A high-tech mineral-mapping effort nearly complete in Afghanistan and the first of its kind in the world already generates $146 million in yearly revenue, and Afghanistan’s minister of mines and petroleum hopes to report $1 billion in revenue by 2020.

The maps were developed using a technology called hyperspectral imaging, which measures visible and near-infrared light reflecting off the Earth’s surface. The results can be used to identify for investors the likely subsurface locations of hydrocarbons like crude oil and natural gas, and minerals like copper, gold, lithium, iron and silver.

“Today is a very important day for geology … because the U.S. Geological Survey is going to hand over 26 boxes of data and maps and they will officially be giving that data to the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan,” Mohammad Akbar Barakzai, the Afghan minister of mines and petroleum, said through a translator.

He spoke here last week at the Embassy of Afghanistan, traveling from Kabul to join officials from the USGS and the Defense Department’s Task Force for Business and Stability Operations.

All three organizations are part of a coalition created by DOD to share American international science and technology as a strategic tool for promoting economic development.

“We can now confidently invite investors to come into Afghanistan and show them where we have potential,” the minister said, adding, “the U.S. Geological Survey, the [Task Force for Business and Stability Operations], the U.S. Agency for International Development, the government of the United States of America — they are helping us out at a very critical time for Afghanistan.”

Barakzai said Afghanistan earns nearly $146 million a year in revenue from its mining sector and by 2020 the projections are that the sector can generate $1 billion a year.

In early March the minister attended the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada conference in Toronto and said he saw great potential for local and foreign investors who seemed quite willing to invest in Afghanistan’s mineral and hydrocarbon sector.

“Especially given the data that was handed over to us today,” Barakzai said, “which is going to help us attract more investment and also show investors specific places where they can invest in different kinds of deposits.”

Joseph Catalino, acting director of the DOD task force, said USGS and TFBSO “have created a fairly remarkable team that has gone from the drawing board to implementation and back again with a number of programs and training in geology and hydrogeology, drilling, processing and identification of minerals.”

TFBSO works with private-sector firms to encourage them to invest in Afghanistan’s mineral and hydrocarbon sectors, Catalino said.

“Big companies, small companies, even really small companies are all asking the same questions — what’s there, where do we look and where do we drill? That’s where this data comes into play,” he added.

“Nothing is guaranteed of course, but the experts here tell me that [hyperspectral imaging] makes wide-area prospecting a thing of the past. … The extractive industries and companies will know more [and] they’ll have to spend less time finding the mineral veins and hydrocarbon pools, which will help stabilize the nation’s economy faster than we projected and … our goal is to help the Afghans stand on their own economically.”

USGS worked in Afghanistan from 1952 to 1973, installing a modern stream-gauge network and a modern seismic station just outside Kabul, USGS Acting Director Dr. Suzette Kimball told the embassy audience.

When USGS returned to Afghanistan in 2003, she said, its scientists began introducing technologies and new ways to assess minerals, water, energy resources and hazards, including satellite remote-sensing platforms, airborne geophysics, airborne hyperspectral imaging, ground geophysics and geospatial and seismic techniques.

“Along the way, in partnership with the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum and the Afghanistan Geological Survey and more than 40 organizations across a 10-year period,” Kimball said, “we have created a 21st-century digital infrastructure for Afghanistan that can be used by the government for planning, developing and implementing many other activities beyond the earth sciences.”

The digital infrastructure will include a modern Afghanistan Geological Survey, a Ministry of Mines and Petroleum data center to store and manipulate the data and a Web-based system to distribute and download data and information, she added.

