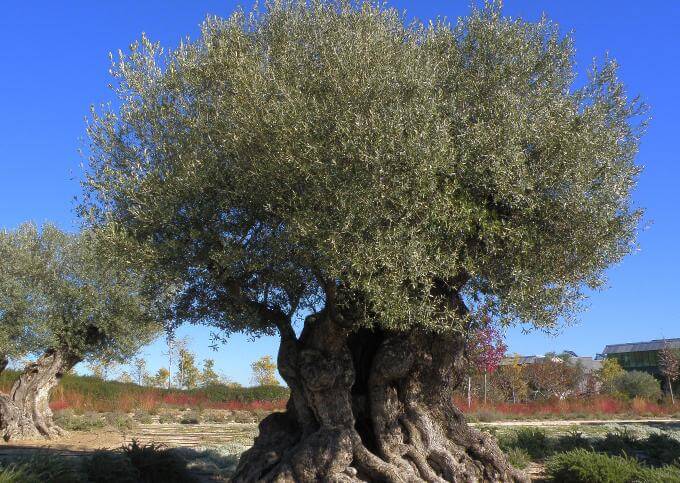

The olive was one of the first trees to be domesticated in the history of mankind, probably some 6,000 years ago. A Mediterranean emblem par excellence, it is of vital importance to the Spanish and other regional economies (Italy, Greece and Portugal). In fact, Spain is the leading producer of olive oil in the world. Every year, nearly three million tons of oil are produced, for local consumption and export. Spain produces one third of this total.

Nonetheless, up to now, the genome of the olive tree were unknown. The genome regulate such factors as the differences among varieties, sizes and flavor of the olives, why the trees live so long or the reasons for their adaptation to dryland farming.

Now a team of researchers from the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona, the Real Jardin Botánico (CSIC-RJB) and the Centro Nacional de Análisis Genómico (CNAG-CRG), has brought new insight to the genetic puzzle of the olive tree, by sequencing the complete genome of this species for the first time ever. The results of this work, fully funded by Banco Santander, have been published this week in the groundbreaking Open Access and Open Data journal GigaScience. The article will pave the way to new research work that will help olive trees in their development and protecting them from infections now causing major damage, such as the attacks of bacteria (Xilella fastidiosa) and fungi (Verticillium dhailae).

“Without a doubt, it is an emblematic tree, and it is very difficult to improve plant breeding, as you have to wait at least 12 years to see what morphological characteristics it will have, and whether it is advisable to cross-breed,” says principal author of this paper Toni Gabaldón, ICREA research professor and head of the comparative genomics laboratory at the CRG. “Knowing the genetic information of the olive tree will let us contribute to the improvement of oil and olive production, of major relevance to the Spanish economy,” he adds.

Private funding to support public science

The story of this project begins with a presentation, a coincidence and a challenge. Four years ago, Gabaldón worked with Pablo Vargas, a CSIC researcher at the Real Jardín Botánico, on the presentation of scientific results of projects focused on endangered species, such as the Iberian lynx, that had been financed by Banco Santander.

At that time, Banco Santander had expressed great interest in financing scientific projects in Spain. Over the course of the presentation, Pablo Vargas proposed to Emilio Botín the complete sequencing of the olive tree genome, using the same technology as had been used to sequence the lynx; in other words, the most state-of-the-art technological strategy to achieve a high-quality genome.

Five months after that meeting, a contract was signed to carry out the first complete sequencing of the olive tree’s DNA, a three-year research effort coordinated by Pablo Vargas.

“There are three phases to genome sequencing: first, isolate all of the genes, which we published two years ago. Second, assemble the genome, which is a matter of ordering those genes one after the other, like linking up loose phrases in a book. Last, identify all of the genes, or binding the book. The latter two phases are what we have done and are now presenting,” says the CSIC Real Jardín Botánico researcher.

To continue with the book analogy, according to Tyler Alioto of the CNAG-CRG “this genome has generated some 1.31 billion letters, and over 1,000 GBytes of data. We are surprised because we have detected over 56,000 genes, significantly more than those detected in sequenced genomes of related plants, and twice that of the human genome.”

Decoding its evolutionary history

In addition to the complete sequencing of the olive tree genome, researchers have also compared the DNA of this thousand-year-old tree with other varieties such as the wild olive. They have also found the transcriptome, the genes expressed to determine what differences exist on the genetic expression level in leaves, roots and fruits at different stages of ripening.

The next step, researchers say, will be to decode the evolutionary history of this tree, which has formed part of old-world civilizations since the Bronze Age. At that time, in the eastern Mediterranean, the process of domesticating wild olive trees that led to today’s trees began. Later, selection processes in different Mediterranean countries gave rise to the nearly 1,000 varieties of trees we have today.

Knowing the evolution of olive trees from different countries will make it possible to know their origins and discover the keys that have allowed it to adapt to very diverse environmental conditions. It will also help discover the reasons behind its extraordinary longevity, as the trees can live for 3,000 to 4,000 years.

“That longevity makes the olive tree we have sequenced practically a living monument,” says Gabaldón. “Up to now, all of the individuals sequenced, from the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) to the first human being analyzed, have lived for a certain time, depending on their life expectancy, but then died or will die. This is the first time that the DNA of an individual over 1,000 years old, and that will probably live another 1,000 years, has been sequenced.” say Gabaldón and Vargas.