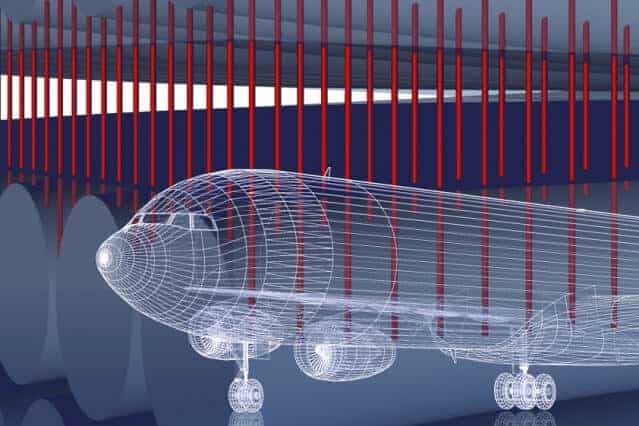

The newest Airbus and Boeing passenger jets flying today are made primarily from advanced composite materials such as carbon fiber reinforced plastic — extremely light, durable materials that reduce the overall weight of the plane by as much as 20 percent compared to aluminum-bodied planes. Such lightweight airframes translate directly to fuel savings, which is a major point in advanced composites’ favor.

But composite materials are also surprisingly vulnerable: While aluminum can withstand relatively large impacts before cracking, the many layers in composites can break apart due to relatively small impacts — a drawback that is considered the material’s Achilles’ heel.

Now MIT aerospace engineers have found a way to bond composite layers in such a way that the resulting material is substantially stronger and more resistant to damage than other advanced composites. Their results are published this week in the journal Composites Science and Technology.

The researchers fastened the layers of composite materials together using carbon nanotubes — atom-thin rolls of carbon that, despite their microscopic stature, are incredibly strong. They embedded tiny “forests” of carbon nanotubes within a glue-like polymer matrix, then pressed the matrix between layers of carbon fiber composites. The nanotubes, resembling tiny, vertically-aligned stitches, worked themselves within the crevices of each composite layer, serving as a scaffold to hold the layers together.

In experiments to test the material’s strength, the team found that, compared with existing composite materials, the stitched composites were 30 percent stronger, withstanding greater forces before breaking apart.

Roberto Guzman, who led the work as an MIT postdoc in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro), says the improvement may lead to stronger, lighter airplane parts — particularly those that require nails or bolts, which can crack conventional composites.

“More work needs to be done, but we are really positive that this will lead to stronger, lighter planes,” says Guzman, who is now a researcher at the IMDEA Materials Institute, in Spain. “That means a lot of fuel saved, which is great for the environment and for our pockets.”

The study’s co-authors include AeroAstro professor Brian Wardle and researchers from the Swedish aerospace and defense company Saab AB.

“Size matters”

Today’s composite materials are composed of layers, or plies, of horizontal carbon fibers, held together by a polymer glue, which Wardle describes as “a very, very weak, problematic area.” Attempts to strengthen this glue region include Z-pinning and 3-D weaving — methods that involve pinning or weaving bundles of carbon fibers through composite layers, similar to pushing nails through plywood, or thread through fabric.

“A stitch or nail is thousands of times bigger than carbon fibers,” Wardle says. “So when you drive them through the composite, you break thousands of carbon fibers and damage the composite.”

Carbon nanotubes, by contrast, are about 10 nanometers in diameter — nearly a million times smaller than the carbon fibers.

“Size matters, because we’re able to put these nanotubes in without disturbing the larger carbon fibers, and that’s what maintains the composite’s strength,” Wardle says. “What helps us enhance strength is that carbon nanotubes have 1,000 times more surface area than carbon fibers, which lets them bond better with the polymer matrix.”

Stacking up the competition

Guzman and Wardle came up with a technique to integrate a scaffold of carbon nanotubes within the polymer glue. They first grew a forest of vertically-aligned carbon nanotubes, following a procedure that Wardle’s group previously developed. They then transferred the forest onto a sticky, uncured composite layer and repeated the process to generate a stack of 16 composite plies — a typical composite laminate makeup — with carbon nanotubes glued between each layer.

To test the material’s strength, the team performed a tension-bearing test — a standard test used to size aerospace parts — where the researchers put a bolt through a hole in the composite, then ripped it out. While existing composites typically break under such tension, the team found the stitched composites were stronger, able to withstand 30 percent more force before cracking.

The researchers also performed an open-hole compression test, applying force to squeeze the bolt hole shut. In that case, the stitched composite withstood 14 percent more force before breaking, compared to existing composites.

“The strength enhancements suggest this material will be more resistant to any type of damaging events or features,” Wardle says. “And since the majority of the newest planes are more than 50 percent composite by weight, improving these state-of-the art composites has very positive implications for aircraft structural performance.”

Stephen Tsai, emeritus professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University, says advanced composites are unmatched in their ability to reduce fuel costs, and therefore, airplane emissions.

“With their intrinsically light weight, there is nothing on the horizon that can compete with composite materials to reduce pollution for commercial and military aircraft,” says Tsai, who did not contribute to the study. But he says the aerospace industry has refrained from wider use of these materials, primarily because of a “lack of confidence in [the materials’] damage tolerance. The work by Professor Wardle addresses directly how damage tolerance can be improved, and thus how higher utilization of the intrinsically unmatched performance of composite materials can be realized.”

This work was supported by Airbus Group, Boeing, Embraer, Lockheed Martin, Saab AB, Spirit AeroSystems Inc., Textron Systems, ANSYS, Hexcel, and TohoTenax through MIT’s Nano-Engineered Composite aerospace STructures (NECST) Consortium and, in part, by the U.S. Army.

The problem with these new materials is not only direct-strength related. Fatigue of these materials is also of even greater significance. By sandwiching layers of aluminum alloy with fiber-glass, a Dutch firm managed to produce sheet materials whose fatigue resistance is much higher than regular aluminum. The name of this material is GLARE. This material is used in the pressure cabin fuselage of the Airbus 380 and presumably other Airbus products too(by now, its not so new). The problem with fatigue is due to stress concentrations around holes, and even today using this material the thickness of the joints is increased to make sure that the stress concentrations are no worse that when aluminum was not sandwiched. The excellent fatigue resistance of GLARE allows the doublers around holes and cut-outs to be eliminated, although I doubt if anyone has dared yet to design in this way. Even so weight savings are possible and have been achieved on AIRBUS 380.