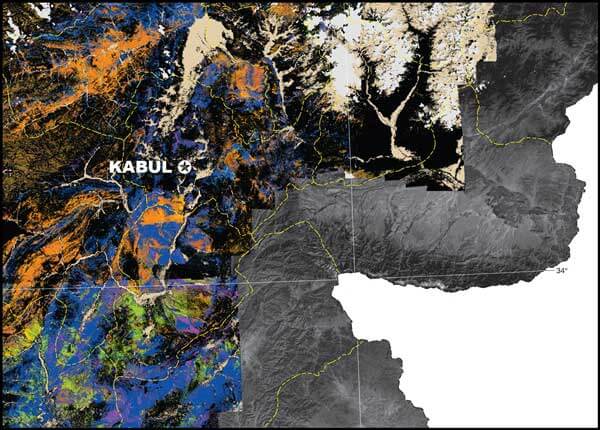

“Today we’re focused on the release of hyperspectral maps that are 1:250,000 scale for 30 quadrangles that cover the entire country of Afghanistan and demonstrate how USGS has used these data and how they can be used in many other geoscience activities within the country,” Kimball said.

Two maps are always produced for each geographic area because the human eye can only see a limited number of colors and the maps contain a vast amount of information.

One is a surface map showing 30 quadrangles of carbonates, phyllosilicates, sulfates, altered minerals and other materials. The other is a surface map showing 30 quadrangles of iron-bearing minerals and other materials, so 60 quadrangle maps at the 1:250,000 scale were transferred to the Afghans.

For humans, the visible spectrum is a very limited band of light, she explained, but hyperspectral technology lets people see information across a much wider spectrum.

“In this case we’re looking at something greater than 200 bands that allows us to be able to analyze information at a very fine and precise resolution,” Kimball added. “It allows us to see that each of the mineral characteristics has a unique fingerprint and therefore can be analyzed and visualized within this dataset.”

This is the first hyperspectral survey of an entire country, the USGS director said, adding that it represents the single largest volume of imaging spectroscopy data collection by any agency or organization on Earth.

“So it is in fact a very special dataset that we transmit today,” she said, “and we’re very proud to do so.”

In her discussion of the datasets, Dr. Trude King, a Denver-based USGS research geophysicist and lead for the Afghanistan hyperspectral data project, said data for the country map was collected in 2007.

That year, from Aug. 22 to Oct. 2, NASA contributed its high-altitude, long-range WB-57 aircraft to fly the HyVista Corp. hyperspectral instrument over Afghanistan for USGS, capturing more than 70 percent of the country’s rugged surface.

“We collected the data in 2007, our full country maps were ready and available in 2008, and since then we’ve been looking at the data, checking the data and verifying the data because we want to be careful about what we release, and today we have rolled out the 1:250,000-scale quads.

In 2009, USGS and the DOD task force began working closely to help get the hyperspectral data into a format mining companies could use to evaluate opportunities in Afghanistan’s mineral and gas sector.

At the embassy King stood before the audience and showed slides of the hyperspectral maps.

“This is the first whole-country map of Afghanistan. We’d never seen one before … you can see huge regional-scale tectonic structures and geologic processes … This is the iron-bearing map of the full country. We’ve put on top of that some of the major faults and you can see how we’re mapping tectonic boundaries, geologic boundaries,” she told the audience.

“We don’t have full coverage of the country because of … security reasons, but we think with this data we have helped transition Afghan’s natural resources sector into the 21st century,” King added. “We think it has helped accelerate the exploration, the commercialization, and improved the economic security of Afghanistan. So it’s been a pleasure.”

Scientists at USGS have learned much by working with and helping the Afghan geologists, she said. The U.S. scientists have learned how to handle large datasets and process data in a more timely fashion, and the Afghan mineral resources have given them a new perspective on geological processes.

“We used an early NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory sensor in the mid-1980s. We started working with the data and progressed up so we could handle large datasets that we could map on more accurate standards because these are all compared to standards that we’ve developed — our spectral libraries for comparison,” King explained.

“We do a lot of the processing that needs to be done before we get to this map stage — removing atmospheric absorption and other things before we can have a clean dataset to work with. That’s called calibration. And then we map,” she said.

King said the USGS is preparing to do a large survey in Alaska that may not have been possible if the scientists hadn’t learned some of the techniques and processes they learned in Afghanistan.

“It gave us the opportunity to develop software, develop new calibration methods, it gave us rapid mapping — we adapted the mapping algorithms that had been written for the Afghans for our use,” she said, “so the USGS has benefited immensely.”