And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking

“Sea Fever” by John Masefield (English Poet Laureate, 1878-1967)

Standing at the base of a statue in Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan, my eyes wide open, gazing out to see far in the horizon, I remember the long wait under the blazing July sun for the most fascinating parade I have ever yet to see. Not a parade of men and machines. It was a parade of the Tall Ships, fully rigged sailing vessels – schooners, brigantines, brigs and barques. All 16 of the 25 remaining tall ships around the world, led by the USCGC Eagle, came to view, sailing past the Verrazano Narrows Bridge into NY Harbor, along with hundreds of other sail boats and ships of all sizes and shapes. That was the 4th of July, 1976, the Bicentennial of the American Declaration of Independence and Operation Sail. For a young immigrant like me and the rest of the 5 million watching along the Hudson River on that day, the parade was truly awe inspiring. Even the Soviets, at the height of the Cold War, had their tall ships, Tovarishch and Kruzenshtern , joined America for this display. For the Soviet cadets on the tall ships, this parade was their first contact with the United States and their first real understanding that “Americans were not devils…” On that day, New York City’s struggles–race riots, economic woes—just simply faded away.

That parade got me hooked on sailing vessels, small and big, forever.

The Morgan

Every time I look at a sailing ship, my mind drifts to the images of that day in 1976. The reason these memories came back again weeks ago was a NY Times article on the Charles W. Morgan, the last surviving wooden whaling vessel that once numbered over 2,700. A small army of marine scientists, engineers, historians, graphic artists and shipwrights, aided by the latest in modern technology, are helping forensic specialists to decipher the way the ship was originally built back in 1841 in New Bedford, Massachusetts. New Bedford was once the bustling seaport for whaling ships that supplied the world with whale oil for lamps, with baleen (the tough part of the mouth) for buggy whips and corset stays. Later, when petroleum became the cheaper alternative to whale oil and when horse drawn carriages were made obsolete by automobiles (and no need for buggy whips), the Morgan came to rest in Mystic, Connecticut as a museum piece. That was where I saw the Morgan a long long time ago, docked along the wharf. Not a soul was interested enough to board her except me on that summer afternoon.

The Morgan was not majestic like the tall ships It was hulking, somber–looking and utilitarian. It is an example of a bygone era popularized by the 1851 novel, Moby Dick, the story of Captain Ahab’s obsession to hunt the great white whale. The future author, Hermann Melville, came on board as a whaler on a similar ship that same year the Morgan was built. The novel was authentic in every detail, down to the processing of the whale meat since Melville lived through it while 18 months at sea. Though a fantasy, the novel had some basis of truth. Captain Ahab’s death was mostly how whalers died during the hunt and the ship being sunk by a whale did happen on an actual whaling ship, the Essex, rammed and sunk by a sperm whale. Whaling back then is like drilling for oil in the open sea, just infinitely more dangerous, without the comforts and the safety we know today. You can feel the danger by simply reading the cenotaphs (Greek meaning empty grave) inside the Seamen’s Bethel, the non-denominational church for the whalers of New Bedford. The cenotaph was a tablet placed on the side walls of the church as a memorial by the families since there were no bodies to bury when the whalers died of accidents, drowning, sharks and diseases far away from home.

For those who have no feeling for a ship, the walk on its deck is just like walking on any other decrepit ship waiting mercifully for the barnacles and shipworms to eat through the hull. For me, as an amateur historian, it was a walk through history, not of great sea battles or great discoveries, but a walk through the history of simple, tough and courageous men of the sea. Long before American naval power dominated the oceans, it was men on ships like the Morgan that projected the growing American economic power of the 19th century.

What I see beyond the restoration of the Morgan is the ever increasing awareness and appreciation of maritime history not just in the United States, but also around the world. Discoveries of near perfectly preserved trading vessels in the depths of the Black Sea, reconstructions of Greek and Roman warships built two millennia ago, the 400 year old Virginia (a sailing vessel used by American colonists), Scandinavian long boats used by the Vikings and many more. In Italy, the Lake Nemi ships built by the Roman Emperor Caligula had bilge pumps similar in operation to our modern ones, piston pumps that pipe in hot and cold water throughout the ship (only re-invented again in the Middle Ages), ball bearings to turn statues (Thought to be first conceived by Leonardo da Vinci during the Renaissance and patented by Sven Gustaf Wingqvist in 1907)) and iron anchors that only came to use again a thousand years later. What we thought of as modern inventions turns out to have more ancient beginnings.

