As if you weren’t feeling this already, new research from Duke University says two motivations — your policy positions and your social identity — are competing to shape which candidate you will choose or whether you will vote at all.

Policy positions are a rational way to decide: pick a president whose policies align more closely with your own. Social identity, on the other hand, is what your vote means for your own self-image and how others see you.

Political science researchers have generated many theories about voter choice. Most of them assume voters choose rationally, while others acknowledge the role of identity. But none had proposed that rational choice and identity might actually compete to determine voter choice.

Decision-making research from the fields of neuroscience and social psychology provides the foundation for this new set of predictions, described Oct. 18 in the journal Trends in Cognitive Science.

“We think that treating identity as something that competes with policy helps explain why voters often select candidates whose policies go against their own interests,” said senior investigator Scott Huettel, chair of psychology and neuroscience at Duke.

Huettel and political science graduate student Libby Jenke are testing the predictions of their new model ahead of the November election.

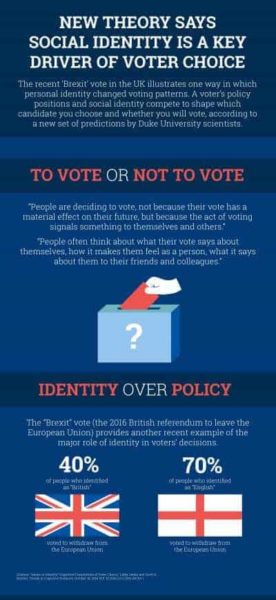

“People often think about what their vote says about themselves, how it makes them feel as a person, what it says about them to their friends and colleagues,” said Huettel, who is a member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

The group’s new model might explain some paradoxical voter choices in real-life examples, among them:

To vote or not to vote

For some people, the act of voting itself is primarily about identity — not about the direct personal benefits of a vote, Huettel said. The chance that an individual’s vote will have an impact on the presidential election is slim-to-none in most cases, because of the sheer number of people who vote and because of how the Electoral College system is set up.

But if you cringe after reading that fact, you’re not alone. The act of voting carries a strong sense of identity, which is reinforced by the social media streams we wade in on a daily basis.

“People are deciding to vote not because their vote has a material effect on their future, but because the act of voting signals something to themselves and others,” Huettel said.

This adds to a political science theory called “expressive voting,” which reasons that people have non-rational motives for voting. “In our model, we are specifying that these expressive votes are motivated by identity,” Jenke said.

For example, shortly after the presidential primaries, media outlets reported that Bernie Sanders supporters were having a difficult time shifting their support to Hillary Clinton when she became the Democratic nominee.

“What’s striking is that it’s extremely difficult for people to sacrifice their identification with their previous candidate — even when they recognize that one of the remaining candidates is closer to their personal interests than another,” Huettel said. “You can’t explain that with any traditional model.”

Identity Over Policy

The “Brexit” vote (the 2016 British referendum to leave the European Union) provides another recent example of the major role of identity in voters’ decisions. About 40 percent of people who identified as “British” voted to withdraw from the European Union, whereas 70 percent of those who identified themselves as “English” voted to withdraw.

“For many people, the vote to leave the European Union is a signal that you supported your country, you’re patriotic, you’re a nationalist,” Huettel said. But a different identity could reinforce a vote to stay, such as in those people who identify as being a European or a citizen of the world.

“We’re not saying that using identity in voting is wrong,” Jenke said. “Instead what we’re saying is that there are going to be cases in which people will vote against their own self-interest because identity has such a strong impact. In the short term, however, that vote says something about themselves that they find very rewarding.”

“We’re not saying that using identity in voting is wrong,” Jenke said. “Instead what we’re saying is that there are going to be cases in which people will vote against their own self-interest because identity has such a strong impact. In the short term, however, that vote says something about themselves that they find very rewarding.”

Party identification

Over the past few decades, party loyalty has increased. Yet, despite the apparent rise in severe partisanship, voters’ positions on policy issues have not become more polarized.

Huettel and Jenke say their new model may point to potential solutions for partisanship. Because political parties often attract voters more on the basis of social identity than policy, emphasizing the real policy differences between the major parties would weaken the effects of identity. Previous evidence suggests that when individuals are exposed to competing perspectives on questions of policy, people are less likely to vote in line with their party affiliation.