In the constant evolutionary battle between predator and prey, one seemingly winning strategy is to get bigger over time so you can throw your weight around.

Paleontologists from UC Berkeley, the Florida Museum of Natural History and the University of Missouri have come up with perhaps the best example of this: the 500-million-year battle between marine predators such as snails and the animals whose shells they drilled through in order to suck out their innards.

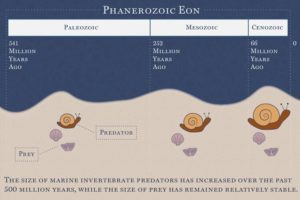

Over this period, predatory drillers — most likely snails — grew substantially larger, while their prey — clams, other snails and lamp shells — remained about the same size. This surprising finding, reported this week in the journal Science, is likely the result of many changes in the driller and drillee populations in the ocean over eons, but confirms the general rule for predators: Bigger is better.

“For predators, there can be a large advantage to being powerful, not necessarily efficient; to being able to hoover up a lot of small mollusks and get lots of energy to move around more quickly and avoid other predators,” said co-author Seth Finnegan, a UC Berkeley assistant professor of integrative biology. “What’s very exciting about this study is its ability to put together hundreds of millions of years of individual predator-prey interactions and see such a strong trend.”

The data comes from something very common in the fossil record: preserved shells with holes in them caused by drillers, such as the predatory murex and moon snails that prey on clams today, and whose shells are collector’s items.

Lead author Adiel Klompmaker, a UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow and a former postdoc at the Florida Museum, established that in today’s oceans, larger predators make larger drill holes, and used this as an indication of the size of predators in the distant past based on drill hole size in fossil shells. The team found that the percent of shell area drilled by predators increased 67-fold over the past 500 million years, suggesting that the ratio of predatory driller size and tough-shelled prey increased substantially.

“Drill holes increase in size while the size of the prey shell did not change,” said Klompmaker, who conducted most of the research. “This means that predators became bigger but prey remained the same size. Why so? Over geological time, prey contained more meat per shell and also became more abundant. Predators might have ingested more and more meat in a given period and thus became larger.”

Despite growing bigger, predators may not have needed to switch to larger targets because prey also became more nutritious through time, the researchers said. In the Paleozoic Era, about 541 million to 252 million years ago, clam-like organisms known as lamp shells or brachiopods were the most common prey available. But predators gained few nutrients from brachiopods and gradually transitioned to mollusks, similarly sized but meatier prey that became abundant in oceans after the Paleozoic.

“Attacking larger prey items is generally more dangerous, so why not focus on similar-sized yet more nutritious and more abundant prey?” Klompmaker said.

As predation ramped up, however, predators themselves were increasingly vulnerable to their own predators. Chasing, hunting and drilling into prey creates a window of time when predators are exposed to their own enemies, such as crabs and fish. Pursuing small, easy prey could lessen the risk to predators themselves.

“This project gives us the first glimpse into how the size of predators and prey are related to each other and how this size relation changed through the history of life,” said Michal Kowalewski, the Jon L. and Beverly A. Thompson Chair of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida and a study co-author.