What if all the energy needed by society existed just a mile or two above our heads? That’s the question raised by researchers in an emerging field known as airborne wind energy, which envisions using devices that might look like parachutes or gliders to capture electricity from the strong, steady winds that blow well above the surface in certain regions.

While logistical challenges and environmental questions remain, scientists at NCAR, the University of Delaware, and the energy firm Garrad Hassan have begun examining where the strongest winds are and how much electricity they might be able to generate.

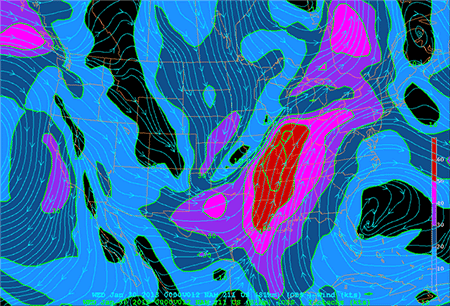

Their key finding: winds that blow from the surface to a height of 3,000 meters (nearly 10,000 feet) appear to offer the potential to generate more than 7.5 terawatts—more than triple the average global electricity demand of 2.4 terawatts (as of 2012, according to the study). Among the areas where such winds are strongest: the U.S. Great Plains, coastal regions along the Horn of Africa, and large stretches of the tropical oceans.

This type of research could prove critical if airborne wind energy takes off. The growing industry now includes more than 20 startups worldwide, exploring various designs for devices that could be tethered to ground stations and then raised or lowered to capture the most suitable winds at any point in time.

“From an engineering point of view, this is really complicated,” said NCAR scientist Luca Delle Monache, a co-author of a new study examining these issues. “But it could greatly increase the use of renewable energy and move the U.S. toward the goal of energy independence.”

To estimate the potential of airborne wind energy, Delle Monache, with Cristina Archer at the University of Delaware and Daran Rife at Garrad Hassan, turned to an NCAR data set known as Climate Four Dimensional Data Assimilation. It blends computer modeling and measurements to create a retrospective analysis of the hourly, three-dimensional global atmosphere for the years 1985–2005.

The research team looked for various types of wind speed maxima, including recurring features known as low-level jets. Such jets can be ideal for energy because their speed and density is as high or higher than jets at higher elevations that would be beyond the reach of tethered wind devices. They also blow more steadily than winds captured by conventional wind turbines near the surface, potentially offering a more reliable source of energy.

Low-level jets blowing at 30-50 miles per hour or more can be found at several locations worldwide, often close to mountainous terrain or to persistent atmospheric features that help focus and channel wind. One of the strongest low-level jets on Earth flows from the Gulf of Mexico north across the Great Plains.

A study by the scientists, published last month in Renewable Energy, focused on winds in January and July. The team is now looking for additional funding to provide a more complete picture of the potential of higher-level winds. Their main goals are to estimate the strength of the winds year round and to build an interface that would enable users to explore the strength of the winds over specific regions.

“It’s important to understand the magnitude of this resource and what might be possible,” Delle Monache said.