A dramatic decline in the density of U.S. labor unions since the 1970s has resulted in lower wages for both union and nonunion workers, suggests a new study led by Jake Rosenfeld, associate professor of sociology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

The report, “Union decline lowers wages of nonunion workers: The overlooked reason why wages are stuck and inequality is growing,” was released Aug. 30 by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a Washington-based think tank funded in part by donations from labor unions.

“We’re talking about over $100 billion a year in lost wages,” Rosenfeld said in an interview with Marketplace public radio.

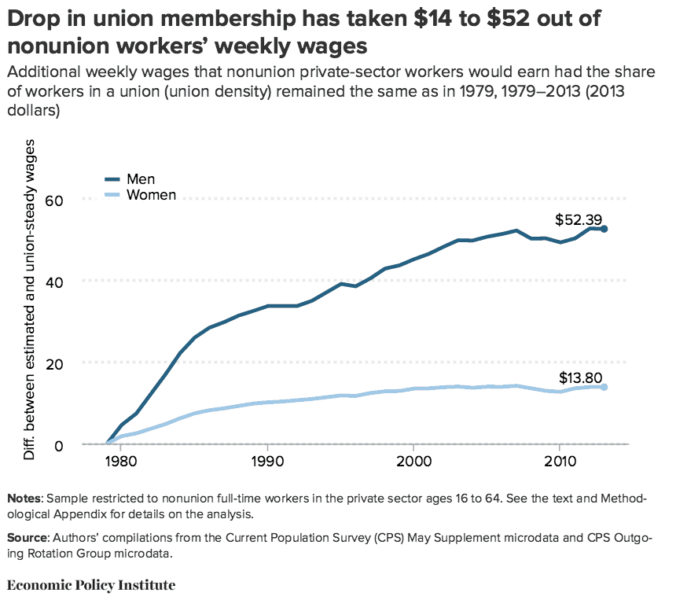

Rosenfeld and co-authors find that the dramatic decline in union density since 1979 has resulted in far lower wages for nonunion workers. Specifically, nonunion men lacking a college degree would have earned 8 percent, or $3,016 annually, more in 2013 if unions had remained as strong as they were in 1979.

“Working-class men have felt the decline in unionization the hardest,” said Rosenfeld. “Their paychecks are noticeably smaller than if unions had remained as strong as they were almost 40 years ago. Rebuilding collective bargaining is one of the tools we have to reinvigorate wage growth, for low- and middle-wage workers.”

Rosenfeld conducted the research with Patrick Denice, a postdoctoral research associate in sociology at Washington University, and Jennifer Laird, a postdoctoral research scientist with the Center on Poverty and Social Policy in the School of Social Work at Columbia University in New York.

Unions keep wages high for nonunion workers, they argue, because union agreements set wage standards and a strong union presence prompts managers to keep wages high in order to prevent workers from organizing or their employees from leaving. Unions also set industrywide norms, influencing what is seen as a “moral economy.”

Unions keep wages high for nonunion workers, they argue, because union agreements set wage standards and a strong union presence prompts managers to keep wages high in order to prevent workers from organizing or their employees from leaving. Unions also set industrywide norms, influencing what is seen as a “moral economy.”

Their analysis found that the share of private-sector workers in a union has fallen from about 34 percent to 11 percent among men, and from 16 percent to 6 percent among women, during a period spanning 1979- 2013.

Declining union participation has not had as dramatic an impact on the wages of nonunion women workers, they find, because women have not been as heavily represented in unionized private-sector jobs.

On the flip side, a rebound in collective bargaining would be expected to have as much or more impact on women as men. If unions had stayed at their 1979 levels, women’s wages would today be 2 to 3 percent higher, they estimate.

Their study also reveals that private-sector nonunion men of all education levels would earn 5 percent ($52) higher weekly wages in 2013 if private-sector union density (the share of workers in similar industries and regions who are union members) remained at its 1979 level, an increase of $2,704 in annual paychecks for full-time employees.

Looking broadly at how the four-decade decline in unions has eroded the wages for nonunion workers at every level of education and experience, the report estimates that weakened unions have cost full-time men and women working in the private sector as much as $133 billion in lost wages.

“Many American workers can see those unions as either minor bit players in today’s economy or good for union members alone to the detriment of society at large,” Rosenfeld told The Huffington Post. “This is a study that says that’s wrong: unions are good for members and nonmembers alike.”