A new study published today in Scientific Reports by University of Delaware researchers and colleagues reveals that 100 feet below the surface of the ocean is a critical depth for ecological activity in the Arctic polar night — a period of near continuous winter darkness.

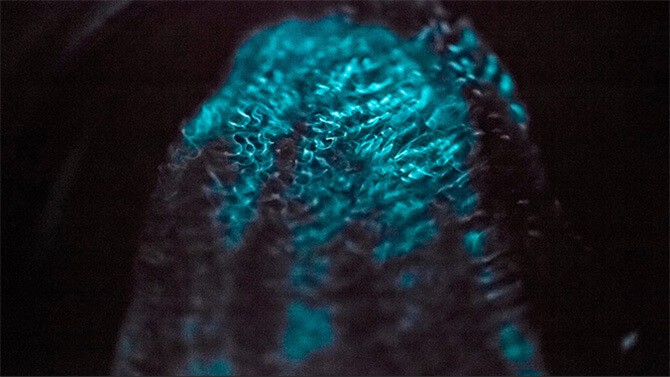

It is at this depth, the researchers said, that atmospheric light diminishes in the water column and bioluminescence from marine organisms becomes the dominant light source. It also is the site of significant changes in the composition of luminescent organisms present in the water column.

“It turns out that approximately 100 feet in depth is an important transition zone,” said Jonathan Cohen, a UD assistant professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment and co-author on the paper.

The research team has been studying how much biological activity takes place in the Arctic polar night since 2012, when UD’s Mark Moline, director of the School of Marine Science and Policy and colleagues in Norway and Scotland began exploring how sea life copes with continuous winter darkness in Svalbard, Norway. Prevailing scientific thought until then was that the food web remained dormant during the polar night.

The researchers said that bioluminescence can help explain how some organisms feed and maintain activity during the polar night period and how light can still be involved in ecological processes even during a time of darkness.

Taking roll call

One interesting finding in the current study is that as depth increased, the amount of bioluminescence in the water column increased and the zooplankton community composition changed.

“As you go deeper into the water, we saw fewer dinoflagellates and more copepods, krill and ctenophores, which give off brighter bioluminescent light,” said Cohen, who joined the research team in 2013.

This community change is not associated with any physical conditions of the water, the researchers said. Rather, it correlates to what the researchers term “bioluminescence compensation depth,” the transition point at which atmospheric light diminishes in the water column and bioluminescence takes over.

“This points to the functionality of bioluminescence structuring the vertical distribution through behavior possibly independent of migration,” said Moline.

This is an important finding as the Barents Sea south of Svalbard, Norway, is home to a large and globally important fishery. Fishermen in the region are tremendously interested in understanding how changes in zooplankton — like copepods — and zooplankton availability will affect commercially important fish species like cod and herring.

The researchers knew from other studies that the distribution of zooplankton and krill in the water column increased at around 100 feet.

“When the sky gets brighter at midday during the polar night period there is more atmospheric light available underwater for predation than at night, so marine organisms like copepods retreat lower into the water column where it is darker. We wanted to know how this light interacted with bioluminescence to influence life in the water column,” Cohen said.

The researchers first attacked this issue by taking atmospheric light measurements in 2014 and 2015, while also measuring bioluminescence in the water. This led to a more detailed study in 2015 of which planktonic species produced light. Finally, they put it all together to think about how bioluminescence can be a light source during the polar night.

Then UD graduate student Heather Cronin, working with Cohen and Moline, created what is called a photon budget, or light budget, to measure how much light comes from the atmosphere and how much light comes from inside the water itself with organisms glowing through bioluminescence.

To quantify the amount of bioluminescence and to identify what marine organisms were present, the researchers used a pumping system in the water column to drive the organisms into a specialized device equipped with a sensitive light meter.

As the organisms entered the device, turbulence created by the pump stimulated the animals to luminesce or glow. Using luminescence kinetics, or the time course of light production and dissipation, the researchers measured how the light intensity inside the pump changed with time in order to identify the marine species present.

“Luminescent marine organisms each have a unique light signature. By looking at the time series light generated by a flash within the instrument, we were able to determine who was there making the flash,” Cohen explained. “It’s a useful tool, particularly at this time of year when relatively few species are present.”

Bioluminescence is known to play a critical role in helping marine organisms avoid predators and even hide themselves in plain site. At the same time, Cohen continued, it appears that krill and potentially fish are using the additional bioluminescent light from the copepods to find food.

“We know from analysis of gut contents that fish and seabirds are active and feeding in Svalbard fjords during polar night,” Cohen explained. “Our research suggests that bioluminescent light may be one of the ways that they find food in the dark.”

Climate change connection

One looming concern under climate change scenarios is the loss of sea ice.

According to Cohen, scientists are just beginning to appreciate that climate change will change the light environment, which will impact the timing of the ice algae and phytoplankton blooms that spur the spring growing season, maybe even causing it to occur earlier in the year.

In the Arctic, for example, sea ice is part of what makes the water column dark. So, if the depth at which atmospheric light transitions to bioluminescent light is important in structuring the zooplankton community and the ecological interactions among organisms, then understanding how much atmospheric light will be present in the water column with less sea ice is significant for understanding food web dynamics.

The novelty in the team’s work is the focus on putting numbers and data to the processes that occur directly before the spring cycle begins. The next step is to make similar measurements further away from Svalbard to validate their findings in the open ocean.

“Being able to measure this transition depth gives us something to look at across seasons and across years that could have important implications for food web impacts in a rapidly changing Arctic,” Cohen said.

Co-authors on the paper include Heather Cronin (the paper’s lead author and former UD master’s student), Jonathan Cohen, Jørgen Berge (UiT The Arctic University of Norway and University Centre in Svalbard), Geir Johnsen (University Centre in Svalbard and Norwegian University of Science and Technology) and Mark Moline, director of the School of Marine Science and Policy at University of Delaware.