Although powerful people often tend to decide and act quickly, they become more indecisive than others when the decisions are toughest to make, a new study suggests.

Researchers found that when people who feel powerful also feel ambivalent about a decision – torn between two equally good or bad choices – they actually have a harder time taking action than people who feel less powerful.

That’s different than when powerful people are confronted by a simpler decision in which most evidence favors a clear choice. In those cases, they are more decisive and act more quickly than others.

“We found that ambivalence made everyone slower in making a decision, but it particularly affected people who felt powerful. They took the longest to act,” said Geoff Durso, lead author of the study and doctoral student in psychology at The Ohio State University.

The study was published online in the journal Psychological Science.

Richard Petty, co-author of the study and professor of psychology at Ohio State, said other research he and his colleagues have done suggests that feeling powerful gives people more confidence in their own thoughts.

That’s fine when you have a clear idea about the decision you want to make. But if you feel powerful and also ambivalent about a decision you face, that can make you feel even more conflicted than others would be, he said.

“If you think both your positive thoughts and your negative thoughts are right, you’re going to become frozen and take longer to make a decision,” Petty said.

The study involved two separate experiments that recruited college students as participants. They were told the goal of the experiments was to understand how people make decisions about employees based on limited information.

Each participant was given 10 behaviors attributed to an employee named Bob. Some were given a list of behaviors that were entirely positive or entirely negative, while others were given a list of five behaviors of Bob that were positive and five that were negative.

One of the negative behaviors was that Bob was caught stealing the mug of a co-worker when it was left in the company kitchen. A positive behavior was that Bob had met or beaten all but one of his earnings goals since he was hired.

After learning about Bob, participants were asked to write about a time in their lives when they had a lot of power or very little power over others. This writing exercise has been shown in other studies to induce momentary feelings of power or powerlessness among those who complete the task.

At this point, the researchers were able to start measuring how feelings of power interacted with feelings of ambivalence toward the employee.

Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they felt conflicted, undecided or mixed about their attitudes toward Bob – all measures of ambivalence. As expected, those who were told Bob showed a mixture of positive and negative behaviors felt much more ambivalent toward him than those who were told his behaviors were all positive or all negative.

They were then asked how likely it would be that they would delay making any decisions about Bob’s future with the company, if they were given such an opportunity.

When presented with an ambivalent profile for Bob, participants who felt powerful were more likely than others to want to delay the decision. But when the employee was presented as all-positive or all-negative, those who felt powerful were less likely than others to want to delay action.

After answering how much they wanted to delay the decision, the moment of truth came for the participants. In one study, they had to decide whether to promote Bob by clicking a key on a computer keyboard. In a second study, they decided whether to fire him the same way.

Without their knowledge, the researchers measured how long it took participants to click the key to promote or fire Bob.

Findings showed that, across the board, people took more time to decide when faced with the employee profile that mixed positive and negative behaviors. But those who were feeling powerful still took significantly longer to make their decision than did those who were feeling relatively powerless.

“Powerful people feel more confident than others in their own thoughts, they think their thoughts are more useful and more true. But that can be a problem if your thought is that you’re not really sure the best way to proceed,” Durso said.

“Meanwhile, people who feel less powerful are less sure about the validity of their thoughts anyway, so they think they might as well just make a decision.”

Durso and Petty believe this interaction between power and ambivalence can affect leaders in any role, including those in business and government.

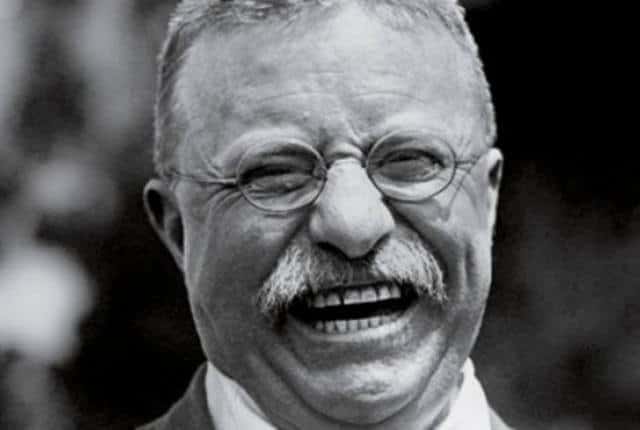

One example is President George W. Bush, who after his election in 2004 proclaimed that he was ready to take action: “I really didn’t come here [just] to hold the office…I came here to get some things done.”

But when determining whether to withdraw or bolster American forces in Iraq, President Bush — famously self-described as “the decider” — stated that he would “not be rushed into making a decision.” He then delayed his decision twice over two months.

This study suggests that Bush’s indecision was not surprising given his power as president and the complex, ambivalent issue he faced.

“People in power are given the most difficult decisions. They have a lot of conflicting information they have to process and synthesize to make their judgment,” Durso said.

“It is ironic that their feelings of power may actually make it more difficult for them to arrive at an answer than if they felt less powerful.”

The study was also co-authored by Pablo Briñol of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in Spain. The National Science Foundation provided support for the research.