The paradox: In animal models there is a consistent relationship between eating less and living longer. But studies in humans find that people who are a little overweight live longest.

Last week, I introduced this paradox and offered evidence, both that lab animals live longer when they are underfed, and that humans live longer when they are overfed. In the article below, I introduce nuances and confounding factors, but in my opinion, the paradox remains unresolved.

BMI

BMI is an imperfect measure of how fat or thin someone is for his height. That’s because it is calculated with the square of height, but body volume (for a given shape) is proportional to the cube of height. The result is that tall people will have a higher BMI than shorter people with equivalent proportions of body fat. For example, BMI=20 for a person 5 feet tall means a weight of 102 pounds, an average weight for that height; whereas BMI=20 for a person 6 feet tall means a weight of 147, which is borderline emaciated.

Short people tend to live significantly longer than tall people, and the effect is substantial. Males under 5’7” live 7½ years longer than males over 6’ [ref]. This fits with the fact that short people tend to have less growth hormone in their youth. There is a genetic variant in parts of Ecuador that prevents growth hormone from transforming to IGF1 (Laron dwarfism); these people are generally about 4 feet tall and tend to live longer. From domesticated animals, we also know that small dogs live longer than large dogs, small horses longer than large horses. Between species, larger animals live longer, but within a single species, smaller animals live longer.

The height association deepens the weight paradox, because short people will tend to have a lower BMI, which we would expect to skew the association of BMI with longevity downward.

Growth Hormone and IGF1

Growth hormone (which is translated into IGF1 in the body) is genetically associated with shorter lifespan, but we have more of it when we’re young and it promotes a body type with more muscle, less fat. According to this Japanese study, IGF1 increases with weight for people who are thin, but decreases with weight for people who are fat. So maximum longevity is close to maximum IGF1.

Here are some partial explanations for the paradox.

Most variation in weight is explained by genetics, not food intake. The explanation I have proposed in the past is that the CR effect is about food intake, not genetics. And people who are congenitally stout are more likely to be restricting their calories. CR humans are not necessarily especially thin.

The CR effect is proportionately smaller in long-lived humans than in short-lived rodents or shorter-lived worms and flies. [ref] If life extension via CR evolved to help an animal survive a famine, then it seems reasonable that the benefit should be limited to a few years, because that is as long as most famines in nature are likely to last.

The CR effect may be due to intermittent fasting rather than total calorie intake. Traditional CR experiments conflate intermittent fasting with overall calorie reduction, because food is provided in a single daily feeding, and hungry rodents gobble it up, then go hungry for almost 24 hours. More recent experiments attempt to separate the effect of limited-time eating from the effect of calorie reduction, and the general conclusion is that both benefit longevity. It may be that humans who are skinny tend to graze all day, while people with a comfortable amount of fat more easily go for hours at a time without eating.

Mice carry less fat, have less food craving, and have better gut microbiota if they are fed at night rather than during the day [ref]. Mice are active nocturnally; so translating to humans, it probably means that we should eat in the morning. Conventional wisdom is that eating earlier in the day is better for weight loss and health [ref], but I know of no human data on mortality or life span. This classic study in mice [1986] found caloric restriction itself was the only thing affecting lifespan, and there was no difference whether the mice were fed night or day, in three feedings or one.

Smokers tend to be thinner than non-smokers, but they don’t live longer for reasons that have to do with smoking, not weight. So this is a partial explanation why heavier BMI might be associated with longer lifespan. But note that the recent Zheng’s Ohio State study claimed there was no change in the best weight for longevity when correction was introduced for smoking.

Cachexia is a “wasting” disorder that causes extreme weight loss and muscle atrophy, and can include loss of body fat. This syndrome affects people who are in the late stages of serious diseases like cancer, HIV or AIDS, COPD, kidney disease, and congestive heart failure (CHF). [healthline.com] If cachexia subjects are not removed from a sample, it can strongly bias against weight loss, because once cachexia sets in, life expectancy is very short. But the Zheng study was based on Framingham data, collected annually over the latter half of a lifetime; Cachexia is not expected to be a significant factor.

Timing artifact – The Framingham study covers a 74-year period in which BMI is increasing and also lifespan is increasing, probably for different reasons. The younger Framingham cohort is living ~4 years longer than the older cohort and is ½ BMI point heavier. This could create an illusion that higher BMI is causing greater longevity. However, the Ohio State study made some effort to pull this factor out. Greater lifespan is associated with gradually increasing BMI, and this is true separately in both cohorts.

