One way to cut back on deforestation in the Amazon rainforest – and help in the global fight against climate change – is to grant more of Brazil’s indigenous communities full property rights to tribal lands. This policy focus is suggested by a new University California of San Diego study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Led by UC San Diego political science researcher Kathryn Baragwanath, the study uses an innovative method to combine satellite data of vegetation coverage in the Amazon rainforest, between 1982 and 2016, with Brazilian government records of indigenous property rights. The study found significantly reduced deforestation rates in territories that are owned fully and collectively by local tribes – when compared to territories that are owned only partially by the tribes or not at all. The average effect was a 66% reduction in deforestation.

The Amazon accounts for half of the Earth’s remaining tropical forest, is an important source of the biodiversity on our planet and plays a major role in climate and water cycles around the world. Yet the Amazon basin is losing trees at an alarming rate, with particularly high levels in recent years, due to a combination of massive forest fires and illegal activities.

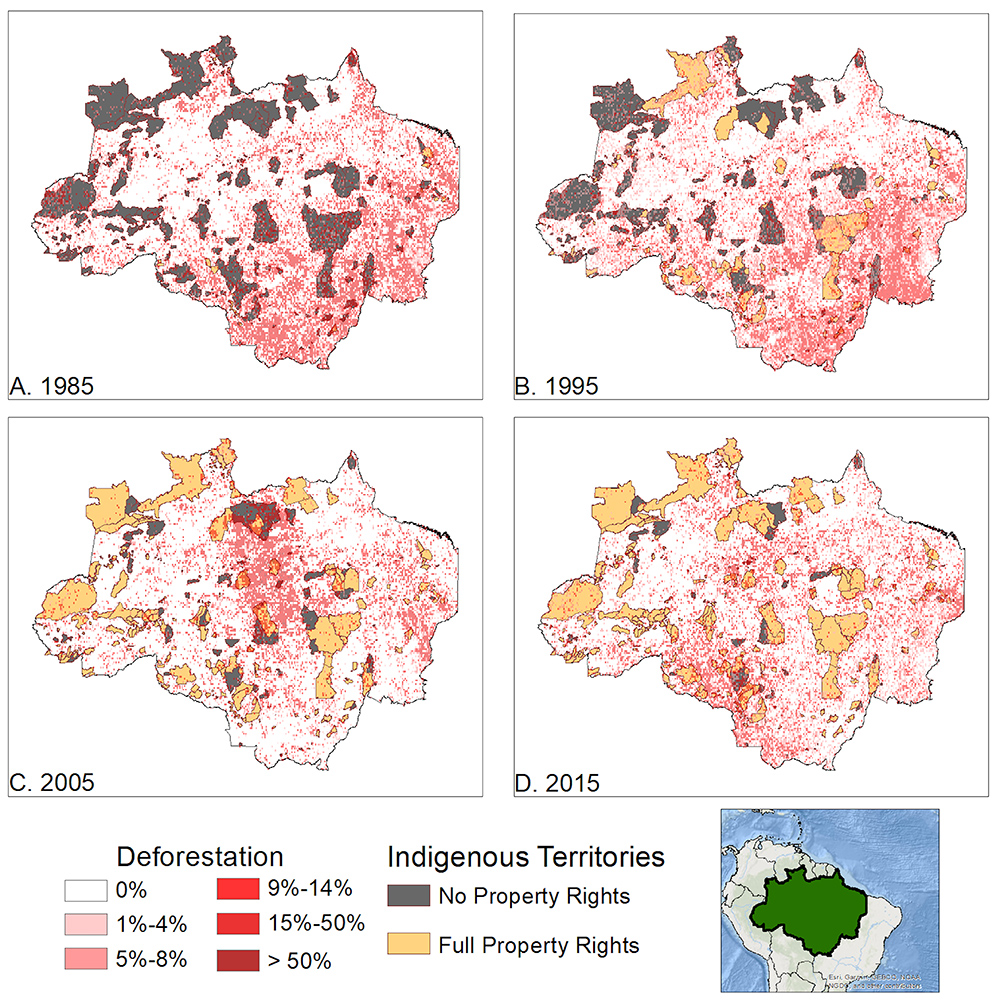

Indigenous territories and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon for 1985, 1995, 2005 and 2015. Deforestation is significantly reduced in territories with full property rights. Graphic courtesy Kathryn Baragwanath, UC San Diego.

Indigenous territories and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon for 1985, 1995, 2005 and 2015. Deforestation is significantly reduced in territories with full property rights. Graphic courtesy Kathryn Baragwanath, UC San Diego.Who owns the Amazon, meanwhile, is hotly contested, with numerous actors vying for the privilege. Some private entities go ahead with illegal mining or logging, for example, to demonstrate “productive use of land” and thereby gain title to that land. At present, about 2 million hectares of indigenous land are still awaiting official designation as tribal territories.

Also debated is whether collective property rights are effective in curbing deforestation. These rights are granted to indigenous peoples in Brazil through a complex and lengthy constitutional process, and are distinct from the private property rights most of us are more familiar with.

UC San Diego’s Baragwanath and co-author Ella Bayi, now at Columbia University, say “yes, collective property rights are effective” – if you focus your analysis on the final stage of the titling process in Brazil (which can take up to 25 years to complete), or the point at which tribes gain full property rights.

Full property rights give indigenous groups official territorial recognition, enabling them not only to demarcate their territories but also to access the support of monitoring and enforcement agencies, the researcher say.

“Our research shows that full property rights have significant implications for indigenous people’s capacity to curb deforestation within their territories,” said Baragwanath. “Not only do indigenous territories serve a human rights role, but they are a cost-effective way for governments to preserve their forested areas and attain climate goals. This is important since many indigenous territories have yet to receive their full property rights and it points to where policymakers and NGOs concerned about the situation in Brazil should now focus their efforts.”

Baragwanath is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science in UC San Diego’s Division of Social Sciences. Bayi is now a political science graduate student at Columbia University. The PNAS study began as Bayi’s senior honor’s thesis when she was an undergraduate student at UC San Diego and Baragwanath was her T.A.

MEDIA CONTACT

Inga Kiderra, 858-822-0661, [email protected]