Scientists at the Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, have created the first ever hologram of a single light particle. The spectacular experiment, reported in the prestigious journal Nature Photonics, was conducted by Dr. Radoslaw Chrapkiewicz and Michal Jachura under the supervision of Dr. Wojciech Wasilewski and Prof. Konrad Banaszek. Their successful registering of the hologram of a single photon heralds a new era in holography: quantum holography, which promises to offer a whole new perspective on quantum phenomena.

“We performed a relatively simple experiment to measure and view something incredibly difficult to observe: the shape of wavefronts of a single photon,” says Dr. Chrapkiewicz.

In standard photography, individual points of an image register light intensity only. In classical holography, the interference phenomenon also registers the phase of the light waves (it is the phase which carries information about the depth of the image). When a hologram is created, a well-described, undisturbed light wave (reference wave) is superimposed with another wave of the same wavelength but reflected from a three-dimensional object (the peaks and troughs of the two waves are shifted to varying degrees at different points of the image). This results in interference and the phase differences between the two waves create a complex pattern of lines. Such a hologram is then illuminated with a beam of reference light to recreate the spatial structure of wavefronts of the light reflected from the object, and as such its 3D shape.

One might think that a similar mechanism would be observed when the number of photons creating the two waves were reduced to a minimum, that is to a single reference photon and a single photon reflected by the object. And yet you’d be wrong! The phase of individual photons continues to fluctuate, which makes classical interference with other photons impossible. Since the Warsaw physicists were facing a seemingly impossible task, they attempted to tackle the issue differently: rather than using classical interference of electromagnetic waves, they tried to register quantum interference in which the wave functions of photons interact.

Wave function is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics and the core of its most important equation: the Schrödinger equation. In the hands of a skilled physicist, the function could be compared to putty in the hands of a sculptor: when expertly shaped, it can be used to ‘mould’ a model of a quantum particle system. Physicists are always trying to learn about the wave function of a particle in a given system, since the square of its modulus represents the distribution of the probability of finding the particle in a particular state, which is highly useful.

Wave function is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics and the core of its most important equation: the Schrödinger equation. In the hands of a skilled physicist, the function could be compared to putty in the hands of a sculptor: when expertly shaped, it can be used to ‘mould’ a model of a quantum particle system. Physicists are always trying to learn about the wave function of a particle in a given system, since the square of its modulus represents the distribution of the probability of finding the particle in a particular state, which is highly useful.

“All this may sound rather complicated, but in practice our experiment is simple at its core: instead of looking at changing light intensity, we look at the changing probability of registering pairs of photons after the quantum interference,” explains doctoral student Jachura.

Why pairs of photons? A year ago, Chrapkiewicz and Jachura used an innovative camera built at the University of Warsaw to film the behaviour of pairs of distinguishable and non-distinguishable photons entering a beam splitter. When the photons are distinguishable, their behaviour at the beam splitter is random: one or both photons can be transmitted or reflected. Non-distinguishable photons exhibit quantum interference, which alters their behaviour: they join into pairs and are always transmitted or reflected together. This is known as two-photon interference or the Hong-Ou-Mandel effect.

“Following this experiment, we were inspired to ask whether two-photon quantum interference could be used similarly to classical interference in holography in order to use known-state photons to gain further information about unknown-state photons. Our analysis led us to a surprising conclusion: it turned out that when two photons exhibit quantum interference, the course of this interference depends on the shape of their wavefronts,” says Dr. Chrapkiewicz.

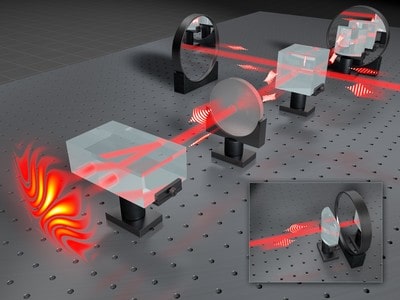

Quantum interference can be observed by registering pairs of photons. The experiment needs to be repeated several times, always with two photons with identical properties. To meet these conditions, each experiment started with a pair of photons with flat wavefronts and perpendicular polarisations; this means that the electrical field of each photon vibrated in a single plane only, and these planes were perpendicular for the two photons. The different polarisation made it possible to separate the photons in a crystal and make one of them ‘unknown’ by curving their wavefronts using a cylindrical lens. Once the photons were reflected by mirrors, they were directed towards the beam splitter (a calcite crystal). The splitter didn’t change the direction of vertically-polarised photons, but it did diverge diplace horizontally-polarised photons. In order to make each direction equally probable and to make sure the crystal acted as a beam splitter, the planes of photon polarisation were bent by 45 degrees before the photons entered the splitter. The photons were registered using the state-of-the-art camera designed for the previous experiments. By repeating the measurements several times, the researchers obtained an interference image corresponding to the hologram of the unknown photon viewed from a single point in space. The image was used to fully reconstruct the amplitude and phase of the wave function of the unknown photon.

The experiment conducted by the Warsaw physicists is a major step towards improving our understanding of the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. Until now, there has not been a simple experimental method of gaining information about the phase of a photon’s wave function. Although quantum mechanics has many applications, and it has been verified many times with a great degree of accuracy over the last century, we are still unable to explain what wave functions actually are: are they simply a handy mathematical tool, or are they something real?

“Our experiment is one of the first allowing us to directly observe one of the fundamental parameters of photon’s wave function – its phase – bringing us a step closer to understanding what the wave function really is,” explains Jachura.

“Our experiment is one of the first allowing us to directly observe one of the fundamental parameters of photon’s wave function – its phase – bringing us a step closer to understanding what the wave function really is,” explains Jachura.

The Warsaw physicists used quantum holography to reconstruct wave function of an individual photon. Researchers hope that in the future they will be able to use a similar method to recreate wave functions of more complex quantum objects, such as certain atoms. Will quantum holography find applications beyond the lab to a similar extent as classical holography, which is routinely used in security (holograms are difficult to counterfeit), entertainment, transport (in scanners measuring the dimensions of cargo), microscopic imaging and optical data storing and processing technologies?

“It’s difficult to answer this question today. All of us – I mean physicists – must first get our heads around this new tool. It’s likely that real applications of quantum holography won’t appear for a few decades yet, but if there’s one thing we can be sure of it’s that they will be surprising,” summarises Prof. Banaszek.

Physics and Astronomy first appeared at the University of Warsaw in 1816, under the then Faculty of Philosophy. In 1825 the Astronomical Observatory was established. Currently, the Faculty of Physics’ Institutes include Experimental Physics, Theoretical Physics, Geophysics, Department of Mathematical Methods and an Astronomical Observatory. Research covers almost all areas of modern physics, on scales from the quantum to the cosmological. The Faculty’s research and teaching staff includes ca. 200 university teachers, of which 88 are employees with the title of professor. The Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, is attended by ca. 1000 students and more than 170 doctoral students.

SCIENTIFIC PAPERS:

“Hologram of a Single Photon”; R. Chrapkiewicz, M. Jachura, K. Banaszek, W. Wasilewski; DOI: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.129