A new study suggests that people are more likely to misidentify a toy as a weapon after seeing a Black face than a White face, even when the face in question is that of a five-year-old child.

The research is published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

“Our findings suggest that, although young children are typically viewed as harmless and innocent, seeing faces of five-year-old Black boys appears to trigger thoughts of guns and violence,” said lead study author Andrew Todd, an assistant professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at the University of Iowa.

The inspiration for the series of studies, conducted by Todd and University of Iowa colleagues, Kelsey Thiem and Rebecca Neel, began with a real-life observation:

“In this case, it was the alarming rate at which young African Americans — particularly young Black males — are shot and killed by police in the U.S.,” explains Todd. “Although such incidents have multiple causes, one potential contributor is that young Black males are stereotypically associated with violence and criminality.”

Previous research has shown that people are quicker at categorizing threatening stimuli after seeing Black faces than after seeing White faces, which can result in the misidentification of harmless objects as weapons. Todd and colleagues wanted to find out whether the negative implicit associations often observed in relation to Black men would also extend to Black children.

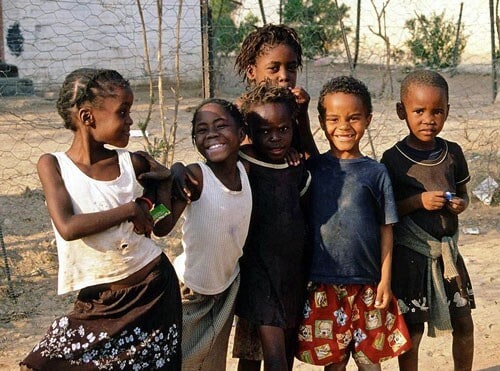

The researchers presented 64 White college students with two images that flashed on a monitor in quick succession. The students saw the first image — a photograph of a child’s face — which they were told to ignore because it purportedly just signaled that the second image was about to appear. When the second image popped up, participants were supposed to indicate whether it showed a gun or a toy, such as a rattle. The photographs of children’s faces included six images of Black five-year-old boys and six images of White five-year-old boys.

The data revealed that the student participants tended to be quicker at categorizing guns after seeing a Black child’s face than after seeing a White child’s face. Participants also mistakenly categorized toys as weapons more often after seeing images of Black boys than after seeing images of White boys.

However, they mistakenly categorized guns as toys more often after seeing a White child’s face than after seeing a Black child’s face.

The researchers’ analyses showed that the negative bias linking Black faces with threatening objects was driven entirely by automatic associations, which can unintentionally influence behavior.

In a second set of experiments, 131 White college students were shown faces of both children and adults before categorizing the second image as either a tool or a gun.

Again, Todd and colleagues found that seeing a Black face, regardless of whether it belonged to an adult or a child, elicited a bias whereby the participants categorized objects as weapons. Participants classified guns more quickly after seeing a Black face than after seeing a White face, and were more likely to mistakenly classify the non-threatening objects as guns after seeing a Black face.

A final experiment revealed that even threat-related words — including “violent,” “dangerous,” “hostile,” and “aggressive,” — were more strongly associated with images of young Black boys than with images of young White boys.

“One of the most pernicious stereotypes of Black Americans, particularly Black men, is that they are hostile and violent,” Todd and colleagues write. “So pervasive are these threat-related associations that they can shape even low-level aspects of social cognition.”

The researchers were surprised to find that images of harmless-looking five-year-olds could elicit threat-related associations that were on par with those elicited by images of adults. Todd and his colleagues hope to conduct further research into the extent of this implicit bias, investigating, for example, whether it also applies to Black women and girls.

Actually the negative bias was seen in white subjects. We cannot make a conclusion for other races or cultures based on this study.