Long before symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease become apparent to patients and their families, biological changes are occurring within the brain.

A new study led by Keck Medicine of USC neuropsychologist Duke Han, associate professor of family medicine (clinical scholar) at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, suggests that cognitive tests can detect early Alzheimer’s in people without symptoms.

“In the last decade or so, there has been a lot of work on biomarkers for early Alzheimer’s disease,” Han said. “There are new imaging methods that can identify neuropathological brain changes that happen early on in the course of the disease. The problem is that they are not widely available, can be invasive and are incredibly expensive. I wanted to see whether the cognitive tests I regularly use as a neuropsychologist relate to these biomarkers.”

Putting neuropsychological measures to the test

Han and his colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 61 studies to explore whether neuropsychological tests can identify early Alzheimer’s disease in adults over 50 with normal cognition.

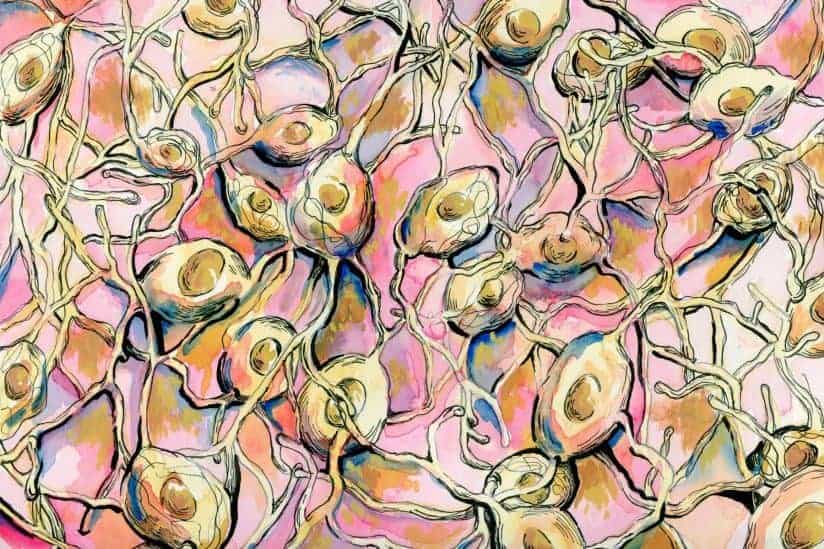

The study, published in Neuropsychology Review, found that people who had amyloid plaques — clusters of protein fragments that form in the brain and grow in number, eventually getting in the way of the brain’s ability to function — performed worse on neuropsychological tests of global cognitive function, memory, language, visuospatial ability, processing speed and attention/working memory/executive function than people who did not have amyloid plaques.

The study also found that people with neurodegeneration performed worse on memory tests than people with amyloid plaques.

“The presumption has been that there would be no perceivable difference in how people with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease perform on cognitive tests,” Han said. “This study contradicts that presumption.”

Routine cognitive screenings: A new normal?

Han believes that the study results provide a solid argument for incorporating cognitive testing into routine, annual checkups for older people.

“Having a baseline measure of cognition before noticing any kind of cognitive change or decline could be incredibly helpful because it’s hard to diagnose early Alzheimer’s disease if you don’t have a frame of reference to compare to,” Han said. “If people would consider getting a baseline evaluation by a qualified neuropsychologist at age 50 or 60, then it could be used as a way to track whether someone is experiencing a true decline in cognition in the future.”

An estimated 5 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s and that number could reach 16 million by 2050, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Early detection could be a powerful tool to manage it, Han said, giving people precious time to try different medications or interventions that may slow the progression of the disease early on.

“While there’s no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, the earlier you know that you’re at risk for developing it, the more you can potentially do to help stave off that diagnosis in the future,” Han said. “For example, exercise, cognitive activity and social activity have been shown to improve brain health.”