Warming ocean temperatures a third of a mile below the surface, in a dark ocean in areas with little marine life, might attract scant attention. But this is precisely the depth where frozen pockets of methane ‘ice’ transition from a dormant solid to a powerful greenhouse gas.

New University of Washington research suggests that subsurface warming could be causing more methane gas to bubble up off the Washington and Oregon coast.

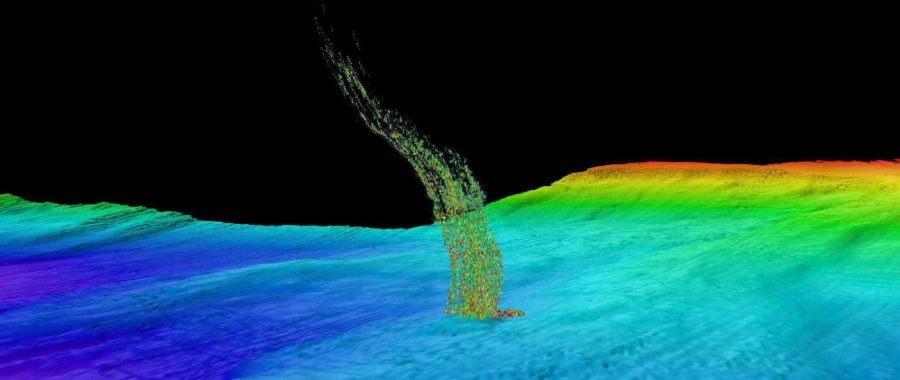

The study, to appear in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, shows that of 168 bubble plumes observed within the past decade a disproportionate number were seen at a critical depth for the stability of methane hydrates.

The new study looks for evidence of bubble plumes off the coast, including observations by UW research cruises, earlier scientific studies and local fishermen’s reports. The authors included bubble plumes that rose at least 150 meters (490 feet) tall that clearly originate from the seafloor. The dataset included 45 plumes originally detected by fishing boats, whose modern sonars can detect the bubbles while looking for schools of fish, with their observations later confirmed during UW research cruises.

Results show that methane gas is slowly released at almost all depths along the Washington and Oregon coastal margin. But the plumes are significantly more common at the critical depth of 500 meters, where hydrate would decompose due to seawater warming.

“What we’re seeing is possible confirmation of what we predicted from the water temperatures: Methane hydrate appears to be decomposing and releasing a lot of gas,” Johnson said. “If you look systematically, the location on the margin where you’re getting the largest number of methane plumes per square meter, it is right at that critical depth of 500 meters.”

Still unknown, however, is whether these plumes are really from the dissociation of frozen methane deposits.

“The results are consistent with the hypothesis that modern bottom-water warming is causing the limit of methane hydrate stability to move downslope, but it’s not proof that the hydrate is dissociating,” said co-author Evan Solomon, a UW associate professor of oceanography.

Solomon is now analyzing the chemical composition of samples from bubble plumes emitted by sediments along the Washington coast at about 500 meters deep. Results will confirm whether the gas originates from methane hydrates rather than from some other source, such as the passive migration of methane from deeper reservoirs to the seafloor, which causes most of the other bubble plumes on the continental margin.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy. Other co-authors are Marie Salmi, a UW doctoral student in oceanography with Johnson, and Una Miller, a former UW undergraduate who is now a research assistant in Johnson’s group. Miller will present the results at the American Geophysical Union’s annual fall meeting in San Francisco.