When the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act was authorized in 1976 (also known as the 4R Act) it had been 10 years since the High Speed Ground Transportation Act of 1965, introduced by Congress, passed. Interest seemed strong through the 1980s and ’90s but funding for and forward momentum in this direction failed to materialize.

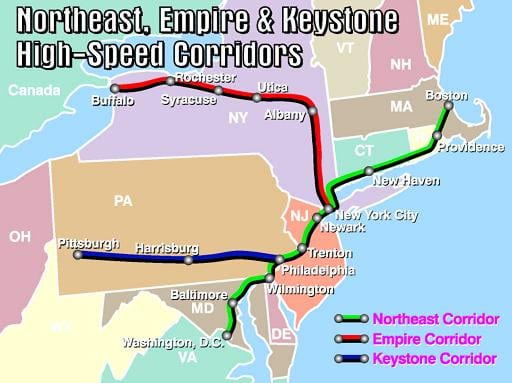

Now, almost 45 years later, the Transportation Technology Center located some 25 miles from Pueblo, Colorado is the facility where one of Amtrak’s new 160 mph-capable Acela high-speed trainsets is currently undergoing extensive testing. This is being done in preparation for actual service on the National Railroad Passenger Corporation’s 457-mile-long Northeast Corridor (NEC) set to begin in 2021.

Making tracks for faster trains

The newest Acela’s, a product of Alstom, will replace the now 20-year-old versions from Canadian builder Bombardier, in use in the NEC Boston-to-Washington, D.C. service lane since year 2000. These trains, due to railway track limitations, are restricted to 150 mph; only two relatively short stretches on the corridor permit this high a speed.

And, this is only the beginning. Another electrified high-speed train service, this time planned for the western U.S., is XpressWest’s initial 180-mile-long Las Vegas, Nevada to Victorville, California pike, the start of operations estimated to be in 2023 with eventual extension to Los Angeles, this along with a proposed tie-in in Palmdale, in the Golden State’s high-desert region, one that would enable a direct connection to California’s own high-speed rail project there when it arrives: More on the California system in a bit. Max speed is expected to be 150 mph and indications are that project groundbreaking will commence late this year.

With the Texas Central Railroad and Infrastructure, Incorporated’s program now declared an actual railroad by a Texas appellate court recently, unless an appeal is filed and advanced by interests opposed, presumably at the State Supreme Court level, could be up and running as soon as 2025 or 2026, according to information on the company website. Construction cost of the 240-mile-long Dallas-to-Houston line is estimated to be $14 billion, approximately $20 billion being the project’s total investment. Maximum speed for trains making the presumed 90-minute trip is an even faster 205 mph.

And, the fastest of all is, of course, California’s planned Phase 1, 520-mile-long network linking Los Angeles and Anaheim in the coastal south with San Francisco in the coastal north, trains to operate at a top speed of 220 mph. Non-stop L.A.-S.F. and S.F.-L.A. are held, according to language spelled out in the Safe, Reliable High-Speed Passenger Train Bond Act for the 21st Century (California Proposition 1A passed by 52.6 percent of state voters in 2008) in 2 hours, 40 minutes total, meaning an average speed of 195 mph must be maintained. The complete Phase 1 infrastructure package, estimated to be in place by 2033, will be built to 250 mph standards. Total projected cost: some $80 billion.

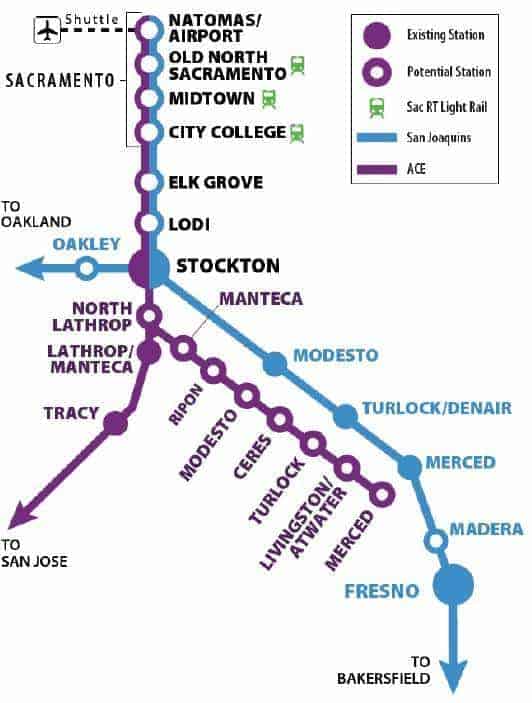

In the meantime, as it currently stands, California’s is the only project with actual construction work begun. Train testing is slated to commence by 2026 with full service being available on 171 miles of track between Bakersfield and Merced. This stretch’s investment plus that of electrification work on 47 miles of currently active Caltrain line between San Francisco and San Jose, $20.4 billion.

Planned for the interim until California high-speed rail reaches from the San Joaquin Valley to the San Francisco peninsula is what is referred to as Valley Rail, a collaboration between the San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority (operator of the Amtrak San Joaquin passenger trains) and the San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission (which manages the Altamont Corridor Express – ACE – service).

As road-based travel becomes more constrained what with the growth in population coupled with driving on the rise and roadway capacity upgrades being modest at best, the need for alternative solutions becomes self-evident and ever more relevant. As to those alternative solutions rail, more often than not, has proven to be the best bet. Not only where speed is a factor, but with regard to a host of other benefits and features.

“ … dollar for dollar, railways go so much farther in terms of handling capacity than do highways, all things being equal,” the railways thus have the far better value. This was explained in detail in “Rails vs roads for value, utilization, emissions-savings: difference like night and day” here.

The Association of American Railroads furthermore notes that truckloads in the hundreds can be removed from highways via a single freight train move, that action not only providing a sort of relief valve so to speak for limited-capacity highway infrastructure, but in providing relief to the air as well. (See: “Trains: No better mode than rail for providing air (pollution) relief” here).

American high-speed rail: Coming soon!

Images: Federal Railroad Administration (upper); San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority (lower)

This post was last revised on May 25, 2020 @ 6:58 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time.