Hyper-connectivity has changed the way we communicate, wait, and productively use our time. Even in a world of 5G wireless and “instant” messaging, there are countless moments throughout the day when we’re waiting for messages, texts and Snapchats to refresh. But our frustrations with waiting a few extra seconds for our emails to push through doesn’t mean we have to simply stand by.

To help us make the most of these “micro-moments,” researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have developed a series of apps called “WaitSuite” that test you on vocabulary words during idle moments, like when you’re waiting for an instant message or for your phone to connect to WiFi.

Building on micro-learning apps like Duolingo, WaitSuite aims to leverage moments when a person wouldn’t otherwise be doing anything – a practice that its developers call “wait-learning.”

“With stand-alone apps, it can be inconvenient to have to separately open them up to do a learning task,” says PhD student Carrie Cai, who leads the project. “WaitSuite is embedded directly into your existing tasks, so that you can easily learn without leaving what you were already doing.”

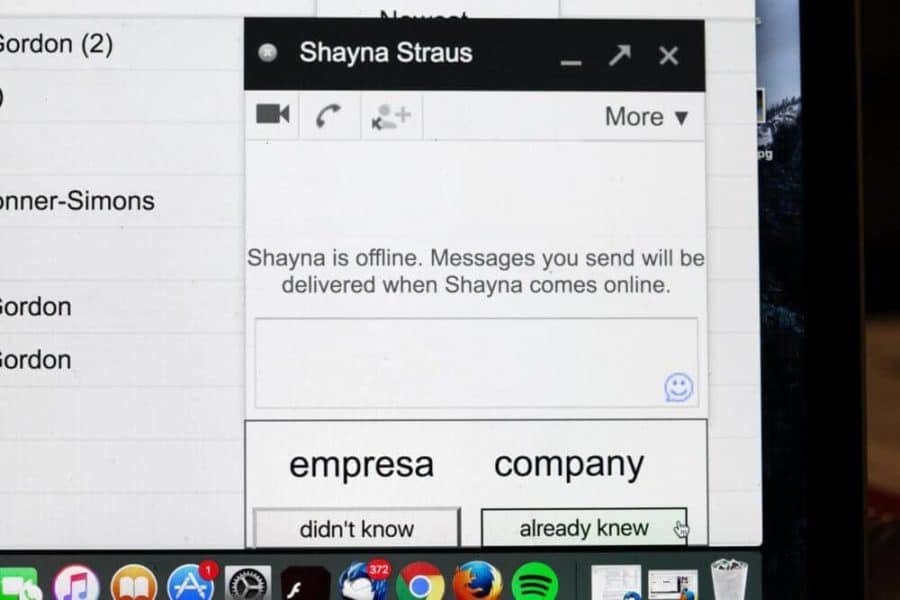

WaitSuite covers five common daily tasks: waiting for WiFi to connect, emails to push through, instant messages to be received, an elevator to come, or content on your phone to load. When using the system’s instant messaging app “WaitChatter,” users learned about four new words per day, or 57 words over just two weeks.

Ironically, Cai found that the system actually enabled users to better focus on their primary tasks, since they were less likely to check social media or otherwise leave their app.

WaitSuite was developed in collaboration with MIT professor Rob Miller and former MIT student Anji Ren. A paper on the system will be presented at ACM’s CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems this coming May in Colorado.

Among WaitSuite’s apps include “WiFiLearner,” which gives users a learning prompt when it detects that their computer is seeking a WiFi connection. Meanwhile, “ElevatorLearner” automatically detects when a person is near an elevator by sensing Bluetooth iBeacons, and then sends users a vocabulary word to translate.

Though the team used WaitSuite to teach vocabulary, Cai says that it could also be used for learning things like math, medical terms or legal jargon.

“The vast majority of people made use of multiple kinds of waiting within WaitSuite,” says Cai. “By enabling wait-learning during diverse waiting scenarios, WaitSuite gave people more opportunities to learn and practice vocabulary words.”

Still, some types of waiting were more effective than others, making the “switch time” a key factor. For example, users liked that with “ElevatorLearner,” wait time was typically 50 seconds and opening the flashcard app took ten seconds, leaving free leftover time. For others, doing a flashcard while waiting for WiFi didn’t seem worth it if the WiFi connected quickly, but those with slow WiFi felt that doing a flashcard made waiting less frustrating.

In the future, the team hopes to test other formats for micro-learning, like audio for on-the-go users. They even picture having the app remind users to practice mindfulness to avoid reaching for our phones in moments of impatience, boredom, or frustration.

“This work is really interesting because it looks to help people make use of all the small bits of wasted time they have every day” says Jaime Teevan, a principal researcher at Microsoft who was not involved in the paper. “I also like how it takes into account a person’s state of mind by, for example, giving terms to learn that relate to the conversations they are having.”