Admiral Zheng He

During the Ming dynasty from 1405 to 1433, the 300+ ships of the Chinese Admiral Zheng He comprised 7 expeditions, that took this huge armada all the way to India, Africa and Saudi Arabia. Extensive written accounts of the voyages tell of 5-masted ships, 200 to 400 feet long, carrying 28,000 men, traversing the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean reaching as far away as Madagascar in Africa and up the Red Sea to Jedda. The expeditions sought a rival emperor who fled (considered the longest maritime manhunt in history), suppress pirates in the South China Sea,

explore new worlds, establish trading colonies and project the power of the Chinese Empire. The Admiral fought a land war against the Kingdom of Kotte in Ceylon and brought back emissaries from 30 states to pay respect to the Emperor. As a Muslim from Yunnan Province, Zheng He also expanded the range of Chinese Muslim influence in Asia, with contemporary scholars crediting Zheng He with the Islamic beginnings in Indonesia and Malaya. Life-size replicas of such magnificent ships are yet to made and we can only wonder how such ancient leviathans managed to make this trek multiple times.

Borobudur, Phoenicia and Philip Beale

While many working replicas of ancient ships continue to be made and sailed, perhaps the more recent expeditions on the Borobudur and Phoenicia by Philip Beale’s team are great examples of the passion for high seas adventure.

Borobudur Temple is considered the world’s largest Hindu stupa (Sanskrit meaning “heap”), a mound-like structure considered holy because of the presence of Buddhist relics. Located in the island of Java in Indonesia, Borobudur was built during the 8th century and considered the inspiration for similar structures found in Cambodia’s Anchor Wat centuries later. The intricate artwork within this vast spiritual complex includes over 1460 reliefs on its wall, 11 of which described the maritime events of the time. Of these 11, five are reliefs of a previously unknown ship design, later called the Borobudur ships. The saga describes Indonesian seafarers on ships laden with spices venturing far out beyond the archipelago to the Indian Ocean and to Africa centuries before Borobudur was built. Pliny, the Roman historian of the 1st century AD, described seafarers from the East coming to Africa on ships and modern historians agree that Indonesians did venture as far as Africa to establish trading colonies.

Borobudur Temple is considered the world’s largest Hindu stupa (Sanskrit meaning “heap”), a mound-like structure considered holy because of the presence of Buddhist relics. Located in the island of Java in Indonesia, Borobudur was built during the 8th century and considered the inspiration for similar structures found in Cambodia’s Anchor Wat centuries later. The intricate artwork within this vast spiritual complex includes over 1460 reliefs on its wall, 11 of which described the maritime events of the time. Of these 11, five are reliefs of a previously unknown ship design, later called the Borobudur ships. The saga describes Indonesian seafarers on ships laden with spices venturing far out beyond the archipelago to the Indian Ocean and to Africa centuries before Borobudur was built. Pliny, the Roman historian of the 1st century AD, described seafarers from the East coming to Africa on ships and modern historians agree that Indonesians did venture as far as Africa to establish trading colonies.

Philip Beale, an Englishman who became captivated with this story, joined the ranks of inspired modern mariners who took it upon themselves to build the exact replica of the ship. The ship, fitted with outriggers as shown in the carving, was built the same way ships were constructed during the period, with Indonesian hardwood and wooden pegs instead of nails. When finally built, the ship captain, Alan Campbell, recalls,

“Some ships, when you first see them, you’re not sure which end is the front and which is the back. When I first saw a picture of this ship, I wasn’t sure which end was the top.” Yet when she cuts through the water, the Borobudur possesses an undeniable majesty. “

His Borobudur Ship Expeditions had taken the exact replica of the ship through the Indian Ocean and to Africa in 2004, proving that ancient Indonesian mariners could have accomplished this feat with the Borobudur ships in the past.

Beale’s passion did not end with Borobudur. The next obsession was to build a Phoenician ship to validate the ancient story of Phoenicians circumnavigating Africa 3,000 years ago. Phoenicia (also referred to in Latin as Punic) comprises city states along the coasts of the Mediterranean, from North Africa and extending to Syria today. Its power rested on commerce due to its vast fleet that roamed the Mediterranean basin at will. Because of its naval might and trading power, Phoenician alphabet was adopted by the early Greeks, then by the Etruscans, the Romans and eventually to become part of our modern alphabet. Herodotus, the Greek historian, wrote the story of King Necho II of Egypt who commissioned the Phoenicians in 600 BC to circumnavigate Africa, previously considered an impossible task. Like all mariners, Phoenician mariners rose to the challenge, built the ship in Egypt, sailed it through the Red Sea and eventually returned via the Mediterranean three years later.

