In most crime scenes, there is some information that is known only by investigators and the actual perpetrator. Only the kidnapper knows what the abandoned shed where they kept a victim looks like, and only the true thief will know which house was burglarized. When confronted by investigators about this type of information, suspects uniformly answer: “I’ve never seen that before.” Soon, however, neuroscience technology may be able to help the legal system differentiate the truth tellers from the liars, according to a University of Minnesota study.

The report, “The Limited Effect of Electroencephalography Memory Recognition Evidence on Assessments of Defendant Credibility,” published in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences, finds that brain-based memory recognition technology may be one step closer to court. The findings suggest American jurors can appropriately integrate the evidence in their evaluations of criminal defendants, which could ultimately lead to an additional expert witness on the stand.

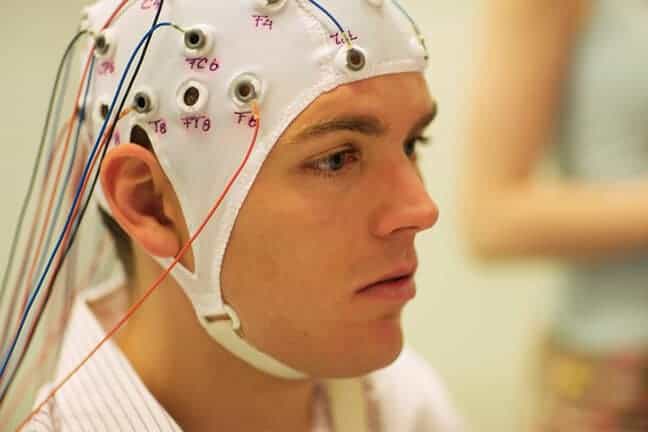

“The technology measures the electrical brain activity of defendants and witnesses, and should improve the legal system’s ability to determine who is telling the truth and who is not,” said Law Professor Francis Shen, the study’s lead author and director of the Neurolaw Lab, a unique collaborative at the University exploring the legal implications of neuroscience. “Our new interdisciplinary research is exciting because it’s some of the first to empirically test how this would work in practice.”

Assessing the credibility of human memory is a central feature of the criminal justice system, from early stages of investigations to courtroom adjudication. For more than two decades, scientists and legal scholars have observed that brain-based memory recognition technology might have the potential to improve the justice system.

The study includes results from multiple experiments examining the effect of neuroscientific evidence on subjects’ evaluation of a fictional criminal fact pattern, while manipulating the strength of the non-neuroscientific evidence. In two experiments, one using 868 online subjects and one using 611 in-person subjects, researchers asked subjects to read two short, fictional vignettes describing a protagonist accused of a crime.

Manipulating expert evidence and the strength of the non-neuroscientific facts against the defendant, it was discovered that the neuroscientific evidence was not as powerful a predictor as the overall strength of the case in determining outcomes. The study concluded that subjects are cognizant of, but not seduced by, brain-based memory recognition evidence.

“One day, it could become commonplace in justice investigations,” Shen said. “However, we need more studies like this and more collaboration across disciplines before we can be confident that this type of evidence should be used in real legal cases.”

Additional information about related research is available at Professor Shen’s website.