The mutations were familiar, but the patients’ conditions seemed baffling at first. A team lead by Rockefeller University researchers had linked variations in an immune gene to rare bacterial infections. Shortly afterward, Chinese scientists told them of three children in that country with mutated versions of the same gene. However, the Chinese children had no history of the severe bacterial infections. Instead, they had seizures and unusual calcium deposits deep in their brains.

This discrepancy led to the discovery of an immune protein with paradoxical roles: It both aids and tamps down aspects of an immune system response, according to research conducted in Jean-Laurent Casanova’s St. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases at Rockefeller in collaboration with scientists in China and elsewhere. The team’s report was published today (October 12) in Nature.

“It has turned out that mutations in a single gene eliminate the immune protein ISG15, giving rise to two different problems: an inability to resolve harmful inflammation, which can lead to autoimmune disease, and susceptibility to infections caused by the tuberculosis bacterium and its cousins,” Casanova says. “By identifying the source of this genetic disorder, we have taken a first step toward finding treatments for those facing the autoimmune disease and severe TB-related infections it may produce.”

When under attack, the immune system releases signaling proteins known as interferons, which further activate the body’s defenses. In previous research, Dusan Bogunovic, a former postdoc in the lab now an Assistant Professor at the Department of Microbiology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, linked a lack of ISG15 to an unusual vulnerability to infections by mycobacteria, a group of common bacteria that include the TB bug. He and colleagues found three children, one from Turkey, two from Iran, who became severely ill after receiving the anti-tuberculosis BCG vaccine. Normally, ISG15 protects against infection by mycobacteria by prompting the release of type 2 interferon, but all three children had two copies of a defective form of the ISG15 gene, and became infected by a TB-related component of the vaccine.

After this discovery, ISG15’s story continued to unfold. Bogunovic and his colleagues reported this link, and then scientists in China reached out saying they had also seen loss-of-function mutations in three patients, all from a single family. But none of these three had had unexplained mycobacterial infections, such as those caused by the vaccine.

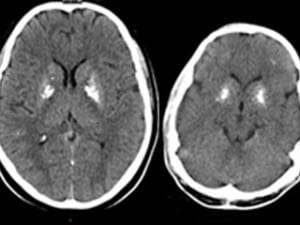

“We asked, why were they patients?” Bogunovic recalls. “Our Chinese colleagues said these kids had seizures; in fact, one child had died from them. When we looked into their BCG vaccination history, we found these children, who were born at home in a remote village, never received their shots, so they never became sick. Next we looked back at our first set of patients. None of them had ever had seizures, but we performed brain scans that found abnormal calcium deposits in a deep part of the brain involved in controlling movement — just like the deposits in brains of the Chinese children.”

The researchers recognized the calcium deposits as a feature of a group of autoinflammatory diseases, including the neurodevelopmental disorder Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. These are thought to occur when type 1 interferon, which normally helps fight viral infections, runs amok, triggering harmful and unnecessary inflammation, leading to disease. When Bogunovic and his colleagues then looked for evidence something similar was happening to the six patients, they found unusually high expression of genes stimulated by type 1 interferon.

Using cells from the patients, the researchers found that when they restored the ISG15 gene, the cells became able to resolve the inflammation. Further experiments performed in collaboration with Sandra Pellegrini at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, revealed the mechanics that linked a lack of ISG15 with an increase in type 1 interferon signaling: Under normal conditions, ISG15 prevents the degradation of another protein, USP18, which is responsible for turning down the dial on type 1 interferon. With no ISG15, and as a result, little USP18, interferon becomes too active.

The six children all showed elevated levels of autoantibodies, immune proteins that mistakenly attack the body itself, suggesting that in time they will likely develop autoimmune disease. “However, with this knowledge, we hope they can monitor and properly treat this condition, just as they know now to avoid the BCG vaccine and other possible sources of mycobacterial infection,” Bogunovic says. “Ultimately, ISG15 deficits may be included in genetic screening tests for infants to make early detection widely available. No treatments exist for many autoimmune disorders, but our work advances our understanding of them, and, as a result, the prospects for finding cures.”