When I think of hibernation, my first thought is my high school English literature class on Washington Irving’s tale of a Dutch settler named Rip Van Winkle. The story’s setting is New York’s Catskills Mountains during the American Revolutionary period. In this tale, Rip Van Winkle was a fun-loving, lazy, henpecked husband who escaped his nagging wife by running to the mountains where he encountered strange men playing nine pins. After drinking their liquor, he fell asleep under a shady tree. Rip returned to his village after waking up only to find out that 20 years had passed and America was a already a new republic. Many of us would wish we can do just that when times are rough and wake up later when times are better.

Irving’s story of Rip Van Winkle was likely influenced by ancient folklores in Orkney (Scotland) where a drunken fiddler find trolls having a party, plays music with them for two hours and goes home to find that 50 years had passed. But there are even more older tales of a similar nature around the world, such as the German folktale of Peter Klaus, of Niamh and Oisin in Ireland, the ancient Jewish tale of Honi M’agel, the Chinese story of Ranka in 3rd century AD, the 8th century Japanese tale of Urashima Taro and the story of the Seven Sages by Diogenes Laertius of the 3rd century. The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus tells of Christians escaping Roman persecution by sleeping in a cave to awaken after a century to a new world wherein Christianity became the new religion of the Roman Empire.

As there are numerous variations of the hibernation theme in the literature, there are even more variations of hibernation in the natural world. Insects do it all the time; as do seeds of plants. Tiny invertebrates, like the tardigrade, remain in hibernation for over a hundred years in a dry state and ‘reawaken’ when exposed to water. As long as it is hibernating, the tardigrade can withstand extremes of pressure, temperature, desiccation and low oxygen. Artemia cysts, commonly known as brine shrimp eggs that hobbyists hatch to feed fish fry, behave like that too. They remain hibernating in a dry state and re-animate when placed in salt water, becoming the “sea monkeys” that most of us remember as a child. Other mammals do it too. Female kangaroos, bears and badgers can delay the implantation of the embryo by inducing reversible developmental arrest to postpone the period of birthing until months later when food is plentiful. Just like Rip Van Winkle, these animals escape inhospitable conditions by escaping in time.

Diapause (from the Greek dia meaning between and pauein meaning to stop), suspended animation, aestivation, hibernation and crytobiosis (hidden life) are terms that evoke images of a long, but temporary sleep. For most organisms that are unable to physically move away, it is their only means of surviving harsh environmental conditions until the next more favorable season. Even now, the science of suspended animation is advancing far beyond insects and arthropods. Non-injurious suspended animation can be induced in mice for a short time by replacing the oxygen in the air it breathes with hydrogen sulfide. The long term medical potential in human terms is delaying trauma from injury until more favorable medical interventions can be applied.

Where does fish come into this? First, let me tell you a story of my own fascination with one unusual class of tropical fish that do exactly the same. They are called annual killifish (from the Dutch word kill meaning small stream). They thrive only in seasonal pools that evaporate totally during the dry season. When the rains come the following year, or even five years later, the fish population returns again to re-populate the pond. They are not the lungfish that most of us might be familiar with. Lungfish ‘aestivate’ in mud chambers they create before the pond dries up. They continue breathing air through a hole on top of the moist chamber while at the same time reducing their metabolism. Annual fish are unique because they can completely stop at three specific diapause stages of their normal embryonic development. They escape in time by near zero metabolism and complete cessation of embryonic development. Though not as extremophile as the tardigrade, the diapause stages of the annual killifish are more resistant than non-diapause stages to extreme conditions in their environment

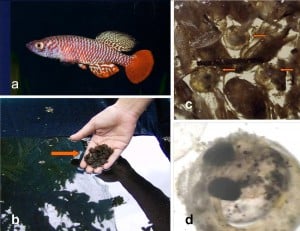

My first introduction to this fish was during the 1970’s in the laboratory of Jules Markofsky, who at the time was studying the annual killifish, Nothobranchius guentheri, for aging research at the Orentreich Foundation. Annual killifish live for about one year. Some species even have life spans as short as 4 months. Compare that to the guppy that can live as long as five years and the mouse or rat for about 4 years. Back then, so little is known about the biology of the killifish that we were unable to get enough embryos to hatch synchronously to do aging research. In fact, we sought help from the Long Island Killifish Association, an esoteric and dedicated group of hobbyists that maintain such rare fish in captivity. It was such a fascinating group that I, too, joined the Club.

Fish hobbyists know more about these unique and colorful killifish. And, there are dozens of such specialized clubs in US and Europe. In fact, one does not need to go to the jungle to find most of these species. Just meet with any one of the killifish hobbyists who can share some diapause eggs. Hobbyists continue to brave malarial mosquitoes and wild animals, even animals of the two-legged kind, to bring back live specimens from Africa and South America that are then bred in aquarium tanks. While environmental degradation and man-made land alterations likely have doomed scores of native populations, much of the species known today exist in the aquarium hobby.

After 25 years studying diapause in N. guentheri, combined with the work of other scientists/ hobbyists, I began to have a better idea of the environmental cues that trigger the onset and termination of diapause. The day-night cycle, temperature, humidity and maternal cues that influence the development of diapausing states in silkworm, for example, are the same in killifish—an unique example of convergent evolution.

How about malaria? Curiously, the geographic range of malarial mosquitoes and annual killifish in Africa and South America overlap. George Myers, a noted ichthyologist of his time, in the 1950’s first observed reduced incidence of mosquito bites in areas populated by killifish. Since then Richard Haas, Rudd Wildekamp, Jules Markofsky and I have proposed at various times in the last 30 years to use this fish for mosquito control. Since most countries have a few native species of annual killifish, we can even keep the environmentalists happy since we don’t need to introduce any exotic fish to do this. The local ones will do just as well. All we need is to grow and distribute a lot of them around.

The tribesmen in the sub-Sahara Africa already use annual killifish in freshwater storage containers and wells. Hobbyists already know that ‘killies’ are larvivorous. Yet, common anecdotal knowledge is not enough to push regulators and funding agencies to use this fish for mosquito control. Recently, the publication in the online journal Parasites & Vectors finally verified the anecdotal evidence by methodically demonstrating the feasibility of using killifish as mosquito control agents. In this paper, the embryos in the pre-hatching hibernating state were transported in moist peat moss and dropped in temporary ponds where they hatched, consuming all the mosquito larvae.

Although conventional larvivorous fishes have been used to rid mosquitoes in ponds as far back as the building of the Panama Canal, their use had been limited to more permanent waters. Fish predators, like Gambusia, work great on abandoned swimming pools after hurricanes, for example. But this fish has wrought havoc in many ecosystems because of their prolific and voracious nature. Transporting even native conventional live fish to remote areas is a big hassle. With only dirt roads and footpaths available to reach rain pools, mining pits and similar transient pools, transport by water trucks is just not practical.

Now we have a transportable fish in a bag. Instead of a water truck, a backpack is enough to carry a million diapausing killifish eggs! Sort of like Johnny Appleseed, another American legend, bringing bags of eggs instead of bags of apple seeds.

The idea of the ‘instant fish’ is nothing new. It’s been tried unsuccessfully a few times as a business. What’s new is taking this technology to a more useful purpose.

How can we transform this idea of “instant fish in a backpack” into something practical for malaria control in the future? Stay tuned to my next blog when I get re-animated again.

— Jonathan R. Matias

Suggested reading:

Annual fish biology

http://www.poseidonsciences.com/annualfish.html

mosquito control