Leaders of authoritarian regimes in Central Asia have been able to use rhetoric to define their power as legitimate to the public despite practices of human rights violations and clamping down on dissent, according to a new study by a University of Kansas expert on international relations.

“Those governments have been fairly effective in mobilizing public support through discourse that has shaped the public’s understanding of what it means to have a legitimate government,” said Mariya Omelicheva, associate professor of political science. “They’ve persuaded the public that their ideas of legitimacy were informed by the countries’ histories and traditions. These governments presented their practices as consistent with the people’s primary demands and needs.”

Omelicheva in her study published recently in the Central Asian Survey journal analyzed a corpus of texts written or spoken between 1997 and 2015 by Kazakhstan’s president Nursultan Nazarbayev and Uzbekistan’s late president Islam Karimov, who died last September after 27 years in power.

The study is important, she said, because roughly 25 years after the breakup of the Soviet Union, several relatively stable authoritarian regimes have emerged in the region. They have adopted formal trappings of democracy, but they have made no progress as states in democratic transformation.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are also viewed as the two most important states in the region economically and politically.

“The leadership of these states have been determined to maintain power under the guise of democracy without exposing themselves to the political risks of competition,” Omelicheva said. “They have every single formal democratic institution, but they strip them of their democratic essence.”

For example, political platforms of the main parties are almost indistinguishable and aligned with the government’s positions. Various legal and political barriers effectively block the rise of opposition. The competitors in presidential elections publicly give their vote to incumbent presidents.

“Because of these obvious infractions on democratic principles in practice, these authoritarian governments generate public support by resorting to performance legitimation, meaning they would assert that they have been effective in delivering on the public’s demands for order, stability, security and socioeconomic progress,” Omelicheva said.

More or less they have been successful in following up on their promises relative to the terms they’ve defined, she said.

Omelicheva found that Nazarbayev and Karimov both used similar rhetorical tactics by comparing their countries’ economies at the dawn of their independence — the collapse of the Soviet Union — to the present day, arguing how much progress they have made.

Understanding how authoritarian regimes construct and sell their legitimacy can help international players attune their foreign policy approaches and expectations with regards to these states’ democratization and economic liberalization.

Also, she said the research has broader implications in understanding the rhetorical strategies used by politicians anywhere to engender public support for their own rule and to delegitimize the rule of their opponents. Donald Trump’s surprising victory in this month’s U.S. presidential election came on the heels of his constant lambasting of the system in Washington and promises to improve the economic situation, particularly for people in states that have suffered from losses of manufacturing and blue-collar jobs.

“He rose on appeals to poor performance of the current government and the establishment as a whole, thus denying them the so-called performance legitimation,” she said.

In a democracy, it will be key to see how the public views Trump’s performance as president and whether he not only seeks to accurately follow through on promises he made but how other branches of government — as part of a system of checks and balances of power — and the media interact with his administration and hold him accountable, if not, she said.

“Words matter. The power of persuasion and manipulation matters,” Omelicheva said. “We need to take rhetoric seriously, even if we know — in the case of authoritarian regimes — that the rhetoric is manipulative.”

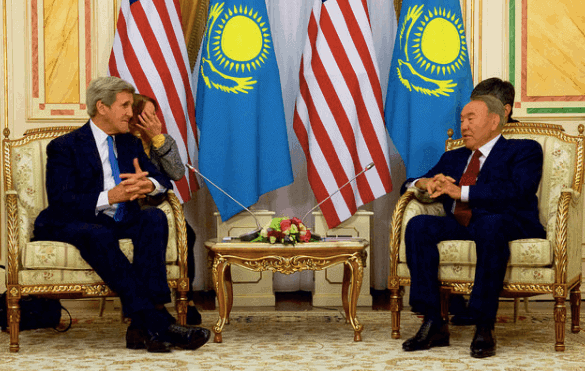

Photo: U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry speaks with President Nursultan Nazarbayev while meeting in the Gold Room at Ak Orda Presidential Palace in Astana, Kazakhstan. Image from the State Department.