Most people in the United States probably would agree that priorities and values can vary greatly from region to region and even state to state. Although these differences have largely been characterized along political lines, little has been understood about why this cultural regionalism exists and exactly how it impacts national dialogues and policy decisions.

Why for example, is illicit substance use greater in states like Hawaii and New Hampshire relative to Mississippi and Ohio, but incidents of discrimination much higher in the latter than the former? Why do states like Colorado and Connecticut score low on trait conscientiousness—a characteristic associated with greater self-constraint and conformity—and high on trait openness—a characteristic associated with greater tolerance and non-traditional values—relative to states like Alabama and Kansas, which exhibit the opposite pattern? Why do some states such as Oregon and Vermont exhibit high levels of creativity, whereas other states, such as Kentucky and North Dakota, do not?

For the first time, a group of University of Maryland researchers has discovered a parsimonious explanation—one both simpler and deeper than politics. States differ systematically on whether they are “tight”—have strong norms and little tolerance for deviance—or are “loose”—have weak norms and high tolerance for deviance.

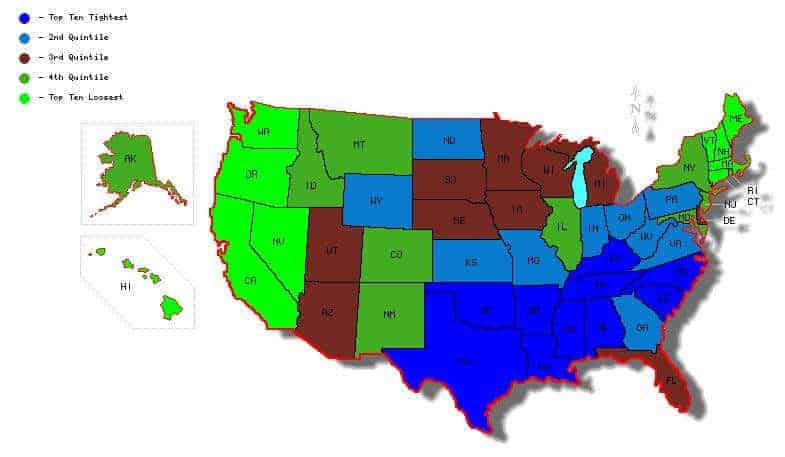

Loose states are found primarily in the North East, the West Coast, and include some Mountain states, while tight states are primarily in the South and parts of the Midwest. This distinction “goes far beyond the typical red state versus blue state dichotomy. Our unique study shows there is a quantifiable principle that can account for a large swath of state differences in ecological and human-made conditions, personality characteristics, and various state outcomes,” said UMD Professor of Psychology Michele J. Gelfand, who, along with graduate student Jesse R. Harrington, wrote the study that will appear in a new issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The authors not only document whether states are tight or loose (see figure below), but also provide an explanation: state tightness-looseness is highly associated with how much ecological and historical threat they have faced. Tight states tend to have higher rates of natural disasters, greater environmental vulnerabilities, fewer resources, and greater incidence of disease. States without these threats can “afford” more deviant behavior, the authors conclude.

“This suggests that tightness is at least in part a reaction to ecological and historical factors; strong social norms develop to coordinate individuals and protect against threatening environments. Importantly, these same relationships were previously found between nations,” said Gelfand, who in 2011 led an international research team that was the first to investigate how “tightness” and “looseness” applied to global cultures, examining responses from 7,000 people across 33 nations. The team developed a measure for these 33 countries, which was published in Science.

Tightness-looseness also relates to average state “personality.” Individuals in tighter states tend to exhibit higher “conscientiousness”—a trait associated with greater impulse control, conformity to social norms and self-constraint. Looseness is associated with higher “openness”—a trait associated with greater tolerance and curiosity, non-traditional values and beliefs, and preference for originality.

“There are pros and cons related to each side of the tightness-looseness continuum. Tight states tend to be more socially stable, orderly and exhibit more personal self-control—yet tightness is also linked to higher incarceration rates, greater discrimination, lower creativity, and lower happiness,” Harrington said. “Loose states tend to be more creative, have greater equality and tolerance, and be happier. But they also exhibit higher drug and alcohol abuse and greater social instability.”

As with the previous international study, Gelfand said she and Harrington hope that their new research on tightness and looseness across the 50 states will ultimately inform national conversations and policy decisions on critical topics.

“A better understanding of the cultural variation across the 50 states is critical to improving communication, cooperation, and progress when it comes to making decisions that affect our nation,” Gelfand said. “The challenges we face as a nation require cooperation if we want real change. This research might help us understand why we differ and to help us to develop common ground.” The full study is available here.