For centuries eyes have been considered “windows to the soul,” their expressions looked upon intuitively as clues to the emotional state of the beholder. New research by CU Boulder scientist Daniel Lee suggests those widened or squinted eyes (and the raised or furrowed brows that often come with them) originated as much more than social cues.

Researcher Daniel Lee has been studying facial expressions for eight years.

In fact, they probably helped the human race survive.

“We know that our eyes are extremely important for social signaling, but to understand why that is you have to go back to Darwin’s theories,” says Daniel Lee, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Cognitive Science who has been studying facial expressions for eight years. “Our research suggests these expressions evolved for functional reasons first – to help the expresser gather more information and enhance his or her chances for survival – and were later co-opted as communication tools.”

Lee’s latest paper, published in the journal Psychological Science in February, examined precisely which eye features people use as they try to decode whether someone is fearful or disgusted, angry or surprised and how that decoding system came to be.

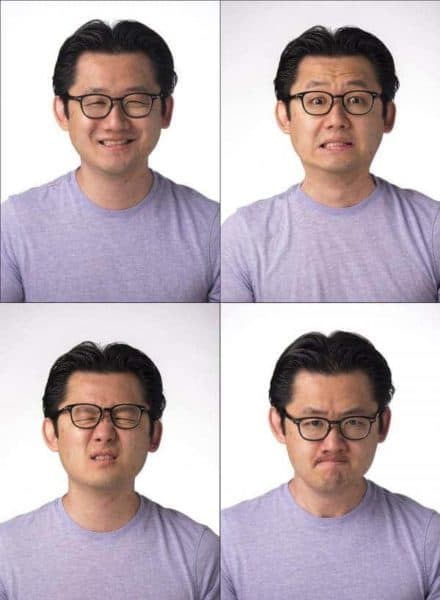

He and co-author Adam Anderson, a professor of neuroscience at Cornell’s College of Human Ecology, created images of six composite eye expressions (sadness, disgust, anger, joy, fear and surprise) created from ethnically diverse databases of faces. For each image, the researchers measured seven features: eye openness (distance from top to bottom of eye), eyebrow distance, eyebrow slope, eyebrow curvature, nasal wrinkles, wrinkles near the temples and wrinkles below the eyes.

Subjects were then shown the images on a computer screen, along with the name of one of the six basic emotions or 44 more complex ones (awe, cowardice, hate, suspicion, love) and asked to rank whether the eyes matched the emotion. Each participant completed 600 trials.

When looking at the eyes alone, the subjects got the emotion right about 90 percent of the time. Even when the lower face was shown making an incongruous expression, the subjects still got it right most of the time.

“When looking at the face, the eyes dominate emotional communication,” Anderson concludes.

Using the participants answers, the researchers then used computer modeling to develop a “mental state map” unraveling precisely which eye features were associated with which emotions.

Sixty-seven percent of the time the openness of the eye was a primary sign of emotion, with wide eyes signaling fear, surprise, awe and squinted eyes signaling opposite sentiments such as disgust, anger, and hate.

“We found that the most important dimension for reading the eyes is how wide open they are or how narrow they are,” Lee said.

Eye-narrowing was associated with a cluster of mental states that convey social discrimination, such as hate, suspicion, aggressiveness and contempt. Eye widening features were aligned with mental states that convey sensitivity, like awe, cowardice and interest.

From an evolutionary perspective, there’s a good reason for that.

The facial expressions map shows the relationship between mental states and eye features, with fear and surprise associated with wide eyes while disgust and anger are associated with narrowed eyes. States close to each other on the map are more likely to be confused with one another.

Previous research by Anderson and Lee showed that when subjects demonstrated a look of fear, with eyes open and brow raised, they became more sensitive to light, just like when a camera lens aperture opens. This could be useful for detecting predators. In contrast, when they expressed disgust, with eyes squinting and nose wrinkled, their vision became sharper, just like when narrowing a camera lens aperture – useful for a hunter examining a piece of suspect meat before deciding whether to eat it. (Their prior research also suggests lip curls and nose wrinkles, also associated with disgust, narrowed nasal passages, blocking smell).

Today, we still squint when we’re suspicious and grow wide-eyed when we’re surprised, and those observing us still make those associations.

The study also found that temporal wrinkles were associated with joy while curved eyebrows were associated with sadness.

“Emotional expressive changes around the eye influence how we see, and in turn, this communicates to others how we think and feel,” Anderson says.

Lee imagines that someday their work could help people with autism or others with difficulty reading emotional cues.

In the meantime, it lends scientific proof to a century-old suspicion.

“We have had this idea going back to Darwin that our expressions are not just arbitrary symbols, that there is a reason you can go to another country and make the expressions you make and have people respond to you in a predictable manner,” Lee says, noting that in all, people could make about 3.7 x 1016 different facial expressions. “To be able to do that accurately would be statistically impossible if there were not some sort of common evolutionary origin. Our research gets at that origin.”