Differential effects on CVD and Cancer This chart (from Zheng) shows how the mortality burden of cardiovascular disease has decreased over the last century, but not so cancer.

But CV disease risk increases consistently with BMI, while cancer risk, not so much (also from Zheng):

| These numbers in parentheses are odds ratios from a Cox proportional hazard model. What they means is that a person in the Lower-Normal weight group had 20% less chance of getting heart disease compared to someone of the same age in the Normal-Upward group, but a 60% increased chance of getting cancer. These appear to be large, concerning numbers. But remember that the underlying probabilities are all increasing exponentially with age. Translated into years of lost life, 60% greater probability of cancer is only 1 year of life expectancy at age 50. (60% greater overall mortality would subtract 4½ years from life expectancy.) In my experience, hazard ratios in the range 0.7 to 1.5 don’t necessarily mean anything, because of the difficulties in interpreting data. The numbers in parenthesis after 1.60 in the above table (1.12 — 2.30) mean that statistical uncertainty alone is a range from 1.12 to 2.30.There are plenty of large effects with hazard ratios of 3 or more. For comparison, the hazard ratio for pack-a-day smokers getting lung cancer is 27. |

Zheng’s study found a longevity disadvantage to being underweight, and it was exclusively due to a higher cancer risk. In fact, incidence of cardiovascular disease among the lowest BMI class was lowest (0.8); but their cancer risk more than made up for it (1.6).

This means that as time goes on and most Americans are getting heavier, their risk of dying from CVD is blunted by improved technology. The mortality risk from CVD is down by 40% in this century [NEJM], while the cancer risk is unchanged [CDC]. So people are dying of cancer who would have died of CVD in previous generations.

This means that low BMI has less benefit for longevity than it used to have, and the trend over time tends to exaggerate the appearance that higher weight is protective against all-cause mortality.

Is it true that cancer risk does not go up with BMI?

The Framingham result is puzzling and difficult to reconcile with a well-established relationship between higher BMI and higher cancer risk. This review by Wolin [2010] finds a modest increase in risks of all common types of cancer associated with each 5-point gain in BMI. (The RR numbers are comparable to hazard ratios above.)

Lung cancer is the big exception, and Wolin explains the inverse relationship with BMI by the fact that people smoke to avoid gaining weight. This would suggest a resolution to the conflict with Zheng’s study, but for the fact that Zheng explicitly corrects for smoking status and finds it makes no difference at all — a result which is puzzling in itself.

Alzheimer’s Disease is the third leading cause of death, and the corresponding story is more complicated. Lower weight in middle age seems to be mildly protective, while it is certainly not protective in the older years when AD is most prevalent.

“Hazard ratios per 5-kg/m2 increase in BMI for dementia were 0.71 (95% confidence interval = 0.66–0.77), 0.94 (0.89–0.99), and 1.16 (1.05–1.27) when BMI was assessed 10 years, 10-20 years, and >20 years before dementia diagnosis.” [ref]

This, too, is unexpected in light of previous consensus. Alzheimer’s Dementia has been recast as Type 3 Diabetes, because of its strong association with insulin metabolism. Overweight is supposed to be the greatest life-style risk factor for diabetes. When this study [2009] out of U of Washington found that high BMI is protective against dementia, the authors were unwilling to draw the standard causal inference, so they conjectured instead that weight loss is a consequence of AD’s early stage.

