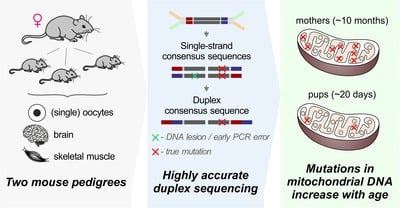

Older mice have more new mutations — changes in DNA sequence that occur in the individual rather than being inherited from a parent — than younger mice in the genomes of their mitochondria, according to researchers at Penn State. The findings could have implications in humans because mutations in the mitochondrial genome are associated with multiple human genetic diseases and these new mutations can be passed to the next generation by mothers who often have children at older ages in modern societies.

The researchers used an extremely accurate DNA sequencing method to sequence the entire genome of mitochondria — organelles that are the powerhouse of the cell — in both reproductive cells and other cells in the body and showed that, depending on the cell type, ten-month-old mother mice had approximately two-to-three times more new mutations than their nearly one-month-old pups.

The study is the first to directly measure new mutations across the whole mitochondrial genome in reproductive cells.

“Previous studies identified new mutations by comparing DNA sequence between parents and offspring, rather than looking directly at the reproductive cells,” said Kateryna Makova, Pentz Professor of Biology at Penn State and the leader of the research team. “This could provide a biased picture of the rate and pattern of new mutations, because selection could prevent some mutations, for example those that are incompatible with life, from ever being seen.”

A paper describing the study, led by researchers at Penn State, appears July 15 in the journal PLOS Biology.

“It’s been extremely difficult to study new mutations occurring in individuals and cells directly because the error rates of DNA sequencing technologies are so much higher than the mutation rate,” said Makova. “Thus, we frequently did not know if changes in DNA sequence that we see were new mutations or just errors in the sequencing. In our new study, we used an advanced and extremely accurate sequencing method so that we can be confident that we are observing actual new mutations.”

The team used a technique called “duplex sequencing” to determine the order of DNA letters in the complete mitochondrial genomes from brain cells, muscle cells, and oocytes — female reproductive cells that form eggs — from 10-month-old mice and their one-month-old pups. If you think of a DNA molecule as a twisted ladder, you can split it down through the middle of the rungs and each side is called a strand. Most DNA sequencing methods only look at one strand of the DNA molecule at a time. Duplex sequencing reads both DNA strands and compares the two to reduce its error rate.

“To reduce errors, modern ‘next-generation’ sequencing technologies can read many, many copies of a sequence,” said Barbara Arbeithuber, a postdoctoral researcher at Penn State and first author of the paper. “The different reads of the same sequence will have errors in different spots, so we can compare all these reads and build what is called a ‘consensus’ sequence. Duplex sequencing does this for both strands independently, then further reduces errors by comparing the consensuses for the two strands. This usually requires a fairly large amount of DNA starting material, so we had to optimize the protocol to deal with tiny amounts of DNA from single oocytes.”

When the team compared the mitochondrial genome sequences of the mother mice and their pups, they found an increase in the number of mutations in the older mice for all of the tissues that they tested. This suggests that as the mice age, their mitochondrial genomes accumulate mutations, so the team wanted to know if they could identify the source of these mutations.

Mutations can occur because of errors in DNA replication when a cell divides and makes copies of its genetic material for each of the resulting daughter cells. They can also be caused by environmental factors like UV light or radiation, for example, or if there are errors during DNA repair.

“When we looked at the pattern of mutations in the mitochondrial genomes it fit with what we would expect for most of them occurring through replication errors,” said Arbeithuber. “But we also observed some differences in the mutation patterns between oocytes and body cells. This suggested that the contribution of different molecular mechanisms to mitochondrial mutations varies among these cells.”

Body, or somatic, cells — like brain and muscle cells — undergo many cycles of cell division and continue to do so throughout life. Oocytes, in contrast, only divide a limited number of times, which mainly occur early in development and then enter a sort of stasis until they are needed later in life.

“Given that they undergo different numbers of cell divisions, it makes sense that the contribution of various mechanisms to the mutation process might be different between the tissues,” said Makova. “However, because we see some evidence of replication error mutations in the mitochondrial genomes of oocytes as well, it’s possible that there is turnover of mitochondrial genomes in oocytes even though the cells are not dividing themselves.”

The researchers suggest that the accumulation of mutations that they see in the mitochondrial genomes of the mother mice could have implications for understanding of human reproductive health.

“We see a two-to-three-fold increase of mutations in mother mice after only nine months,” said Makova. “It will be important to see how this rate of increase compares to humans, because we have a much longer amount of time before we begin reproducing and, in many societies, that time is increasing and reproduction is being delayed to later and later ages.

In addition to Makova and Arbeithuber, the research team at Penn State includes James Hester, Marzia A. Cremona (now a professor at Laval University in Canada), Nicholas Stoler, Arslan Zaidi (now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania), Bonnie Higgins, Kate Anthony, Francesca Chiaromonte and Francisco J. Diaz.

The research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Austrian Science Fund, the Penn State Eberly College of Science Office of Science Engagement, the Huck Institute of Life Sciences and the Institute for Computational and Data Sciences at Penn State, as well as, in part, under grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement and CURE Funds.