute. The industry also supports 8,600 jobs in the state.

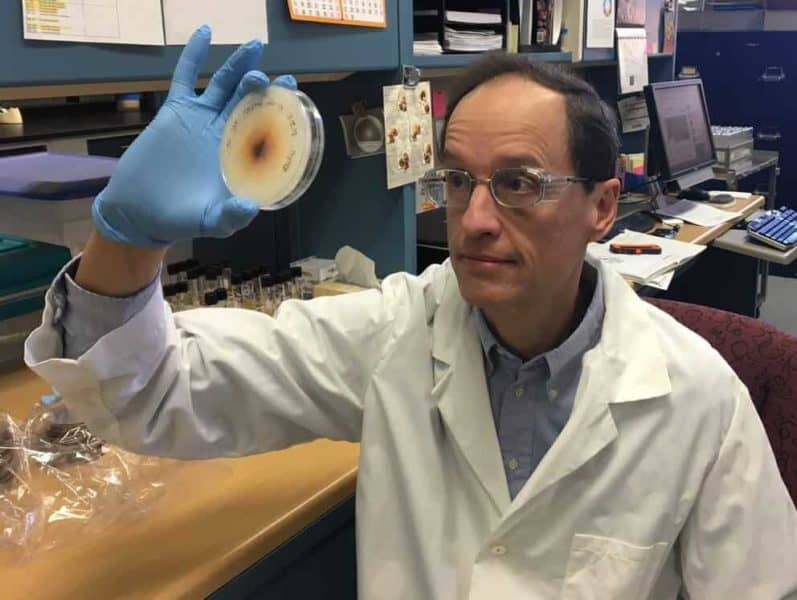

“Penn State has been at the forefront of research and educational programs to assist the mushroom industry since the mid-1920s,” said Ed Kaiser, research technologist, who, under the guidance of John Pecchia, lab director and assistant professor, leads the operation located in the Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology.

“Our state-of-the-art spawn lab is an outgrowth of that program, using our expertise to assist companies from Pennsylvania and around the world to grow high-quality, disease-free mushrooms so they can meet an ever-growing consumer demand.”

Mushrooms are fungi in a kingdom separate from plants and animals. Spawn is the material needed to grow mushrooms, much like seeds used to grow fruits and vegetables. As a mushroom matures, Kaiser explained, it produces millions of microscopic spores on mushroom gills lining the underside of a mushroom cap. However, growers do not use mushroom spores to “seed” mushroom compost because they develop unpredictably and, therefore, are not reliable.

Rather, they use spawn, which is created by inoculating a pure culture of vegetative mycelium — thread-like fungal cells — onto various grains. These cultures develop and grow and then are used to inoculate compost or substrate. From the compost or substrate, the mushroom fruiting bodies will emerge.

Kaiser admitted that the process can sound complicated but offered an analogy that might help: “Think of the mycelium as the tree and mushrooms as its apples.”

Only specialized facilities, such as the one at Penn State, have the expertise, technology and sterile environment to grow mushroom mycelia that are free of contaminants, said Kaiser, whose background is in chemistry and instrumental analysis.

The Penn State Mushroom Spawn Lab has an extensive collection of more than 280 strains, or varieties, of which Agaricus bisporus — commonly known as the white button — is the most popular and available for purchase. Pennsylvania produces approximately 64 percent of the white button mushrooms grown in the United States.

The lab also carries more than 700 strains of 202 species of commercial and wild mushrooms, including consumer favorites Lentinula edodes (shiitake), Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster) and Volvariella volvacea (paddy straw). Mushrooms produced from the cultures vary in size, shape, degree of smoothness and shrinkage during processing, factors that are important in mushroom cultivation.

“Penn State has amassed one of the most extensive collections of commercial and wild mushroom strains, representing varieties from all over the world,” Kaiser said. “Our collection continues to grow, as more isolates are submitted to us from partners nationally and internationally.”

Complementing the spawn culture collection is a separate collection of more than 250 strains of diseases relevant to mushroom production. These samples, submitted by scientists at Penn State and other institutions, are used for research projects focusing on the prevention and treatment of bacterial and fungal diseases on cultivated mushrooms.

In addition to research, Penn State offers educational programs, including the industry-focused Mushroom Short Course, which recently celebrated its 60th anniversary; a mushroom science and technology minor, which is designed to prepare students for a career in the mushroom industry; and ongoing Penn State Extension seminars.

“The Penn State Spawn Lab has served as a unique public microbial resource for mushroom spawn for nearly a century,” said Carolee Bull, head of the Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology. “Under the leadership of Dr. John Pecchia and Ed Kaiser, we are confident the program will be even more valuable in its second 100 years.”

More information about the Mushroom Spawn Lab can be found online at https://plantpath.psu.edu/facilities/mushroom.