Scientists at the National Institutes of Health have solved a long-standing mystery about the origin of one of the cell types that make up the ovary. The team also discovered how ovarian cells share information during development of an ovarian follicle, which holds the maturing egg. Researchers believe this new information on basic ovarian biology will help them better understand the cause of ovarian disorders, such as premature ovarian failure and polycystic ovarian syndrome, conditions that both result in hormone imbalances and infertility in women.

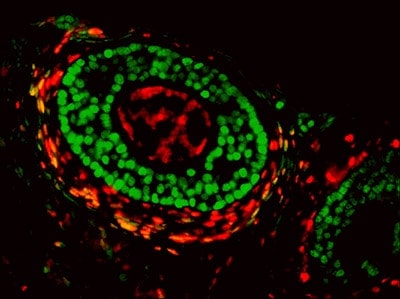

Researchers at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), part of NIH, published the findings online April 28 in the journal Nature Communications. According to NIEHS researcher and corresponding author Humphrey Yao, Ph.D., the ovarian follicle is the basic functional unit of the ovary, which contains the egg surrounded by two distinct cell types, known as granulosa cells and theca cells. Yao said scientists had known the cellular origins of the egg and granulosa cells, but did not know where theca cells came from or what directed their development.

“The answer to this question remained unanswered for decades, but using a technique called lineage tracing, we determined that theca cells in mice come from both inside and outside the ovary, from embryonic tissue called mesenchyme,” Yao said. “We don’t know why theca cells have two sources, but it tells us something important — a single cell type may actually be made up of different groups of cells.”

Without theca cells, women are unable to produce the hormones that sustain follicle growth, he continued. One of the major hormones theca cells produce is androgen, which is widely thought of as a male hormone. But, in a superb example of teamwork, the granulosa cells convert the androgen to estrogen.

As a result of their work, Yao and his colleagues uncovered the molecular signaling system that enables theca cells to make androgen. This communication pathway is derived from granulosa cells and another structure in the ovary called the oocyte, or immature egg cell. The crosstalk between the egg, granulosa cells, and theca cells was an unexpected finding, but one that may provide insight into how ovarian disorders arise.

“The problem starts within the theca cell compartment,” said Chang Liu, Ph.D., a visiting fellow in Yao’s group and first author on the paper. “Now that we know what makes these cells grow, we can search for possible genetic mutations or environmental factors that affect the process leading to ovarian cell disorders.”

For future work, Yao wants to explore the two types of cells that make up theca cells. Since the research has been carried out in mice, Yao will have to determine if the same holds true for humans, but the research may potentially uncover several roles theca cells play in female fertility.