Material scientists have predicted and built two new magnetic materials, atom-by-atom, using high-throughput computational models. The success marks a new era for the large-scale design of new magnetic materials at unprecedented speed.

Although magnets abound in everyday life, they are actually rarities — only about five percent of known inorganic compounds show even a hint of magnetism. And of those, just a few dozen are useful in real-world applications because of variability in properties such as effective temperature range and magnetic permanence.

The relative scarcity of these materials can make them expensive or difficult to obtain, leading many to search for new options given how important magnets are in applications ranging from motors to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines. The traditional process involves little more than trial and error, as researchers produce different molecular structures in hopes of finding one with magnetic properties. Many high-performance magnets, however, are singular oddities among physical and chemical trends that defy intuition.

In a new study, materials scientists from Duke University provide a shortcut in this process. They show the capability to predict magnetism in new materials through computer models that can screen hundreds of thousands of candidates in short order. And, to prove it works, they’ve created two magnetic materials that have never been seen before.

The results appear April 14, 2017, in Science Advances.

“Predicting magnets is a heck of a job and their discovery is very rare,” said Stefano Curtarolo, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and director of the Center for Materials Genomics at Duke. “Even with our screening process, it took years of work to synthesize our predictions. We hope others will use this approach to create magnets for use in a wide range of applications.”

The group focused on a family of materials called Heusler alloys — materials made with atoms from three different elements arranged in one of three distinct structures. Considering all the possible combinations and arrangements available using 55 elements, the researchers had 236,115 potential prototypes to choose from.

To narrow the list down, the researchers built each prototype atom-by-atom in a computational model. By calculating how the atoms would likely interact and the energy each structure would require, the list dwindled to 35,602 potentially stable compounds.

From there, the researchers conducted a more stringent test of stability. Generally speaking, materials stabilize into the arrangement requiring the least amount of energy to maintain. By checking each compound against other atomic arrangements and throwing out those that would be beat out by their competition, the list shrank to 248.

Of those 248, only 22 materials showed a calculated magnetic moment. The final cut dropped any materials with competing alternative structures too close for comfort, leaving a final 14 candidates to bring from theoretical model into the real world.

But as most things in a laboratory turn out, synthesizing new materials is easier said than done.

“It can take years to realize a way to create a new material in a lab,” said Corey Oses, a doctoral student in Curtarolo’s laboratory and second author on the paper. “There can be all types of constraints or special conditions that are required for a material to stabilize. But choosing from 14 is a lot better than 200,000.”

For the synthesis, Curtarolo and Oses turned to Stefano Sanvito, professor of physics at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland. After years of attempting to create four of the materials, Sanvito succeeded with two.

Both were, as predicted, magnetic.

The first newly minted magnetic material was made of cobalt, magnesium and titanium (Co2MnTi). By comparing the measured properties of similarly structured magnets, the researchers were able to predict the new magnet’s properties with a high degree of accuracy. Of particular note, they predicted the temperature at which the new material lost its magnetism to be 940 K (1232 degrees Fahrenheit). In testing, the actual “Curie temperature” turned out to be 938 K (1228 degrees Fahrenheit) — an exceptionally high number. This, along with its lack of rare earth elements, makes it potentially useful in many commercial applications.

“Many high-performance permanent magnets contain rare earth elements,” said Oses. “And rare earth materials can be expensive and difficult to acquire, particularly those that can only be found in Africa and China. The search for magnets free of rare-earth materials is critical, especially as the world seems to be shying away from globalization.”

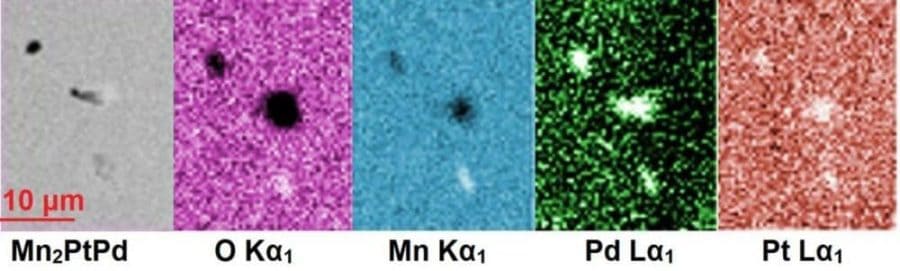

The second material was a mixture of manganese, platinum and palladium (Mn2PtPd), which turned out to be an antiferromagnet, meaning that its electrons are evenly divided in their alignments. This leads the material to have no internal magnetic moment of its own, but makes its electrons responsive to external magnetic fields.

While this property doesn’t have many applications outside of magnetic field sensing, hard drives and Random Access Memory (RAM), these types of magnets are extremely difficult to predict. Nevertheless, the group’s calculations for its various properties remained spot on.

“It doesn’t really matter if either of these new magnets proves useful in the future,” said Curtarolo. “The ability to rapidly predict their existence is a major coup and will be invaluable to materials scientists moving forward.”