Beale’s passion did not end with Borobudur. The next obsession was to build a Phoenician ship to validate the ancient story of Phoenicians circumnavigating Africa 3,000 years ago. Phoenicia (also referred to in Latin as Punic) comprises city states along the coasts of the Mediterranean, from North Africa and extending to Syria today. Its power rested on commerce due to its vast fleet that roamed the Mediterranean basin at will. Because of its naval might and trading power, Phoenician alphabet was adopted by the early Greeks, then by the Etruscans, the Romans and eventually to become part of our modern alphabet. Herodotus, the Greek historian, wrote the story of King Necho II of Egypt who commissioned the Phoenicians in 600 BC to circumnavigate Africa, previously considered an impossible task. Like all mariners, Phoenician mariners rose to the challenge, built the ship in Egypt, sailed it through the Red Sea and eventually returned via the Mediterranean three years later.

Could the Phoenicians have really accomplished it? Since written records were made in papyrus that disintegrated with age, the only way to settle this question is to build a Phoenician ship and sail it around Africa. After assembling his team of ship builders and marine archaeologists in Syria, Philip Beale built a replica based on archaeological artifacts, shipwrecks and descriptions available in the historical records. Last October, the ship, Phoenicia, circumnavigated Africa, returning to dry dock in Syria last October, 2010, finally proving that it can certainly be one.

On the Galleon Trade

This is a great year for ship reconstructions and expeditions. The replica of the galleon, Andalucia, was made to highlight the celebration of the Galleon Trade between Manila and Acapulco, a period of over 200 years when goods from Asia came to the New World, not via the more famous Silk Route, but by ships built in the then Spanish colony called the Philippines. The replica of the Andalucia, though not the life size working model, was thought to be the first ship that traversed the entire world. Besides bringing the riches of Asia and plundered wealth of the colonies to the West, the Galleon Trade brought Western goods and historical connections between people over those two centuries. Even now Mexican coastal families carry the last names of native Filipino seafarers that likely had jumped shipped (perhaps, becoming the first Asian illegal aliens in Mexico). There are coastal communities in Mexico where the favorite alcoholic drink is called tuba, derived from fermented sap of coconuts, popular only in the Philippines. Likewise, Filipinos came to like the Mexican champurado (chocolate rice porridge) and tamales.

On my first visit to the island of Panay in the Philippines in 1994, I was struck by how denuded the mountains were and was told that the island only had less than 5% remaining of its virgin forest cover. My first thought was that more recent uncontrolled harvesting of wood for timber and firewood were the root causes of the deforestation. Only after talking with a local historian that I came to know the center of shipbuilding was in the old city of Iloilo in Panay because of its natural harbor and thick forests. The Spanish colonial government had consumed all the big hardwood trees 200 years earlier to build the ships that served the Galleon Trade.

My obsession with the balanghai

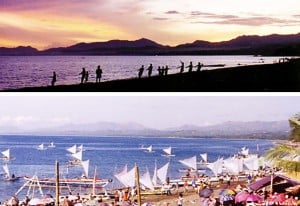

Having lived and worked in New York City all my adult life, I often dreamed of living in a tropical island, a house by the sea, with coconut palms and beautiful sunsets. My wife and I visited many islands in SE Asia and did chose the island of Panay and the town of Miag-ao, where I continued research on totally new directions—barnacles, spiny lobsters, endangered clams, eels and tropical abalone. What captivated me on my first visit to Miag-ao was the view of the small fishing boats going out to sea at night with lanterns and the hundred or so boats racing to market in the early morning to sell the night’s harvest of fish. It’s the delight of seeing the same boats on a different season, slowly moving parallel to the beach, with kerosene lamps lit up, catching squid; of local tales of a shark that once roamed the bay, keeping the fishermen from venturing out to sea, of wild tales of mysticisms and night creatures of ancient legends. There were many reasons to be there, but it was the sight of fishing boats that kept me often by the sea .

During the five year sojourn in Miag-ao, I also learned about the local customs, the local stories, the issues of being foreign having lived in another island in my youth, speaking a different language altogether. I also learned about Maragtas, a tale written by a local islander, Pedro Alcantara Monteclaro, a revolutionary figure during the Philippine Revolution against Spain. Maragtas tells the story of the Ten Datus of Borneo, escaping a harsh ruler on their long boats with their families, searching for a new home in distant lands. It tells of them landing in the island of Aninipay (now Panay) within the shadow of the mystical Mt. Madia-as, the negotiations with the local Negrito tribesmen for the datus to occupy the lowlands and the Negritos the highlands. It was a tale of maritime adventure, of love stories and of many things. But, I was most captivated by the vision of the boat called the barangay or balangay that the datus used for their escape.

