New research shows that more than four billion years ago, the surface of Earth was heavily reprocessed – or mixed, buried and melted – as a result of giant asteroid impacts. A new terrestrial bombardment model based on existing lunar and terrestrial data sheds light on the role asteroid bombardments played in the geological evolution of the uppermost layers of the Hadean Earth (approximately 4 to 4.5 billion years ago).

An international team of researchers published their findings in the July 31, 2014 issue of Nature.

“When we look at the present day, we have a very high fidelity timeline over the last about 500 million years of what’s happened on Earth, and we have a pretty good understanding that plate tectonics and volcanism and all these kinds of processes have happened more or less the same way over the last couple of billion years,” says Lindy Elkins-Tanton, director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University.

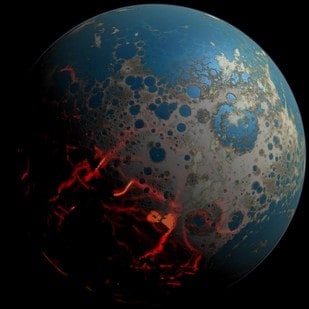

But, in the very beginning of Earth’s formation, the first 500 million years, there’s a less well-known period which has typically been called the Hadean (meaning hell-like) because it was assumed that it was wildly hot and volcanic and everything was covered with magma – completely unlike the present day.

Terrestrial planet formation models indicate Earth went through a sequence of major growth phases: accretion of planetesimals and planetary embryos over many tens of millions of years; a giant impact that led to the formation of our moon; and then the late bombardment, when giant asteroids, dwarfing the one that presumably killed the dinosaurs, periodically hit ancient Earth.

While researchers estimate accretion during late bombardment contributed less than one percent of Earth’s present-day mass, giant asteroid impacts still had a profound effect on the geological evolution of early Earth. Prior to four billion years ago, Earth was resurfaced over and over by voluminous impact-generated melt. Furthermore, large collisions as late as about four billion years ago may have repeatedly boiled away existing oceans into steamy atmospheres. Despite heavy bombardment, the findings are compatible with the claim of liquid water on Earth’s surface as early as about 4.3 billion years ago, based on geochemical data.

A key part of Earth’s mysterious infancy period that has not been well quantified in the past is the kind of impacts Earth was experiencing at the end of accretion. How big and how frequent were those incoming bombardments, and what were their effects on the surface of the Earth? How much did they affect the ability of the now cooling crust to actually form plates and start to subduct and make plate tectonics? What kind of volcanism did it produce that was different from volcanoes today?”

“We are increasingly understanding both the similarities and the differences to present day Earth conditions and plate tectonics,” says Elkins-Tanton. “And this study is a major step in that direction, trying to bridge that time from the last giant accretionary impact that largely completed the Earth and produced the moon, to the point where we have something like today’s plate tectonics and habitable surface.”

The new research reveals that asteroidal collisions not only severely altered the geology of the Hadean Earth, but likely played a major role in the subsequent evolution of life on Earth as well.

“Prior to approximately four billion years ago, no large region of Earth’s surface could have survived untouched by impacts and their effects,” says Simone Marchi of NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute at the Southwest Research Institute. “The new picture of the Hadean Earth emerging from this work has important implications for its habitability.”

Large impacts had particularly severe effects on existing ecosystems. Researchers found that on average, Hadean Earth could have been hit by one to four impactors that were more than 600 miles wide and capable of global sterilization, and by three to seven impactors more than 300 miles wide and capable of global ocean vaporization.

“During this time, the lag between major collisions was long enough to allow intervals of more clement conditions, at least on a local scale,” says Marchi. “Any life emerging during the Hadean eon was likely resistant to high temperatures, and could have survived such a violent period in Earth’s history by thriving in niches deep underground or in the ocean’s crust.”