Failing to find a mating partner is a dent to the reproductive prospects of any animal, but in the flatworm species Macrostomum hystrix it might involve a real headache. Zoologists from the Universities of Basel and Bielefeld have discovered the extraordinary lengths to which this animal is willing to go in order to reproduce – including apparently injecting sperm directly into their own heads. The academic journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B has published their findings.

The absence of a mate usually spells disaster for sexually reproducing animals. However, some simultaneous hermaphrodites – animals who have both male and female sex organs at the same time – have developed an escape route for this scenario: self-fertilization. It is an imperfect solution, as any offspring produced by so-called “selfing” are bound to be inbred, but still better than not reproducing at all.

In previous studies, it had been established that the flatworm species Macrostomum hystrix is capable of switching to just such selfing behavior when isolated from mating partners, a behavior found in many but not all simultaneous hermaphrodites. In their new study, Dr. Lukas Schärer from the University of Basel and his team now show the bizarre, yet remarkable mechanisms Macrostomum hystrix has developed that make this possible.

A shot to the head

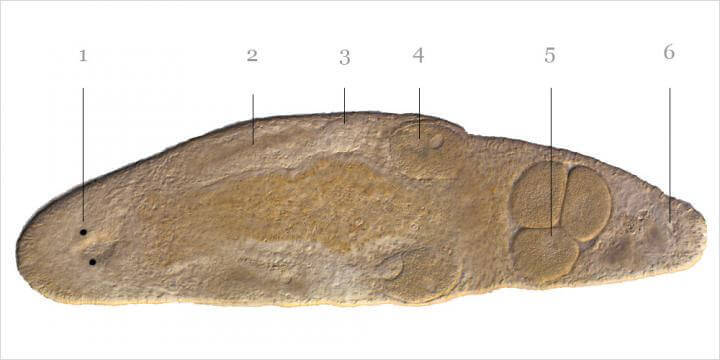

The studied flatworms are highly transparent and their insides can therefore be easily observed under the microscope. By doing so, the zoologists discovered that under selfing conditions, when hermaphroditic individuals had to use their own sperm to fertilize their own eggs, the worms had very few sperm in their tail region. This is in stark contrast to worms kept in a group, which contained most sperm in their tails, close to where fertilization actually occurs. Instead, isolated worms had more sperm in their head region.

This implies a rather strange insemination route: by using its needle-like male copulatory organ, an isolated worm can self-inject sperm into its own anterior body, from where the sperm then moves through the body towards the eggs. “As far as we know, this is the first described example of hypodermic self-injection of sperm into the head. To us this sounds traumatic, but to these flatworms it may be their best bet if they cannot find a mate but still want to reproduce” explains Dr. Steven Ramm, first-author of the study. Such a convoluted route is likely needed because, although hermaphrodites, there are no internal connections between the worm’s male and female reproductive systems.