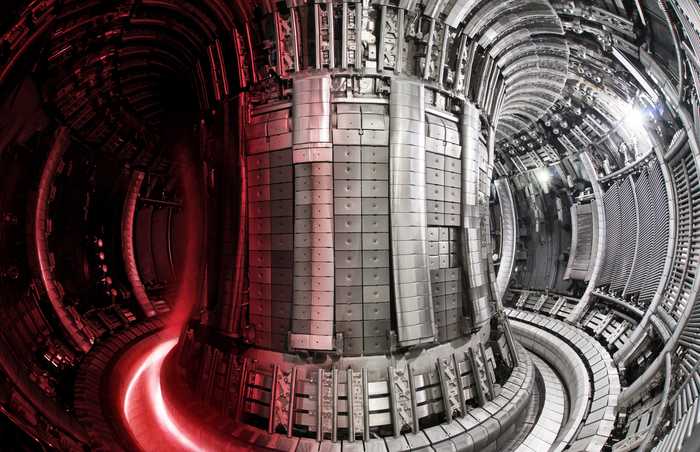

Following the example of the sun, fusion power plants aim to fuse the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium and release large amounts of energy in the process. The only plant in the world currently capable of operating with such fuel is the European joint project JET, the Joint European Torus in Culham near Oxford, UK. However, the last experiments with the fuel for future fusion power plants were conducted there in 1997. Because tritium is a very rare raw material that also poses special handling challenges, research teams usually use hydrogen or deuterium for plasma experiments. In future power plants, tritium will be formed from lithium during energy production.

Experiments with deuterium-tritium mixtures in preparation for ITER

“We can explore the physics in fusion plasmas very well by working with hydrogen or deuterium, so this is the standard worldwide,” explains IPP’s Dr. Athina Kappatou, who with her IPP colleagues Dr. Philip Schneider and Dr. Jörg Hobirk led significant parts of the European collaborative experiments at JET.” However, for the transition to the international, large-scale, fusion experiment ITER, it is important that we prepare for the conditions prevailing there.” ITER is currently under construction in Cadarache, in southern France, and is expected to be able to release ten times as much energy as is fed into the plasma in terms of heating energy, using deuterium-tritium fuel.

To bring the JET experiment as close as possible to future ITER conditions, the previous carbon lining of the plasma vessel was replaced by a mixture of beryllium and tungsten, as is also planned for ITER, between 2009 and 2011. The metal tungsten is more resistant than carbon, which, moreover, stores too much hydrogen. However, the now metallic wall places new demands on the quality of the plasma control. The current experiments demonstrate the successes of the researchers: At temperatures ten times higher than those at the center of the sun, record levels of generated fusion energy have been achieved.

World record under ITER-like conditions

Prior to the change of the wall material, JET had set the world energy record in 1997 with a plasma that produced 22 megajoules of energy. This record stood until now. “In the latest experiments, we wanted to prove that we could create significantly more energy even under ITER-like conditions,” explains IPP physicist Dr. Kappatou. Several hundred scientists and researchers were involved in years of preparation for the experiments. They used theoretical methods to calculate in advance the parameters they needed to obtain to generate the plasma in order to achieve their goals. The experiments confirmed the predictions in late 2021 and delivered a new world record: JET produced stable plasmas with deuterium-tritium fuel that released 59 megajoules of energy.

To produce net energy – that is, to release more energy than the heatering systems provide – the experimental facility is too small. This will not be possible until the larger-scale ITER experiment in southern France comes online. “The latest experiments at JET are an important step toward ITER,” concludes Prof. Sibylle Günter, Scientific Director of the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics. “What we have learned in the past months will make it easier for us to plan experiments with fusion plasmas that generate much more energy than is needed to heat them.”

Background information: Megawatts vs. Megajoules

In the recent record-breaking experiment, the fusion reactions in JET released a total of 59 megajoules of energy in the form of neutrons during a five-second phase of a plasma discharge. Expressed in units of power (energy per time), JET achieved a power output of just over 11 megawatts averaged over five seconds. The previous energy record, set in 1997, was just under 22 megajoules of total energy and 4.4 megawatts of power averaged over five seconds.

About JET

JET was jointly designed and built by the members of the European fusion program EUROfusion and has been jointly operated since 1983. The English fusion center “Culham Centre for Fusion Energy” in Culham near Oxford is responsible for the technical operations, while temporarily seconded researchers and technicians from the EUROfusion laboratories work on the facility on a campaign basis. With numerous secondments, IPP is an important participant in the JET program.

About Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics

The research conducted at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics (IPP) in Germany (locations: Garching near Munich and Greifswald) is concerned with investigating the physical basis of a fusion power plant. Like the sun, such a plant aims to generate energy from fusion of atomic nuclei. IPP’s research is part of the European fusion program. With its workforce of approximately 1,100 IPP is one of the largest fusion research centers in Europe.