The word barangay refers not only to the boat, but also the village. Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian scholar who accompanied Magellan in his voyage to circumnavigate the world, called these boats by the Europeanized version of balanghai. Pigafetta was one of the 18 survivors that returned to Spain on the ship Victoria out of the original 241 that constituted Magellan’s 5-ship flotilla. The biggest balanghai, measuring 25 meters, can carry the entire village. They are also war canoes used to raid neighboring islands. Much of that maritime history was lost when the Spanish Conquistadors came, after Ferdinand Magellan landed in 1521 (and killed in battle with a local datu, Lapu-lapu) in the nearby island of Mactan.

The later conquest of the islands was made possible not by Spanish warships. They were too big, too slow and the draft too deep to navigate close to the coast to make effective use of their cannons. The ships of the Conquistadors were mostly anchored in the natural harbors of Cebu or Iloilo from where they boarded hundreds of balanghais, referred by the Spanish as caracoa, manned mostly by native allies to attack the next island. After consolidating their conquest, the colonial government banned the building of balanghai, preventing interisland communication and trade except through permission of the colonial government. The control was so total that even the first letters of the adopted Spanish last names were given according to the island of birth, thus enabling the government to track origins of people. The natives were then redirected instead to build churches, forts and serve in the mines and plantations. Boat building skills were lost, except in the unconquered territories of the southern islands where the same boat building tradition continues to this day in remote islands.

In pre-colonial times, the city of Butuan in the island of Mindanao was the center of commerce, with ships coming from the Sri-Vijayan Empire of Java and from China and India. In the late 1970’s, nine balanghais were found purely by accident, buried and preserved for centuries in the mud , the largest estimated at 25 meters. While 6 boats remained buried in their original waterlogged condition, radiocarbon dating placed one of the three excavated balanghai to year 320, the second in 990 and the third in 1250. These are the oldest, pre-colonial wooden boats found in SE Asia thus far.

On December 13, 2010 the replica of a balanghai, built by Arturo Valdez and his team of former Everest mountaineers , completed its 14,000 km odyssey, through the South China Sea, taking this boat to Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore, finally berthing on its home base in Manila. Like the Phoenicia and Borobudur expeditions, the journey of the balanghai also proved the ancient accounts that such boats had roamed throughout the archipelagic countries of South East Asia and perhaps beyond.

The balanghai is especially interesting to me because I had the same passion that began in 1997, yet was never fulfilled. I visited the National Museum to see one of the balanghais on display and discussed with Rey Santiago, the senior archaeologist, on the possibility of building such a working replica in the future. What developed in 1998 was a concept to build such an exact replica to sail around South East Asia in the same way that Art Valdez was able to successfully accomplish a decade later. Finding the enormous hardwood tress needed for the planks and the carvers with the abilities to build one were daunting tasks. And, new challenges of the times distracted me from chasing that dream.

A Nova Pacific newsletter I wrote in 1998 while I was in Miag-ao discussed the balanghai in more detail and thought the excerpt below from that publication might be illuminating:

Folktales handed down from generations tell of entire communities migrating from distant lands to settle in our islands aboard a legendary ship called the balanghai. And, upon landing in their new found land, the voyagers continued to carry on the traditions of their homeland. The legendary adventure of the ten Bornean datus, led by Datu Puti, and their settlement of Aninipay (now called Panay Island) in the Visayas spoke well of our ancient maritime heritage.. The advent of the Spanish era in the 16th century destroyed much of our seafaring legacy and, with its loss, much of our cultural identity as a people.

What is a Balanghai?

The term balanghai came originally from the Italian spelling of Antonio Pigafetta’s 16th century writings about the barangay. What we really knew about the balanghai came from Francisco Ignacio Alcina’s 1668 manuscript which described life in the archipelago for the Spanish King. He described the balanghai as a 15 meter long plank built wooden boat propelled through the sea with a square sail on a tripod mast. Its rowers, numbering 10 to 20 men, sit on platforms along the outriggers (2 to 3 rows on each side). These ancient mariners paddled from “sunrise to sunset” at high speeds in unison to the songs and chants about heroes and their deeds. Aboard the balanghai, the most important person was not the datu but the crier or singer whose songs, not drums like in Chinese or Japanese boats, set the rhythm of the rowers. When traveling before the wind, the balanghai was said to go at a speed of 12 to 15 knots compared to the galleon’s 5 to 6.

