Researchers at the University of Rochester have moved beyond the theoretical in demonstrating that an unbreakable encrypted message can be sent with a key that’s far shorter than the message — the first time that has ever been done.

Until now, unbreakable encrypted messages were transmitted via a system envisioned by American mathematician Claude Shannon, considered the “father of information theory.” Shannon combined his knowledge of algebra and electrical circuitry to come up with a binary system of transmitting messages that are secure, under three conditions: the key is random, used only once, and is at least as long as the message itself.

The findings by Daniel Lum, a graduate student in physics, and John Howell, a professor of physics, have been published in the journal Physical Review A.

“Daniel’s research amounts to an important step forward, not just for encryption, but for the field of quantum data locking,” said Howell.

Quantum data locking is a method of encryption advanced by Seth Lloyd, a professor of quantum information at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, that uses photons — the smallest particles associated with light — to carry a message. Quantum data locking was thought to have limitations for securely encrypting messages, but Lloyd figured out how to make additional assumptions — namely those involving the boundary between light and matter–to make it a more secure method of sending data. While a binary system allows for only an on or off position with each bit of information, photon waves can be altered in many more ways: the angle of tilt can be changed, the wavelength can be made longer or shorter, and the size of the amplitude can be modified. Since a photon has more variables — and there are fundamental uncertainties when it comes to quantum measurements — the quantum key for encrypting and deciphering a message can be shorter that the message itself.

Lloyd’s system remained theoretical until this year, when Lum and his team developed a device — a quantum enigma machine — that would put the theory into practice. The device takes its name from the encryption machine used by Germany during World War II, which employed a coding method that the British and Polish intelligence agencies were secretly able to crack.

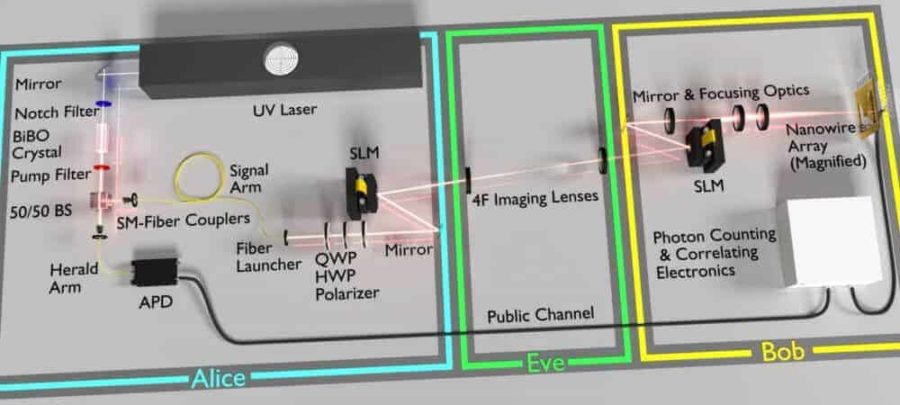

Let’s assume that Alice wants to send an encrypted message to Bob. She uses the machine to generate photons that travel through free space and into a spatial light modulator (SLM) that alters the properties of the individual photons (e.g. amplitude, tilt) to properly encode the message into flat but tilted wavefronts that can be focused to unique points dictated by the tilt. But the SLM does one more thing: it distorts the shapes of the photons into random patterns, such that the wavefront is no longer flat which means it no longer has a well-defined focus. Alice and Bob both know the keys which identify the implemented scrambling operations, so Bob is able to use his own SLM to flatten the wavefront, re-focus the photons, and translate the altered properties into the distinct elements of the message.

Let’s assume that Alice wants to send an encrypted message to Bob. She uses the machine to generate photons that travel through free space and into a spatial light modulator (SLM) that alters the properties of the individual photons (e.g. amplitude, tilt) to properly encode the message into flat but tilted wavefronts that can be focused to unique points dictated by the tilt. But the SLM does one more thing: it distorts the shapes of the photons into random patterns, such that the wavefront is no longer flat which means it no longer has a well-defined focus. Alice and Bob both know the keys which identify the implemented scrambling operations, so Bob is able to use his own SLM to flatten the wavefront, re-focus the photons, and translate the altered properties into the distinct elements of the message.

Along with modifying the shape of the photons, Lum and the team made use of the uncertainty principle, which states that the more we know about one property of a particle, the less we know about another of its properties. Because of that, the researchers were able to securely lock in six bits of classical information using only one bit of an encryption key–an operation called data locking.

“While our device is not 100 percent secure, due to photon loss,” said Lum, “it does show that data locking in message encryption is far more than a theory.”

The ultimate goal of the quantum enigma machine is to prevent a third party — for example, someone named Eve — from intercepting and deciphering the message. A crucial principle of quantum theory is that the mere act of measuring a quantum system changes the system. As a result, Eve has only one shot at obtaining and translating the encrypted message — something that is virtually impossible, given the nearly limitless number of patterns that exist for each photon.

The paper by Lum and Howell was one of two papers published simultaneously on the same topic. The other paper, “Quantum data locking,” was from a team led by Chinese physicist Jian-Wei Pan.

“It’s highly unlikely that our free-space implementation will be useful through atmospheric conditions,” said Lum. “Instead, we have identified the use of optic fiber as a more practical route for data locking, a path Pan’s group actually started with. Regardless, the field is still in its infancy with a great deal more research needed.”