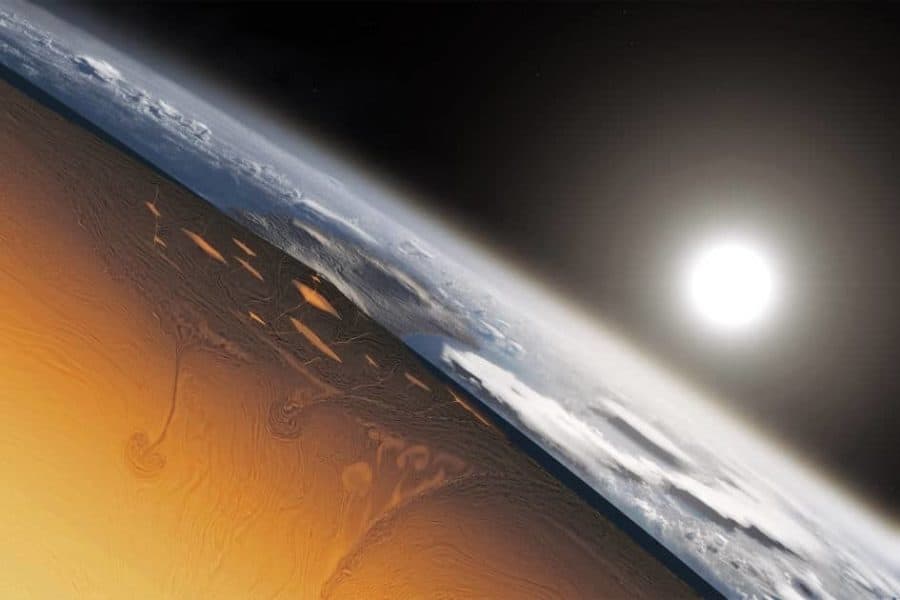

Plate tectonics is key to the evolution of life and the development of the planet. Today, the Earth’s outer shell consists of about 15 shifting blocks of crust. On them sit the planet’s continents and oceans. As Earth formed, the plates drifted into each other and apart, exposing new rocks to the atmosphere, which led to chemical reactions that stabilized Earth’s surface temperature over billions of years. A stable climate is crucial to the evolution of life, and the study suggests that early forms of life came about in a more moderate environment.

“We’re trying to understand the geophysical principles that drive the Earth,” said Roger Fu, one of the paper’s lead authors and an assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “Plate tectonics cycles elements that are necessary for life into the Earth and out of it.”

Plate tectonics helps planetary scientists understand worlds beyond this one, too.

“Currently, Earth is the only known planetary body that has robustly established plate tectonics of any kind,” said Brenner, a third-year graduate student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “It really behooves us as we search for planets in other solar systems to understand the whole set of processes that led to plate tectonics on Earth and what driving forces transpired to initiate it. That hopefully would give us a sense of how easy it is for plate tectonics to happen on other worlds, especially given all the linkages between plate tectonics, the evolution of life, and the stabilization of climate.”

For the study, members of the project traveled to the Pilbara Craton. A craton is a primordial, thick, and very stable piece of crust. They are usually found in the middle of tectonic plates and are the ancient hearts of the Earth’s continents, which makes them the natural place to go to study the early Earth. The Pilbara Craton stretches about 300 miles across, covering approximately the same area as the state of Pennsylvania.

Fu and Brenner drilled into rocks from a portion called the Honeyeater Basalt and collected core samples about an inch wide in 2017. They brought them back to Fu’s lab in Cambridge and placed them into magnetometers and demagnetizing equipment. Certain minerals in rocks lock in the direction and intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field at the time they are formed. That field shifts over time, so by examining layers, scientists glean evidence for a kind of timeline of when rocks were formed and when they shifted in the plates. These instruments told them the rock’s magnetic history — the most stable bit being when the rock formed, which was 3.2 billion years ago.