Overwhelming fear, sweaty palms, shortness of breath, rapid heart rate—these are the symptoms of a panic attack, which people with panic disorder have frequently and unexpectedly. Creating a map of the regions, neurons, and connections in the brain that mediate these panic attacks can provide guidance for developing more effective panic disorder therapeutics.

Now, Salk researchers have begun to construct that map by discovering a brain circuit that mediates panic disorder. This circuit consists of specialized neurons that send and receive a neuropeptide—a small protein that sends messages throughout the brain—called PACAP. What’s more, they determined that PACAP and the neurons that produce its receptor are possible druggable targets for new panic disorder treatments.

The findings were published in Nature Neuroscience on January 4, 2024.

“We’ve been exploring different areas of the brain to understand where panic attacks start,” says senior author Sung Han, associate professor at Salk. “Previously, we thought the amygdala, known as the brain’s fear center, was mainly responsible—but even people who have damage to their amygdala can still experience panic attacks, so we knew we needed to look elsewhere. Now, we’ve found a specific brain circuit outside of the amygdala that is linked to panic attacks and could inspire new panic disorder treatments that differ from current available panic disorder medications that typically target the brain’s serotonin system.”

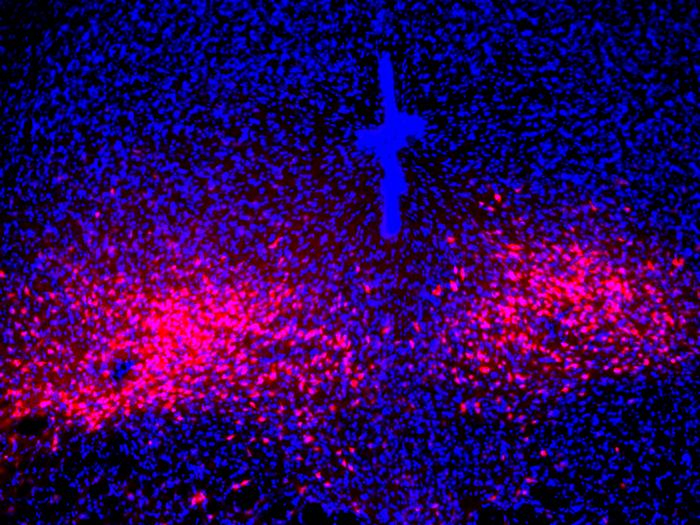

To begin sketching out a panic disorder brain map, the researchers looked at a part of the brain called the lateral parabrachial nucleus (PBL) in the pons (part of the brain stem), which is known as the brain’s alarm center. Interestingly, this small brainstem area also controls breathing, heart rate, and body temperature.

It became evident that the PBL was likely implicated in generating panic and bringing about emotional and physical changes. Furthermore, they found that this brain area produces a neuropeptide, PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide), known as the master regulator of stress responses. But the link between these elements was still unclear, so the team turned to a mouse model of panic attacks to confirm and expand their proposed map.

“Emotional and stress-related behaviors have been associated with PACAP-expressing neurons in the past,” says co-first author Sukjae Kang, senior research associate in Han’s lab. “By mimicking panic attacks in the mice, we were able to watch those neurons’ activity and discover a unique connection between the PACAP brain circuit and panic disorder.”

They found that during a panic attack, PACAP-expressing neurons became activated. Once activated, they release PACAP neuropeptide messenger to another part of the brain called the dorsal raphe, where neurons expressing PACAP receptors reside. The released PACAP messengers activate those receptor neurons, thereby producing panic-associated behavioral and physical symptoms in the mice.

This connection between panic disorder and the PACAP brain circuit was an important step forward for mapping panic disorder in the brain, Han says. The team also found that by inhibiting PACAP signaling, they could disrupt the flow of PACAP neuropeptides and reduce panic symptoms—a promising finding for the future development of panic disorder-specific therapeutics.

According to Han, despite panic disorder’s categorization as an anxiety disorder, there are many ways that anxiety and panic are different—like how panic induces many physical symptoms, like shortness of breath, pounding heartrate, sweating, and nausea, but anxiety does not induce those symptoms. Or how panic attacks are uncontrollable and often spontaneous, while other anxiety disorders, like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are more memory-based and have predictable triggers. These differences, says Han, are why it is critical to construct this panic disorder brain map, so that researchers can create therapeutics specially tailored to panic disorder.

“We found that the activity of PACAP-producing neurons in the brain’s parabrachial nucleus is inhibited during anxiety conditions and traumatic memory events—the mouse’s amygdala actually directly inhibits those neurons,” says Han, who is also the Pioneer Fund Developmental Chair at Salk. “Because anxiety seems to be operating conversely to the panic brain circuit, it would be interesting to look at the interaction between anxiety and panic, since we need to explain now how people with anxiety disorder have a higher tendency to experience panic attack.”

The team is excited to explore PACAP-expressing neurons and PACAP neuropeptides as novel druggable targets for panic disorder. Additionally, they are hoping to further build out their map of panic disorder in the brain to see where the PACAP receptor-producing neurons in the dorsal raphe send their signals, and how other anxiety-related brain areas interact with the PACAP panic system.

Other authors include Jong-Hyun Kim (co-first author), Dong-Il Kim, and Benjamin Roberts of Salk.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (BRAINS grant 1R01MH116203) and the Simons Foundation (Bridge to Independence award SFARI #388708).