You’re out jogging and suddenly notice a low-hanging tree branch in your path. You quickly lower your head, narrowly avoiding the branch, and continue on the run without giving it another thought. But how did your brain help you so rapidly and precisely duck out of the way of the branch while running?

Researchers at the University of Michigan have now discovered a very fast brain rhythm that helps your left brain and right brain communicate better as you run faster—and even when you dream.

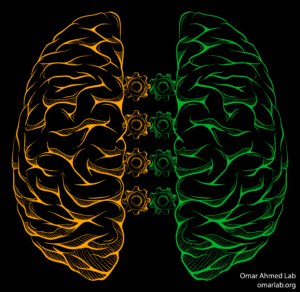

The fast rhythm linking the left and right halves of the brain has a new name: “splines,” so-called because they visually resemble mechanical splines, the interlocking teeth on mechanical gears.

Omar Ahmed, assistant professor of psychology and lead author of a new study appearing in Cell Reports, says that splines represent a pattern of rhythmic communication across the left and right brain that is different from other known brain rhythms.

“Previously identified brain rhythms are akin to the left brain and right brain participating in synchronized swimming: The two halves of the brain try to do the same thing at the exact same time,” he said. “Spline rhythms, on the other hand, are like the left and right brains playing a game of very fast—and very precise—pingpong. This back-and-forth game of neural pingpong represents a fundamentally different way for the left brain and right brain to talk to each other.”

Study first author Megha Ghosh, doctoral student in psychology, says splines serve a key function in allowing the left and right brain to coordinate information.

“These spline brain rhythms are faster than all other healthy, awake brain rhythms,” she said. “Splines also get stronger and even more precise when running faster. This is likely to help the left brain and right brain compute more cohesively and rapidly when an animal is moving faster and needs to make faster decisions.”

Splines are also seen during rapid eye movement, or REM, sleep—when most dreams happen, Ahmed says.

“Surprisingly, this back-and-forth communication is even stronger during dream-like sleep than it is when animals are awake and running,” he said. “This means that splines play a critical role in coordinating information during sleep, perhaps helping to solidify awake experiences into enhanced long-term memories during this dream-like state.”

The new findings focus on a part of the brain called the retrosplenial cortex. This region helps us figure out when to turn left vs. right, and is also important for memory and imagining the future. Importantly, it is also one of the first brain regions to become impaired in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

“We studied many different brain regions, and splines were consistently strongest in the retrosplenial cortex.” Ahmed said. “Given that the retrosplenial cortex is altered very early in Alzheimer’s disease, this means that we may be able to use spline rhythms in people as an early biomarker for Alzheimer’s. We are currently investigating this possibility in preclinical models of neurodegenerative diseases.”

The study’s other authors—all members of Ahmed’s lab at the U-M Department of Psychology—are Fang-Chi Yang, Sharena Rice, Vaughn Hetrick, Alcides Lorenzo Gonzalez, Danny Siu, Ellen Brennan, Tibin John and Allison Ahrens.