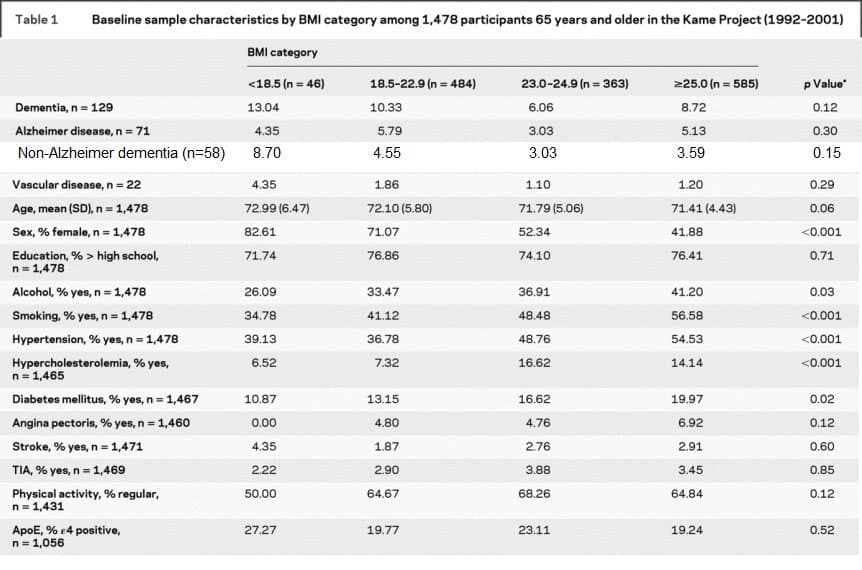

There may be a better explanation hidden in their data. AD is the most common cause of dementia, but vascular dementia, a separate etiology, accounts for roughly ⅓ of cases in the Kame data set:

There is a suggestion here that higher BMI protects against vascular dementia, but not against AD.

From you, my readers

Here are some of the suggestions offered in the comment section of last week’s blog:

- Fat people are happier. I don’t doubt that happiness has a lot to do with longevity but a lot of overweight is due to compulsive eating by people who are not happy with their lives. Obesity is associated with lower socio-economic status, and lower SES is independently associated with shorter lifespan and lower life satisfaction.

- Higher BMI can mean more muscle mass, not necessarily more fat mass. Good point. I don’t know how big a factor this is.

- This study [BMJ 2016] found greatest longevity for BMI in the range 20-22. I take your point that the larger studies with longer follow-up tend to report lower optimal BMI. The BMJ study is a meta-analysis of a huge database covering 9 million subjects.

- Dean Pomerleau writes at the CR Society web page about brown fat, cold resistance, and greater longevity.

- Thin people have greater insulin sensitivity, which can lead to glucose going into cells instead of being stored as fat. This is interesting, and deserves more follow-up. But good insulin sensitivity also means lower blood sugar, so it’s not obvious to me which direction the effect ought to go.

- I was grateful for a pointer to Valter Longo’s recent work, recommending that time-restricted eating becomes counterproductive after about 13 hours a day of fasting. Longer fasts several times a year are still highly recommended.

- Paul Rivas is my go-to authority on weight, and he recommended this 2015 study, which emphasizes the paradox as I describe it.

- This study out of Emory U [2019] recommends different diets for different BMI groups for minimizing inflammation.

What story does methylation tell?

Aside from mortality statistics, I regard methylation age as the most reliable leading indicator we have. I’ll end by reviewing data on BMI and methylation age.

The Regicor Study [2017] looked for methylation sites associated with obesity. They reported 97 associated with high BMI and an additional 49 associated with large waistline. I compared their lists with my list of methylation sites that change most consistently with age. There was no overlap. What I learn from this is that there is no association with genetically-determined weight and longevity. If you were born with genes that make you gain weight, there is a social cost to be paid in our culture, but there is no longevity penalty.

Horvath [2014] did not discern a signal for obesity with the original 2013 DNAmAge clock, except in the liver where the signal was weak, amounting to just 3 years for the difference between morbidly obese and normal weight. But a few years later with 3 different test groups [2017], a moderate signal was found, as expected, linking higher BMI to greater DNAmAge acceleration. (Age acceleration is just the difference between biological age as measured by the methylation clock and chronological age by the calendar.)

This study [2019] from the European Lifespan Consortium found a modest increased mortality from obesity, corresponding to less than a year of lost life by most measures, based on two Horvath clocks and the Hannum clock. This Finnish study [2017] found a small association between higher BMI and faster aging in middle-aged adults, but not in old or young adults.

This study from Linda Partridge’s group [2017] found a strong benefit of caloric restriction on epigenetic aging—in mice, not in humans.

I’ve had a good time with this project, seeking explanations for the paradox, and I’ve passed along some interesting associations, but in the end, the essential paradox remains. I don’t know why the robust association of caloric restriction with longevity doesn’t lead to a clear longevity advantage in humans for a lower BMI. My strongest insight is that the largest determinants of BMI are genetic, not behavioral, and the genetic contribution to weight has no effect on longevity. But what do I make of the fact that life expectancy in the US has risen by a decade over my lifetime [ref] even as BMI has increased 5 points.