This blog entry has its origins from a company newsletter I wrote in 2009 for scientists working on marine coatings.

Darlene Brezinski, the editor of Paint & Coatings Industry magazine, liked the topic so much and asked me to take excerpts from that newsletter into the article that appeared in the magazine on the same year. I share with you excerpts of that article here as a prologue to my next blog on HMS Beagle and Tara Oceans.

Why bother studying barnacles? Marine biofouling is such a multi-billion dollar problem because attachments on the bottom of the ship causes drag and increased fuel consumption. It is estimated that a supertanker from Saudi Arabia to Los Angeles port would cost an additional 1 million dollars worth of extra fuel if barnacles are present in the submerged portion of the hull. The barnacle, Balanus amphitrite, is the most ubiquitous fouling organism that tenaciously attach to the surface. It is perhaps one of the earliest invasive species since it is present in practically all major ports, around the world, having been a hitchhiker on ocean going vessels for over 3,000 years. To get them off the ship requires expensive dry docking, sand blasting. and re-painting. Prior to the 1990’s, all marine paints contained toxins to kill barnacle larvae before they settle on the bottom of the ship. That use has since been legislated out and the search is on for less toxic biocides and preferably nontoxic paint chemistries or repellents.

So, here is the excerpt from Poseidon Marine Science News and PCI magazine.

“Having been in fish biology in my earlier years and a biomedical scientist in my middle ones, my own passion for barnacle research did not come until later after meeting Dan Rittschoff at Duke University, Ron Price at the U.S. Naval Research Institute and Sister Avelin Mary at Sacred Heart Marine Research Centre (Tuticorin, India) in the early 1990’s. Barnacles are not exactly the cute furry creatures one can get so passionate about. I do have to admit that the interest was partially clouded by my capitalistic pursuits. Like many of us in this business, we write scientific articles about the biology of the barnacle, Balanus amphitrite amphitrite Darwin, and yet did not spare any second thoughts about why Darwin’s name came to be part of it. So, let me tell you why.

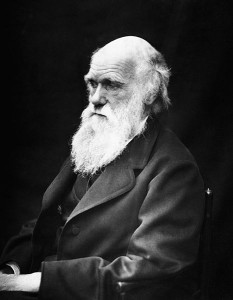

The Charles Darwin we are all familiar with is the English naturalist who wrote The Origins of Species and Natural Selection, which has since become the foundation for our understanding of evolution and the unifying explanation for the diversity of life on earth. He wrote about his theory in 1844, then quickly shelved it inside his desk drawer, specifically instructing his wife to release it for publication only if he died unexpectedly. Darwin was a modest man who shied away from controversies and he knew his theory will be so controversial, and even remains to be so on this 150th anniversary of writing the Origins.

For 20 years, the paper remained hidden until he received a letter from a young English naturalist, Alfred Russell Wallace, then living in an island of what is now Indonesia. In a malarial fit, Wallace remembered reading Thomas Malthus’ 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population (which coincidentally also inspired Darwin) and reached his own Eureka moment totally independently. He quickly dispatched a letter to Darwin describing an almost identical theory of evolution. In the typical Darwinian sense of fair play, he presented Wallace’s ideas and his own at the same time during the meeting of the prestigious Linnean Society, giving equal credit to the ideas of Wallace and the share of the controversy as well. Yet, Darwin is credited with the theory of natural selection because his ideas were written while Wallace was yet in his teens, over 20 years before.

Then, you may ask, what did he do for 20 years? Besides dealing with his failing health and the tragedies in his life, he was consumed by the passion of cataloguing barnacles. His interest in these tiny, ugly creatures began during his famous round the world voyage in HMS Beagle. Then, at the age of 26, young Darwin was exploring the Chilean coastline looking for biological specimens when he came upon a conch shell riddled with tiny boreholes despite its thick shell. Inside the hole was a microscopic creature, attached by its head to the shell and waving six tiny legs. Darwin was fascinated, knowing that it is a barnacle, but without a shell. It has never been described by any naturalist before. He was a disciplined taxonomist and organized the chaotic nomenclature of this organism, numbering over 1000 species, which were often misnamed during his time. Upon his return to England and immediately after writing his ideas on natural selection, at great expense to his health, he began his day and night obsession with barnacles that lasted for 8 years (1846-1854) cataloguing the collection from his voyage and from the hundreds more sent to him by mail from around the world .

What drove this passion about such a mundane organism? Perhaps a clue comes from the earlier anonymous publication of a controversial, incendiary, speculative book, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (later confirmed to be the work of Robert Chambers, a Scottish medical journalist). Widely panned and mocked for its evolutionary ideas even by Darwin’s friends, the failure of the book was a great personal disappointment because Darwin expected the same response to his own ideas in his theory lying inside his desk drawer. Even his best friend, the noted botanist Joseph Hooker wrote, “no one has the right to examine the origin of species who has not minutely described many.” Perhaps, one reason for this obsession was indeed to “minutely observe a distinct part of the natural world and in so doing earn his right to question their origins.”

Whatever the reason might be, Darwin started us all on a path of research towards understanding barnacle biology and the commercial opportunities that follow in its wake. As for me, at least I have someone else to blame now for my current obsession with barnacles — Charles Robert Darwin.”

–Jonathan R. Matias, Poseidon Sciences

Excerpted from: Poseidon Marine Sciences News, Subsea testing

Also, read the book Darwin and the Barnacle by Rebecca Stott. It is an engrossing story of Darwin’s passion for barnacles and the mystery of Darwin’s 20-year wait to publish his theory.