A mother’s body transforms in numerous ways during pregnancy, but some changes remain long after giving birth. Researchers at London’s Francis Crick Institute have discovered that pregnancy permanently alters the small intestine in mice, potentially preparing the body for future pregnancies and offering new insights into how organs adapt to life’s challenges.

The study, published Wednesday in Cell, reveals that a mouse’s small intestine grows 18% longer by the end of pregnancy and, surprisingly, never fully returns to its pre-pregnancy size – even after the mouse is done nursing.

This discovery marks one of the first detailed investigations into how pregnancy affects the digestive system at the molecular and cellular level, potentially adding to our understanding of metabolic changes during human pregnancy.

“We don’t often think about organs changing size or appearance in response to triggers in adulthood rather than earlier childhood and adolescent development, but the gut is a striking example of how the body responds to a new challenge at different stages of life, in this case pregnancy,” said Irene Miguel-Aliaga, Group Leader of the Organ Development and Physiology Laboratory at the Crick.

The researchers found that a pregnant mouse’s small intestine begins to elongate just seven days into pregnancy. By day 18 (near the end of mouse gestation), the intestine had grown almost one-fifth longer than before pregnancy.

What makes this finding particularly intriguing is that the intestine remains longer even after the mice finish nursing their pups – a change that persists for at least 35 days after weaning. The researchers also observed that the intestine grows even longer during a second pregnancy compared to the first.

Two-Part Transformation

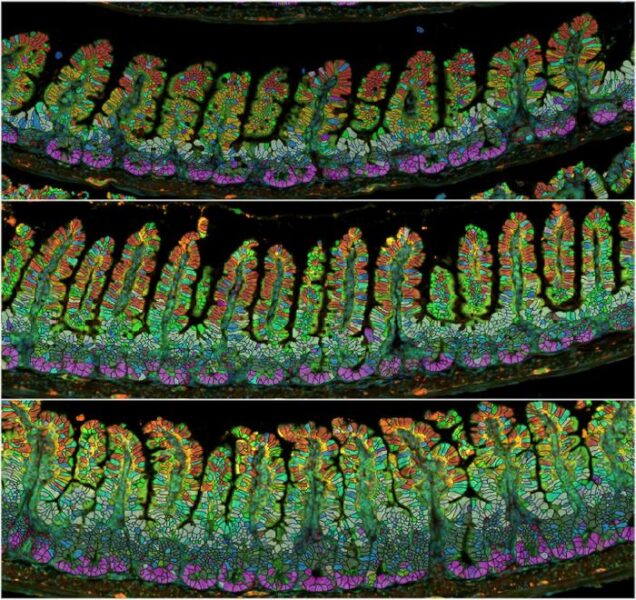

The study identified two distinct types of changes in the intestine: the overall lengthening of the organ and changes to its internal structures.

Inside the small intestine, finger-like projections called villi (which absorb nutrients) and invaginations called crypts (where cells supplying the villi are produced) also undergo significant changes. Both structures grow alongside the lengthening intestine during pregnancy, but unlike the permanent increase in intestine length, these internal structures return to their pre-pregnancy state within a week after weaning.

The researchers believe these adaptations likely enhance nutrient absorption, helping the mother support both herself and her offspring during pregnancy and nursing.

To understand what drives these changes, the team dug deeper into the cellular and molecular mechanisms at work.

A Cellular Surge

The team discovered that the precursors of intestinal epithelial cells multiply rapidly during early pregnancy, with newly generated cells migrating faster up the villi. These pregnancy-triggered effects persist through birth and nursing but revert to pre-pregnancy rates just a week after weaning.

By analyzing which genes were activated during pregnancy, the researchers identified significant changes in enterocytes – nutrient-absorbing cells in the villi. These changes primarily related to increased metabolic activity.

One particularly interesting finding was the early increase in a membrane protein called SGLT3a. Unlike related proteins that sense glucose levels, SGLT3a responds to sodium and protons. The researchers found that this protein was responsible for about 45% of the villi growth triggered by pregnancy.

In a revealing experiment, the team found that simply supplementing the diet of female mice with sodium induced villi growth even in mice that had never been pregnant.

Hormonal Influences

The researchers observed that even “pseudo-pregnant” mice – females whose pregnancy hormone levels increased after mating with sterile males – still showed some intestinal changes. This suggests that hormones triggered by reproduction may play an important role in initiating these adaptations.

The findings add to our understanding of how female biology adapts to the demands of reproduction, revealing sophisticated mechanisms that balance energy usage with reproductive success.

“The presence of reversible and non-reversible changes may reflect a trade-off in energy,” Miguel-Aliaga explained. “Maintaining a longer gut after a first pregnancy might ‘prime’ the body for a second, while reducing villi length back to normal might stop excessive absorption from food while it’s unnecessary.”

From Mice to Humans

While this research was conducted in mice, it raises interesting questions about whether similar changes might occur in humans.

“Understanding how pregnancy impacts the body in other mammals is a critical first step to understanding this in people,” said Tomotsune Ameku, former postdoctoral researcher at the Crick, now Assistant Professor at Science Tokyo and first author of the study.

“We don’t fully understand why the gut expands in response to pregnancy, but we think it must give an evolutionary advantage and help mice reproduce regularly,” Ameku added.

The researchers noted that modern human lifestyles may change how these adaptations function. “We’re generally eating more and reproducing less than we used to, so intestine growth might not be as useful anymore,” Ameku observed.

The research team is now investigating whether other cell types in the mouse intestine also undergo remodeling during pregnancy, and whether similar changes occur in humans. They plan to examine gut length in people who have and haven’t had children to see if comparable adaptations exist in human biology.

This study adds to growing evidence that reproductive events can have lasting impacts on female physiology beyond the reproductive system itself – insights that may eventually help us better understand and address women’s health issues related to metabolism and digestion.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!