Would you lie on your income tax return to save money for your struggling family? Moral judgment calls like this one help weave the fabric of a civilized society.

Everyone knows you shouldn’t cheat on your taxes. However, people don’t always make the correct decision about right and wrong. Atypical moral development is associated with antisocial and criminal behaviors, creating an immense burden on society with an estimated cost of over $1 trillion annually in the United States.

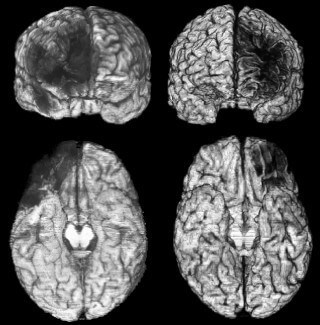

A new University of Iowa study, published in the April edition of Brain, suggests that the brain’s ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is critical for the acquisition and maturation of moral competency—going beyond self-interest to consider the welfare of others.

Researchers found that patients who suffered vmPFC damage early in life, unlike patients in whom the brain injury occurred during adulthood, endorsed significantly more self-serving judgments that broke moral rules or inflicted harm on others. For example, one person who had suffered damage to the vmPFC early in childhood said that it would be fine to lie on THEIR resume or to harm their annoying boss.

“By understanding how dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex early in life disrupts moral development, we hope to inform efforts to treat and prevent antisocial behavior, from common criminality to the mass murders our society has witnessed in recent years,” says co-first author Bradley Taber-Thomas, postdoctoral fellow in psychology at Penn State University who earned his doctorate in neuroscience at the UI in 2011.

“It’s imperative that we find ways to promote the development of social-emotional brain systems to encourage healthy, adaptive social development from an early age.”

Examinations of patients with early-onset brain injuries can reveal whether particular brain areas and circuits are necessary for the acquisition and maturation of particular moral faculties.

“This parallels the behavior of persons with psychopathy. The typical psychopath, however, doesn’t have the same brain damage—in fact, their brains look entirely normal in a CT scan or MRI study,” says Daniel Tranel, senior author and professor of neurology and psychology at the UI. “Is the cause of psychopathy genetic, environmental, or some combination? Can psychopathy be cured with medications or behavioral therapy? This research paper is relevant to these questions.”

Looking inside the brain

To conduct this study, the UI team recruited patients from the Iowa Neurological Patient Registry who had suffered damage to the vmPFC at age 16 years or younger. For comparison, the team also examined a group of individuals who early in life developed brain damage outside the vmPFC that did not significantly intrude on other emotion-processing structures like the amygdala and insula.

In the experiment, participants made judgments on 50 hypothetical scenarios. After each scenario, a Yes/No question about a hypothetical action was presented. For example, “Would you … in order to …?”

Each of the moral scenarios presented to the patients fell into one of two categories: high conflict or low conflict. In high-conflict scenarios, the options present competing social-emotional (personal) and utilitarian considerations (e.g., smothering a crying baby to save a group of people). In low-conflict scenarios, at least one of those conflicting considerations is absent.

The low-conflict scenarios are further subdivided into two categories: self-serving scenarios and utilitarian scenarios. Self-serving scenarios (e.g., harming an annoying boss) probe the integrity of moral development by pitting a self-serving action against a moral rule. Utilitarian scenarios (e.g., lying to save others from physical harm) pit a utilitarian principle against impersonal harm.

Moral development and the vmPFC

The data shows that individuals with developmental-onset vmPFC injury (D-vmPFC) were significantly more likely to endorse the low-conflict self-serving action than all other groups. For nonmoral and low-conflict utilitarian scenarios, there were no significant differences between the D-vmPFC group and all other groups.

“This shows that vmPFC dysfunction does not disrupt all types of judgments, or even moral judgment in general,” Taber-Thomas says. “The disruption is specific to circumstances where self-interest is pitted against the welfare of others.”

The researchers also found that the earlier in life the vmPFC damage occurred the higher the likelihood of endorsing low-conflict self-serving actions. Patients with the earliest onset (prior to age 5) exhibited the greatest endorsement of such actions and patients with onset during school-age years (ages 8 to 17) had the next-greatest endorsement. Patients with onset in adulthood (ages 30 to 60) had the lowest endorsement of such actions, and were actually similar to healthy participants in rarely endorsing such actions.

These findings suggest that the vmPFC enables children to learn that self-serving actions are aversive based on early life experiences. For example, when a child grabs a toy from another child, he/she receives feedback from the other child, and perhaps a parent or teacher.

“Once the basic rules are laid down, moral judgments about situations involving basic self-interest are not susceptible to vmPFC damage later in life,” says co-first author Erik Asp, postdoctoral scholar in psychiatry who earned a doctorate in neuroscience at the UI in 2012. “Brain injuries acquired earlier in life often give more time to recover and result in less severe impairments, but our study suggests this may not be the case in the vmPFC, where earlier damage resulted in more severe disruption to moral judgment.”

Additionally, vmPFC patients exhibited a higher endorsement of high-conflict scenarios compared to the comparison groups.

Since D-vmPFC patients endorsed a utilitarian action for the vast majority of the low-conflict utilitarian actions suggests that they appreciate others’ welfare. Thus, their impairment seems to be in weighing that welfare against their own self-interest.

“Patients with adult-onset vmPFC damage functioned normally, while early-onset patients have a much higher rate of endorsement of these self-serving behaviors,” Tranel says. “Is it okay to cheat on your taxes? The patients who sustained damage to the vmPFC early in life chose this option. This parallels what shows up in patients with psychopathy.”

The research was supported by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA022549) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (P01 NS19632).

In addition to Tranel, Taber-Thomas, and Asp, the research team included Steven Anderson, UI associate professor of neurology; Matthew Sutterer, UI doctoral student in neuroscience; and Michael Koenigs, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.