University of Illinois at Chicago physicians have cured 12 adult patients of sickle cell disease using stem cell transplantation from healthy, tissue-matched siblings.

The transplants at UI Health were the first performed outside the National Institutes of Health campus in Maryland, where the procedure was developed.

Because the technique eliminates the need for chemotherapy to prepare the patient to receive the transplanted cells, it offers the prospect of a cure for tens of thousands of adults with sickle cell disease.

About 90 percent of the approximately 450 patients who have received stem cell transplants for sickle cell disease have been children. Chemotherapy was considered too risky for adult patients, who are often more weakened than children by the disease.

“Adults with sickle cell disease are now living on average until about age 50 with blood transfusions and drugs to help with pain crises, but their quality of life can be very low,” says Damiano Rondelli, chief of hematology/oncology and director of the blood and marrow transplant program at UI Health.

“Now, with this chemotherapy-free transplant, we are curing adults with sickle cell disease, and we see that their quality of life improves vastly within just one month of the transplant,” said Rondelli, Michael Reese professor of hematology in the College of Medicine. “They are able to go back to school, go back to work, and can experience life without pain.”

About 1 in every 500 African Americans in U.S. have sickle cell disease

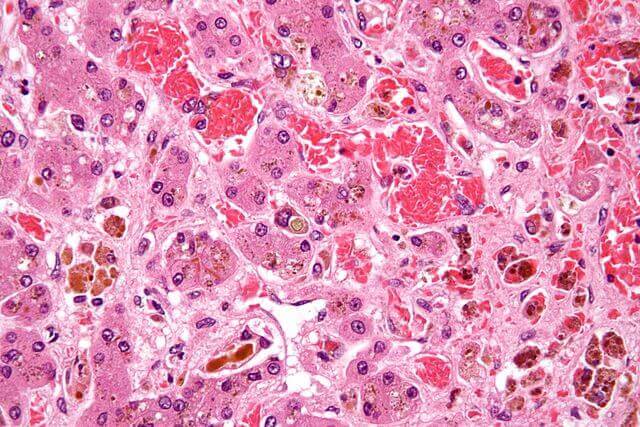

Sickle cell disease is inherited. It primarily affects people of African descent, including about one in every 500 African Americans born in the U.S. The defect causes the oxygen-carrying red blood cells to be crescent shaped, like a sickle. The misshapen cells deliver less oxygen to the body’s tissues, causing severe pain and, eventually, stroke or organ damage.

Doctors have known for some time that bone marrow transplantation from a healthy donor can cure sickle cell disease. But few adults received transplants because high-dose chemotherapy was needed to kill off the patients’ own blood-forming cells — and their entire immune system — to prevent rejection of the transplanted cells, leaving patients open to infection.

In the new procedure, patients receive immunosuppressive drugs just before the transplant, along with a very low dose of total body irradiation, a treatment much less harsh and with fewer potentially serious side effects than chemotherapy.

Next, donor cells from a healthy and tissue-matched sibling are transfused into the patient. Stem cells from the donor produce healthy new blood cells in the patient, eventually in sufficient quantity to eliminate symptoms. In many cases, sickle cells can no longer be detected. Patients must continue to take immunosuppressant drugs for at least a year.

In the reported trial, published online in the journal Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation, UIC physicians transplanted 13 patients, 17 to 40 years of age, with a stem cell preparation from the blood of a tissue-matched sibling. In a further advance of the NIH procedure, the physicians successfully transplanted two patients with cells from siblings who matched but had a different blood type.

One year later, improved health

In all 13 patients, the transplanted cells successfully took up residence in the marrow and produced healthy red blood cells. One patient who failed to follow the post-transplant therapy reverted to the original sickle cell condition.

None of the patients experienced graft-versus-host disease, a condition where immune cells originating from the donor attack the recipient’s body.

One year after transplantation, the 12 successfully transplanted patients had normal hemoglobin concentrations in their blood and better cardiopulmonary function. They reported less pain and improved health and vitality.

Four of the patients stopped post-transplantation immunotherapy without transplant rejection or other complications.

“Adults with sickle cell disease can be cured without chemotherapy — the main barrier that has stood in the way for them for so long,” Rondelli said. “Our data provide more support that this therapy is safe and effective and prevents patients from living shortened lives, condemned to pain and progressive complications.”