A molecule found in car engine exhaust fumes that is thought to have contributed to the origin of life on Earth has made astronomers heavily underestimate the amount of stars that were forming in the early Universe, a University of California, Riverside-led study has found.

That molecule is called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH). On Earth it is also found in coal and tar. In space, it is a component of dust, which along with gas, fills the space between stars within galaxies.

The study, which was just published in the Astrophysical Journal, represents the first time that astronomers have been able to measure variations of PAH emissions in distant galaxies with different properties. It has important implications for the studies of distant galaxies because absorption and emission of energy by dust particles can change astronomers’ views of distant galaxies.

“Despite the ubiquity of PAHs in space, observing them in distant galaxies has been a challenging task,” said Irene Shivaei, a graduate student at UC Riverside, and leader of the study. “A significant part of our knowledge of the properties and amounts of PAHs in other galaxies is limited to the nearby universe.”

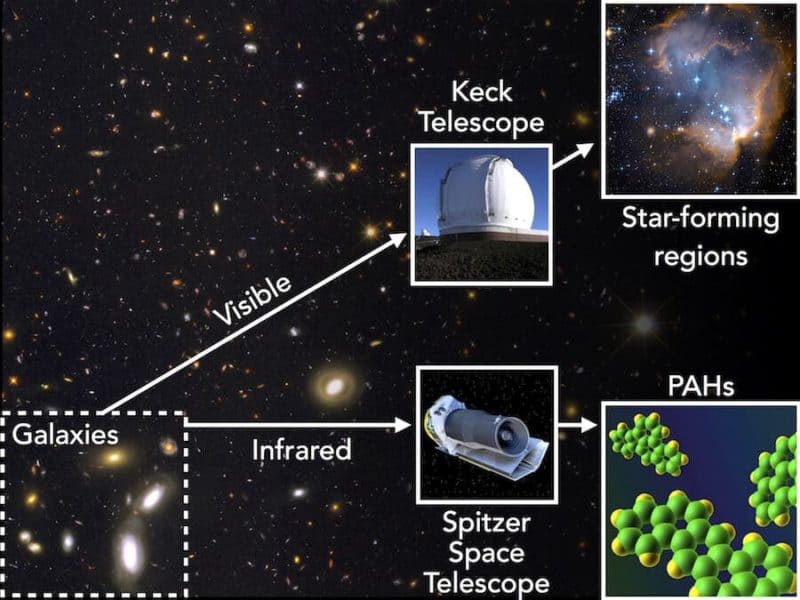

The research was conducted as part of the University of California-based MOSDEF survey, a study that uses the Keck telescope in Hawaii to observe the content of about 1,500 galaxies when the universe was 1.5 to 4.5 billion years old. The researchers observed the emitted visible-light spectra of a large and representative sample of galaxies during the peak-era of star formation activity in the universe.

In addition, the researchers incorporated infrared imaging data from the NASA Spitzer Space Telescope and the European Space Agency-operated Herschel Space Observatory to trace the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emission in mid-infrared bands and the thermal dust emission in far-infrared wavelengths.

The researchers concluded that the emission of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules is suppressed in low-mass galaxies, which also have a lower fraction of metals, which are atoms heavier than hydrogen and helium. These results indicate that the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules are likely to be destroyed in the hostile environment of low-mass and metal-poor galaxies with intense radiation.

The researchers also found that the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emission is relatively weaker in young galaxies compared to older ones, which may be due to the fact that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules are not produced in large quantities in young galaxies.

They found that the star-formation activity and infrared luminosity in the universe 10 billion years ago is approximately 30 percent higher than previously measured.

Studying the properties of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mid-infrared emission bands in distant universe is of fundamental importance to improving our understanding of the evolution of dust and chemical enrichment in galaxies throughout cosmic time. The planned launch of the James Webb Space Telescope in 2018 will push the boundaries of our knowledge on dust and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in the early universe.

The Astrophysical Journal paper is called “The MOSDEF Survey: Metallicity Dependence of PAH Emission at High Redshift and Implications for 24 μm Inferred IR Luminosities and Star Formation Rates at z ∼ 2.”

In addition to Shivaei, the authors are: Naveen Reddy, Brian Siana, and Bahram Mobasher, of UC Riverside; Alice Shapley and Ryan L. Sanders, of UCLA; Mariska Kriek, Sedona H. Price, and Tom Zick, of UC Berkeley; and Alison L. Coil and Mojegan Azadi, of UC San Diego.