The balanghai is not just a ship for long voyages. It is also a warship, highly maneuverable, versatile vessel best

suited to the shallow waters of the archipelago. Other than ancient writings and folk tales, there was no real proof of the balanghai’s existence until 1976, when by sheer luck, a Butuan City Engineer named Proceso S. Gonzales, unearthed planks of an ancient boat buried in the mud. The National Museum dispatched archaeologists to the site and discovered a national treasure of several balanghais, which when carbon dated ranged in age from the 4th to the 13th centuries.

These ancient boats, whose construction remained unknown for over a thousand years, lay buried under the mud in Butuan City. What the archaeologists had unearthed corroborated much of Alcina’s detailed descriptions of the balanghai. Having been a master shipwright himself before coming to the Philippines and have built such vessels during his travel through the Visayan islands, Alcina’s writings of the balanghai had the details only an expert could have provided. The construction is unlike our more modern technique of boat-building where the keel and the ribs are laid first and from which the planks are fastened with nails or spikes. The construction of the balanghai involved building the planks first and then fastening the ‘ribs’ after the ship has taken shape. This same technique was employed in the building of Viking ships. Each plank is carved expertly from a tree with an ax and fitted edge to edge perfectly with wooden pegs–a no mean feat for a boat the size of a balanghai. Caulking was made up of fibers and resins. Alcina’s description of the balanghai was indeed proven true by the archaeological findings in Butuan.

What makes the balanghai so important?

The balanghai, with its various names, the biniday or barangay, is not just an ancient ship. It is the term from which our basic sociopolitical unit was derived. Before the Spanish era, it refers to a community or settlement led by a monarchical chieftain, the datu, chosen for his wisdom and valor. The renaming of this political unit into a barrio during the American occupation has symbolically subverted the Filipino psyche from an independent society into that of a conquered one. In 1974, pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 557, the term barangay used to describe our community was again adapted as a reaffirmation of our national identity.

Just like the Viking ships of Scandinavia, our balanghai is a symbol of the maritime heritage of our civilization that links us with our Southeast Asian neighbors. It can be a common link between the islands and its diverse cultures; a means of creating a national unity.

For centuries, our balanghai had been a myth. To most Filipinos, the balanghai remains a mere symbol and few understand its true value. To transform the myth and the symbol into a recognizable truth one must therefore bring the symbol into reality. To draw the balanghai from the abstract into the realm of the senses, one must bring the true balanghai to life.

From: JR Matias, Nova Pacific newsletter, 1998

The oceans as the ultimate freeway

Seafaring legacies are aplenty. Visit any nation that has a coastline, talk to any of the older villagers living by the sea and you’ll see what I mean. Seafarers are among the most vibrant and adventurous people I know. When they leave the comforting sight of land, dangers lurk in every wave, every change in the weather. That has always been so for millennia and have not changed much even with our modern technology. For mariners, beyond the national territorial limits, the ocean is like an autobahn, a freeway without lanes and without borders. Unlike the Silk Route, where a traveler needs permission to pass through kingdoms and fiefdoms, the ocean was free, unfettered access. And for thousands of years, it was the communication highway, the ocean the equivalent of our modern Internet.

Traditions

The maritime tradition of the Philippine Islands continues today, though most of this tradition now lay in more distant oceans under many different flags. There are about 100 maritime academies in the islands, sending 230,000 seamen to man the world’s tankers, bulk carriers and cruise ships. Of the 1 million seamen worldwide, 25% of them are Philippine seafarers. So, it is not so surprising that every time a ship is hijacked off the Somali coast, invariably there would be a number of Filipino crewmembers taken hostage, more than any nationality. There was a time in 2008 when one Filipino seaman was captured on foreign ships every 6 hours.

Why so many Filipino seamen? It can’t simply be explained by economic terms when there are so many more island nations with similar economies, yet with little participation in the maritime industry. Perhaps, the Philippine psyche is still tied with the sea despite the 400-year ban that Spain imposed on its former conquered territories. The thousands of years of riding the balanghai cannot be erased by such a brief interlude; it was just simply lying dormant, biding time to re-express once again.

Or, perhaps it is simply in the blood !

Jonathan R. Matias

Chief Science Officer

Poseidon Sciences Group

New York, NY USA

Additional reading:

http://www.balangay-voyage.com/index.php

http://agiledeals.com/2009/05/butuan-and-balanghai-a-journey-through-time/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nemi_ships

http://maritimeasia.ws/topic/shiptypes.html

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,480337,00.html

http://www.borobudurshipexpedition.com/design-outline.htm

http://www.phoenicia.org.uk/discovering-theship.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zheng_He

About the whaling ship, the Morgan

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/17/science/17ship.html

On Frank Braynard, founder of OPSail and maritime historian

http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20071217/news_1m17braynard.html