Key Points

- Four of Uranus’ largest moons likely contain ocean layers between their cores and icy crusts.

- New computer modelling and re-analysis of data from NASA’s Voyager spacecraft led to this discovery.

- This finding could inform future missions to explore Uranus and its mysterious moon system.

A fresh look at data from NASA’s Voyager spacecraft and new computer modelling have led NASA scientists to believe that four of Uranus’ largest moons likely have ocean layers between their cores and icy crusts. The study is the first to explore the evolution of the interior structure and composition of all five large moons: Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, Oberon, and Miranda. The research suggests that four of these moons could hold oceans as deep as dozens of miles.

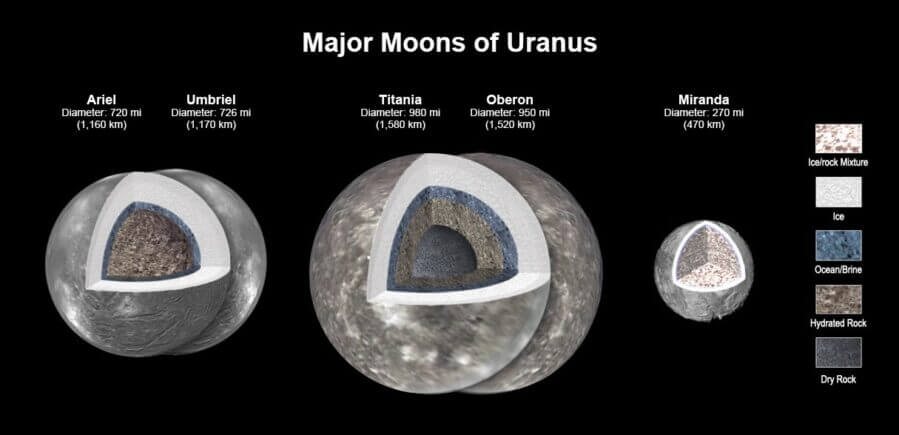

Uranus has at least 27 moons, with the four largest ranging from Ariel, at 720 miles (1,160 kilometres) across, to Titania, which is 980 miles (1,580 kilometres) across. Scientists have long believed that Titania, due to its size, would be most likely to keep internal heat caused by radioactive decay. The other moons were previously considered too small to retain the heat needed to stop an internal ocean from freezing, especially since heating created by Uranus’ gravitational pull is only a minor heat source.

The National Academies’ 2023 Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey prioritised exploring Uranus. To prepare for such a mission, planetary scientists are focusing on the ice giant to expand their knowledge of the mysterious Uranus system. The new work, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, could help plan how a future mission might investigate the moons. Lead author Julie Castillo-Rogez from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California said the paper also has implications beyond Uranus.

“When it comes to small bodies – dwarf planets and moons – planetary scientists previously have found evidence of oceans in several unlikely places, including the dwarf planets Ceres and Pluto, and Saturn’s moon Mimas,” she said. “So there are mechanisms at play that we don’t fully understand. This paper investigates what those could be and how they are relevant to the many bodies in the solar system that could be rich in water but have limited internal heat.”

The study revisited findings from NASA’s Voyager 2 flybys of Uranus in the 1980s and from ground-based observations. The authors created computer models that included additional findings from NASA’s Galileo, Cassini, Dawn, and New Horizons missions (each of which discovered ocean worlds), as well as insights into the chemistry and geology of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Pluto and its moon Charon, and Ceres – all icy bodies around the same size as Uranus’ moons.

The researchers used this modelling to determine how porous the Uranian moons’ surfaces are, finding that they’re likely insulated enough to retain the internal heat required to host an ocean. Additionally, they discovered a potential heat source in the moons’ rocky mantles, which release hot liquid and would help an ocean maintain a warm environment. This scenario is particularly likely for Titania and Oberon, where the oceans may even be warm enough to potentially support habitability.